Introduction

Since

the initial clay tablet fragments were first translated in 1914, the Sumerian

“Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld” (hereafter referred to as ID) myth has

captured the attention and imagination of scholars, students, and the general

public.

While the more recent Assyrian account of “The Descent of Ishtar” is dated to

ca. 1100 BCE, scholars have agreed that the Sumerian version is older.[3]

ID is almost one thousand years older based on current date estimates of

related artifacts—that is, it is loosely dated as belonging to the Old

Babylonian period (ca. 1900 – 1600 BCE).[4]

It is difficult to know the exact time period and origin of the myth because of

how the related artifacts were discovered and processed by scholars,

governments, and curators over its four thousand-plus year history. The most

authoritative version of ID was published in 2001 by the contributors to the

Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (hereafter referred to as the

ETCSL version), a collaborative project by the University of Oxford and other

institutions.[5]

While many prominent scholars have published other translations, the present

survey will use the ETCSL version as its focus. As we will see, the ETCSL

version relied on efforts from dozens of scholars and almost fifty separate

artifacts in order to compile the total 412 lines of translated text it has

today.[6]

ID

can be briefly summarized as follows. Inanna, the Sumerian deity, sets her mind

on going to the netherworld and abandons various cities that are represented by

other deities. She takes with her the seven divine powers (the “me”), as

represented by articles of clothing, jewelry, makeup, and objects. Her travel

companion, Nincubura, accompanies her during the journey. Inanna gives precise

instructions to her companion to plead on her behalf if she does not return

within three days. Upon reaching the netherworld, she informs the

gatekeeper—Neti—that she has come to observe the funeral rites for her sister’s

husband, Gugulana. Neti proceeds to ask Ereshkigal, who is Inanna’s sister (and

the ruler of the netherworld), whether Inanna can come in. Ereshkigal instructs

Neti to allow Inanna to enter and Inanna proceeds through seven gates. At each

gate, one item she brought (including her clothing) is removed until she is

naked. Upon reaching the throne, she is seemingly killed, and her corpse is

hung on a metal hook. After three days, Nincubura follows the instructions

provided and travels to various temples to plead for Inanna’s life. In agreeing

to help Inanna, the god Enki devises a plan to bring her back to life and is

successful. As Inanna ascends back up from the netherworld, she is accompanied

by two demon-like figures that insist on bringing a different person back in

her place. Inanna discovers her husband, Dumuzi, and offers him in her place,

ending the poem.

Modern Relevance

The

plot summary of ID may provide us with one of the earliest recorded

descriptions of the afterlife. While the difficulty of proper dating methods

cannot be stressed enough, scholars can generally attribute time periods based

on the Sumerian language that was used and the location of the cities that were

referenced. Whatever the exact origin date of ID was, scholars recognize that

ancient Sumer was one of the earliest civilizations on our planet. Their

initial writing system, called cuneiform, was thus a means toward some of the

world’s first pieces of literature. We can reasonably deduce that writing in

the Sumerian language constitutes some of the earliest literary works of mankind—the

gravity of this statement needs no further explanation as to its importance for

historians studying death in the ancient world.

Inanna,

ID, and mythology have attracted interest from other disciplines as well as

mainstream culture. Within psychology, feminist theory interpretations have

been made of ID and used in clinical counseling settings for therapy.[7]

For many years, sociologists have used ancient history as a window to peer

through to see why and how society is the way it is today. A modest number of

general Sumerian references are made in the Judeo-Christian Bible,[8]

with scholars like Joseph Reider and others speculating that Ishtar was a

consistent mention in the Hebrew texts.[9]

The growing field of psychohistory is also anxiously awaiting newly translated

literary texts in order to assess the mentality of authors, listeners, and

characters, particularly as they relate to power relations between men and

women in antiquity.[10]

While the present survey cannot pass judgment or offer analysis on the validity

of these interpretations or uses, it is clear that there is interdisciplinary

interest in the Sumerian deity named Inanna, later known as Ishtar.

Mythology,

and particularly ID, have also made their way into mainstream culture,

sometimes without any reference to formal scholarship whatever. For example,

Inanna and her myth are readily utilized in the context of modern cultural

issues like gender identity and women’s rights. Evidence of this is present in

undergraduate scholarship[11]

as well as more public friendly news websites, among others.[12]

Within the sphere of cinema, too, we time and time again see the subtle

influence of ancient mythology—that is, behind the veil of special effects, fun

music, and action-filled plots are the literary remains of cultures that have

been long forgotten. As of the writing of this paragraph, the most popular

movie in America is Avengers: Endgame, featuring an archvillain named

Thanos who kills half the universe.[13]

Thanos, an oddly similar name to Thanatos

(Θάνατος), the Greek deity associated with

death and dying, is another example of modern cinema perhaps leaning on

mythology.[14]

The entirety of the current paragraph intentionally digressed from

authoritative scholarly references (with admittedly cherry-picked straw man

examples without peer review) to illustrate a broader cultural trend that is

most apparent. There is no question about the interdisciplinary interest and

modern sociocultural importance of mythology like ID—especially for the general

public.

Addressing the Needs of a Broader

Audience

A

major problem the present survey will hopefully address is the steep learning

curve the public and other scholars face when trying to investigate scholarship

related to ID. In considering the intimidating list of cuneiform artifacts

(sources, sometimes called witnesses) used for ID in the ETCSL version, we can

only imagine how a less trained scholar or reader may feel. Upon inspecting the

fifty listed artifacts,

one is immediately arrested by the sheer complexity of the acronyms,

publication annotation schemes, outdated resources, and jargon (like sigla).[16]

To make sense of a single artifact, say CBS 9800, for example, one must possess

at least basic proprietary technical knowledge in archaeology, linguistics,

Sumerian studies, cuneiform studies, and several other fields. Just locating

and assigning artifacts to translations and using the tools and websites

available are daunting—headache envelops the reader like a garment. Even with

having the necessary technical skills, readers are likely unprepared for the

further complexities related to prior scholarship, dissociated cultural timelines,

and other inherent obscurities present within any domain of ancient studies.

The

primary purpose of this survey is to belatedly pay tribute to a century of

scholarship on ID by organizing the accomplishments for a broader audience.

Most of the scholars who contributed many years of their lives to ID are no

longer with us. The present work will attempt to organize their contributions

systematically and chronologically for a reader who is wholly unfamiliar with

the material but wishes to engage more rigorously. My humble contribution is,

therefore, solely as a compiler of such efforts—that is, I have excluded

my own interpretations and analysis as much as possible. The following pages

will hopefully provide an accurate and truthful survey of all major individuals,

artifacts, resources, citations, and milestones in the last one hundred years

of scholarship for ID.

Scope and Contents

The

main text of the present survey is primarily intended to be a basic field guide

for individuals and researchers without proprietary training in the fields

traditionally required for in-depth scholarship. The background broadly

explains the historical context of Sumer, Inanna, cuneiform, and the process of

artifact publication. The scholarship chronology covers the main contributions

by individuals and institutions for ID from 1889 to the present day. The future

of ID and conclusion speculate on interesting areas of future research. The

appendices provide what will hopefully be useful artifact, translation, and

publication information for the entire 412 lines of ID. The visualizations and

artifact catalog data tables in the appendices may be particularly useful to

seasoned researchers with formal training.

Background

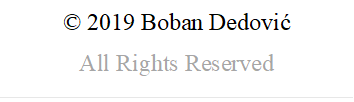

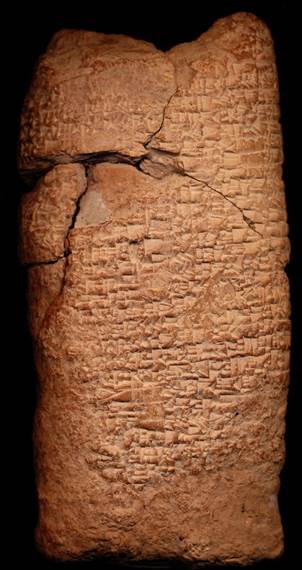

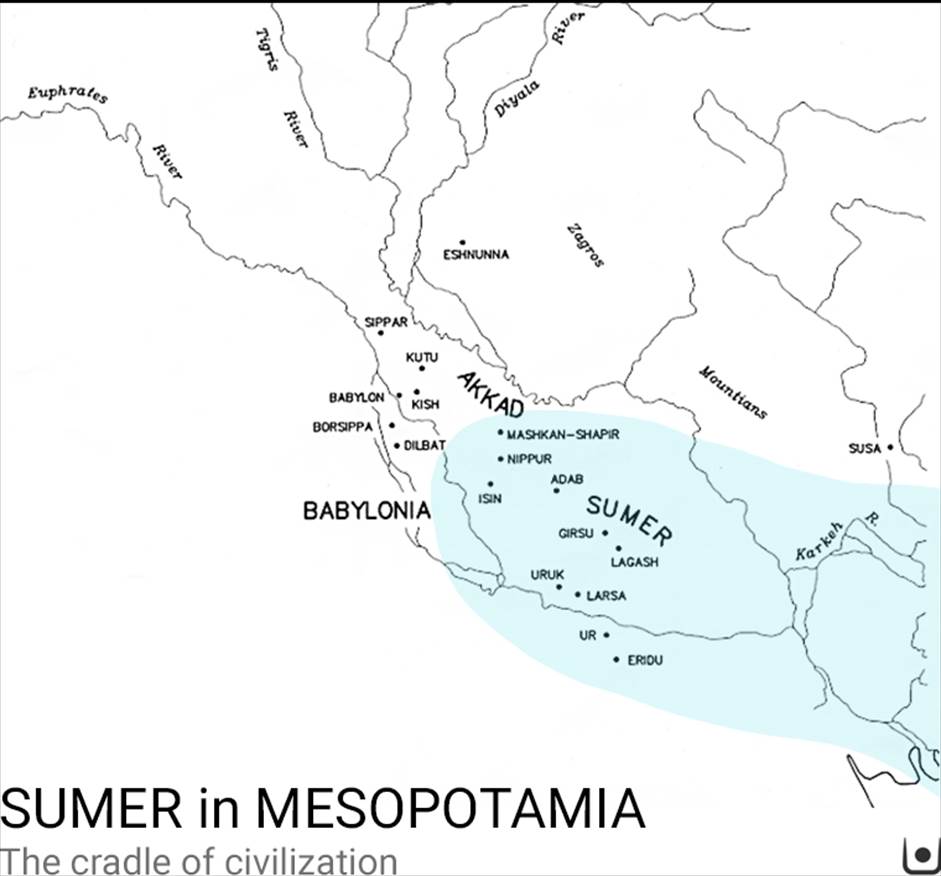

ID

represents an immensely important literary composition pertaining to a

significant deity in one of the world’s oldest civilizations—Sumer. Sumer was

an ancient civilization located in the southern region of modern-day Iraq,

situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The Zagros Mountains are located

to the north of the settlement area. This region is in the Middle East and

referred to as the fertile crescent, or Mesopotamia.[17]

Evidence suggests that long-term settlement and farming were practiced in

Mesopotamia by circa 4500 BCE.[18]

By ca. 1900 BCE, the Sumerian people were likely diffused into northern

Akkadian influence due to prolonged regional conflict.[19]

The time period from 4500 BCE to 1900 BCE is commonly known as the Chalcolithic

period, or Copper Age, and was followed by the Bronze Age. The duration of the

Sumerian empire has also been labeled as the Uruk period, and some notable city

settlements included Uruk, Ur, Eridu, Nippur, Lagash, and Kish.[20]

Figure 1.1.

SUMER in MESOPOTAMIA. Digital Illustration by OMNIKA

Foundation. “Inanna’s Descent Myth & Summary,”

OMNIKA: Digital Library of Mythology (OMNIKA Foundation), May 3, 2019,

https://omnika.conscious.ai/myths/inanna-descent.

Finally, it is worth noting that the name Mesopotamia originates from the Greek

word Μεσοποταμία, which

means “land between rivers.” It was in this region that civilization as we know

it came to be—likely as a consequent of the world’s first cities.

Inanna

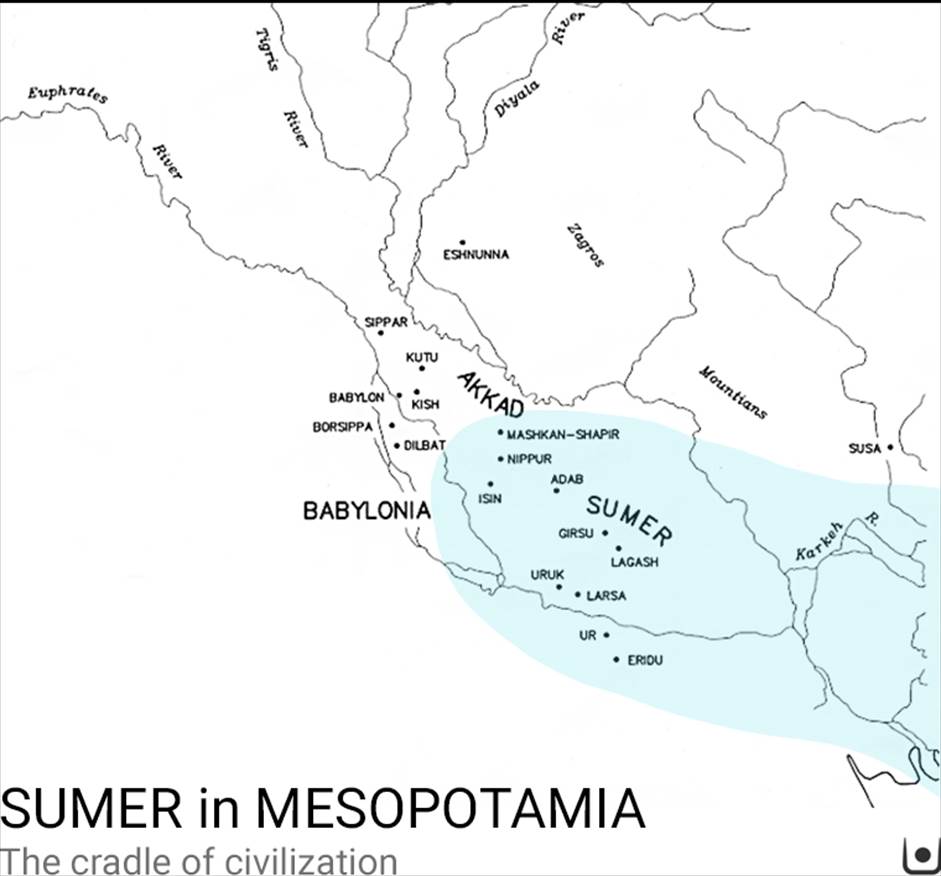

Inanna

had a special place in Sumerian history and was perhaps considered the most

beloved deity of her time.[21]

Cities such as ancient Nippur and Ur all had temples erected and dedicated to

Inanna, along with artwork in the forms of vases, masks, and cylinder seals.[22]

Figure 1.2.

Cylinder seal VA 243. Museum artifact

published by Anton Moortgat, “West Asian Cylinder Seals,” Vorderasiatische

Rollsiegel (1940): 101. [The figure to the far left may depict Inanna]

While scholars do not always agree with one another when it comes to

identifying deities, certain symbolic indicators do give helpful clues. For

example, Inanna was often associated with the symbol of an eight-pointed star.

The ambiguity of precise symbolic identification must be stressed because both

Sumerian and Akkadian cultures featured Inanna prominently.

Like the seal, the

Mask of Warka, pictured below, featuring the Lady of Uruk,

may be Inanna.

Figure 1.3. Mask

of Warka (3200–3000 BCE). Alabaster carving of the Lady of Uruk.

Photograph by Osama S. M. Amin, uploaded May 10, 2019. Wikimedia Commons

(Baghdad: National Museum of Iraq). [Pictured on title page]

The Mask of

Warka is an alabaster carving that seemingly features a female head with

thin lips, broad and connected eyebrows, a chipped nose, as well as a pair of

fierce, wide eyes. Even if it was not carved after Inanna’s likeness, it is

still regal and divine in both posture and tone.

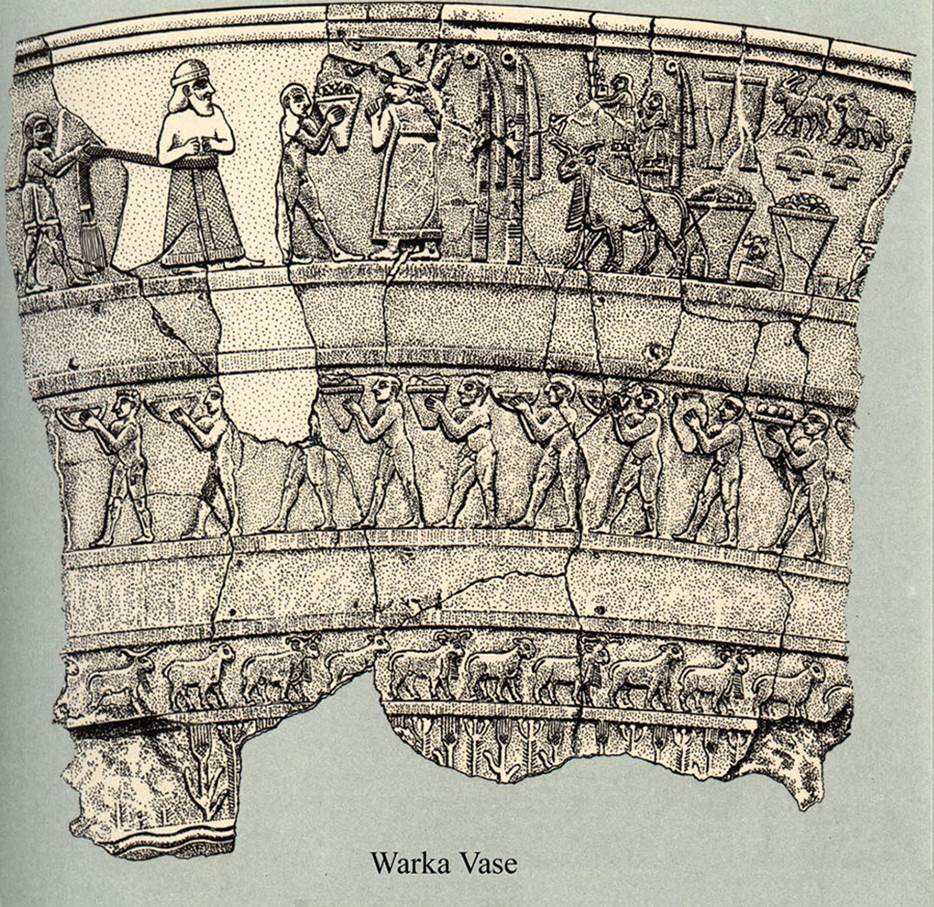

Figure 1.4.

Warka Vase. Lost Treasures from Iraq, Iraq Museum

Database, last modified April 14, 2008,

http://oi-archive.uchicago.edu/OI/IRAQ/dbfiles/objects/14.htm.

Another related artifact at the Iraq Museum is the Warka Vase. The vase

seems to picture lines of naked men giving offerings to what appears to be

Inanna (in the middle at the top). The double staffs at her side have been

cited as indicators of this deity.

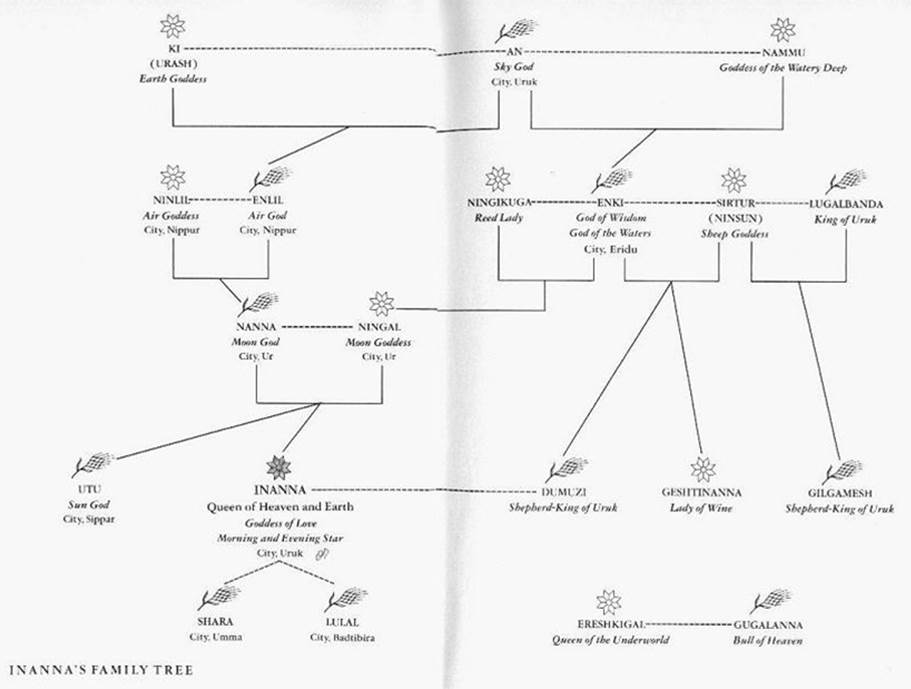

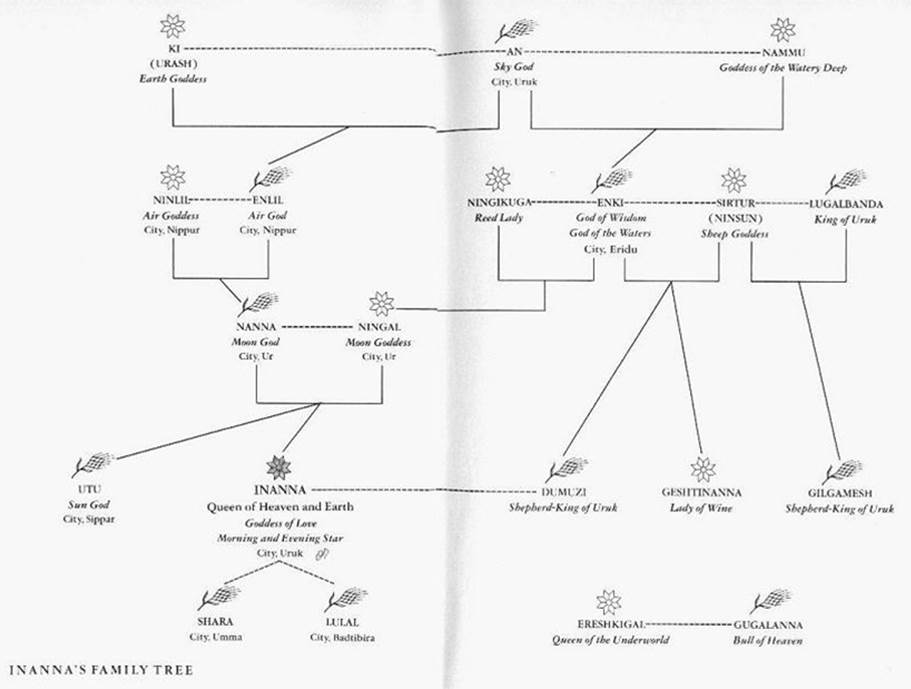

Scholars

have attempted to decipher Inanna’s family tree with respect to other Sumerian

deities without consistent agreement. Samuel N. Kramer depicted Inanna as the

Queen of Heaven and Earth, birthed by the moon god Nanna and moon goddess

Ningal, and laterally related to the sky god An and water goddess Nammu.

Figure 1.5. Inanna’s

Family Tree. Artwork

by Elizabeth Williams-Forte. Samuel N. Kramer and Diane Wolkstein, Inanna:

Queen of Heaven: Hymns from Sumer (New York: Harper & Row, 1983): x-xi.

As shown in

Kramer’s 1983 publication, the family tree is both extended and symbolically

represented by animals, cities, and celestial bodies. The exact nature of these

relationships differs by the time period, composite myth, parent culture, and

scholar doing the interpretation.

Cuneiform

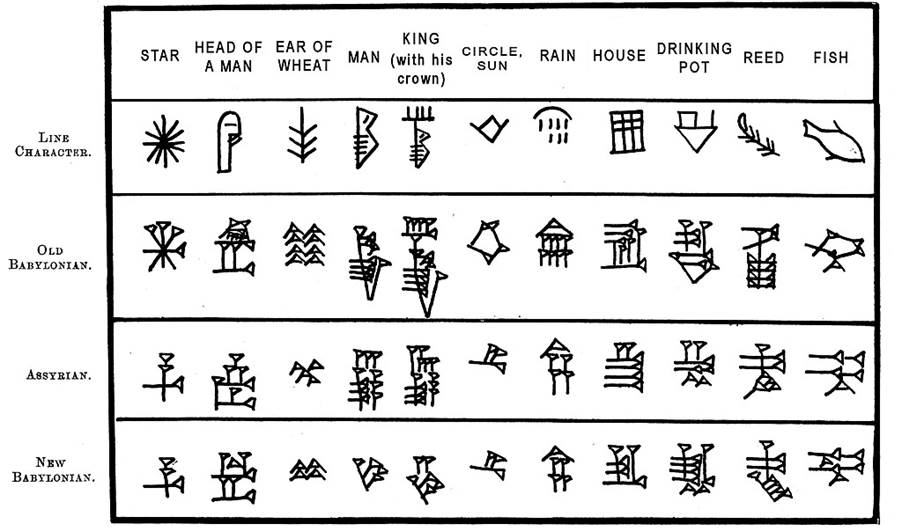

Whatever

the exact fourth-millennium origin date of cuneiform was, scholars recognize

that ancient Sumer was one of the earliest civilizations on our planet with a

surviving writing system. The Sumerian language may be considered a linguistic

isolate—that is, there is no known parent language from which it is derived.[26]

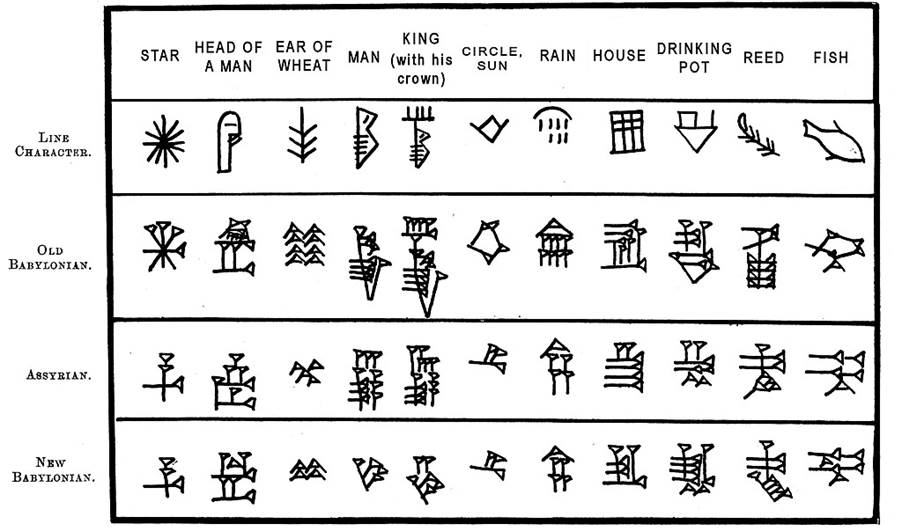

Cuneiform, literally meaning wedge-shaped, is a form of writing traditionally

inscribed on soft clay tablets with a reed stylus.[27]

The little wedge-shaped marks represent symbols and can be combined into

coherent sentences read from left to right. Unlike wood or papyrus that can

deteriorate, once the clay tablet cools off, the inscription can last for

thousands of years. It is widely believed that cuneiform came from more

primitive pictures representing symbols, which were then turned sideways and

simplified to basic lines.

Figure 1.6. Table

illustrating the simplification of cuneiform signs. Illustration

by Ernest A. Budge and Sir Leonard W. King, A

Guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian Antiquities (London: British Museum

Trustees, 1922), 22.

A

few minor but important details about cuneiform and language are worth

mentioning. First, cuneiform is a form of script, not a language. It is more

appropriately labeled as an alphabet. Second, it is important to distinguish

between Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, and other related languages. While these

civilizations were in close physical and cultural proximity (overlapping and

diffusing eventually) to one another, the languages were not one and the

same.[28]

Third, writing systems, alphabets, and display forms are also different from

language, grammar, and usage. While the Akkadian language may have used the

cuneiform script, its language was different from Sumerian.[29]

Finally, while cuneiform script usage may date back to as early as 9,000 BCE,

most artifacts before the fourth-millennium BCE represent systems of accounting

or record keeping.[30]

Almost 95 percent of all Sumerian cuneiform artifacts fall into this former

category, and all known literary works like ID are likely less than six

thousand years old.[31]

While much more can be said about the differences between script, language, and

the cultures of the ancient Near East, existing scholarship has covered these

topics extensively.

Clay to Composition

The

publication of a coherent and readable English translation like the ETCSL

version is not a linear path with a small number of scholars doing the work

start-to-finish. Institutions like museums, universities, and governments must

secure funding from their stakeholders for archaeological expeditions into geographical

areas of interest. Except for tasteless exceptions like war and plunder, these

institutions must acquire permits and negotiate arrangements with local

governments (and sometimes local peoples) to secure permission for digging in

the ground. Having met these requirements, institutions then send their able

and qualified associates into the field to coordinate the work of

archaeology. Discovered artifacts may be documented at that time, or they may

be boxed and shipped to the institution that secured ownership rights during

prior negotiations.

Once

relocated, the long process of restoring and publishing artifact findings takes

place. Restoration is oftentimes required because the artifacts may be

fragmented, weathered, or otherwise destroyed. Cataloging usually takes place

in some form or another, hence why we will read artifact names like CBS 9800

and YBC 4621. The cataloging systems differ by institution and will likely have

little to no association with the contents of the artifact.

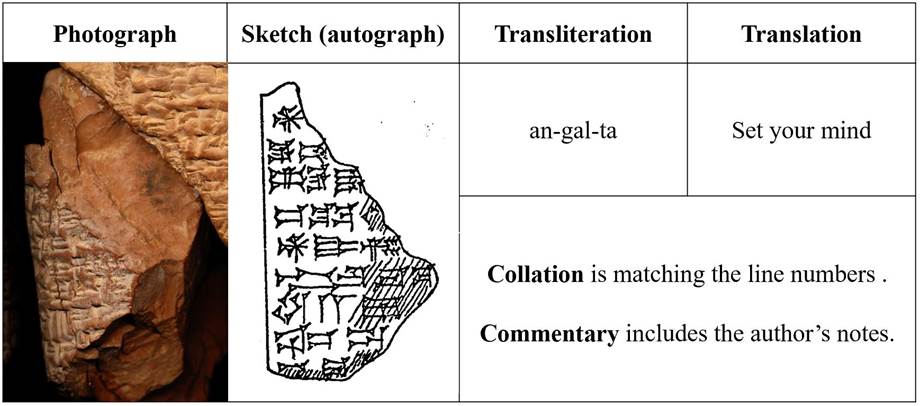

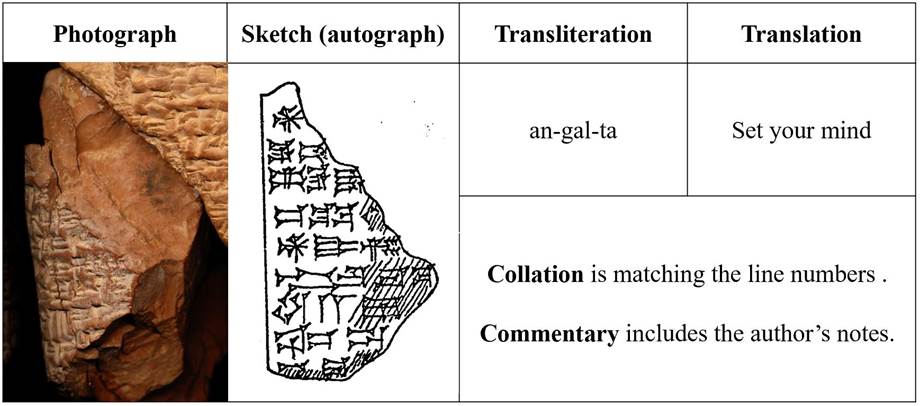

Initial publication may take place whereby photos or sketches of the symbols

are made available to other scholars or the general public. As is common with

cuneiform script-based languages like Sumerian, the symbols need to be

transliterated before they can be translated. Transliteration is “the method of

mapping from one system of writing to another based on phonetic [pronunciation]

similarity.”[33]

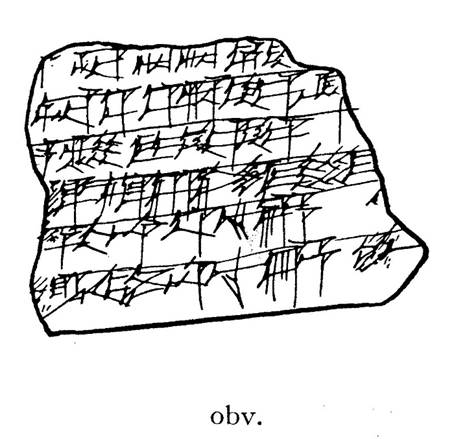

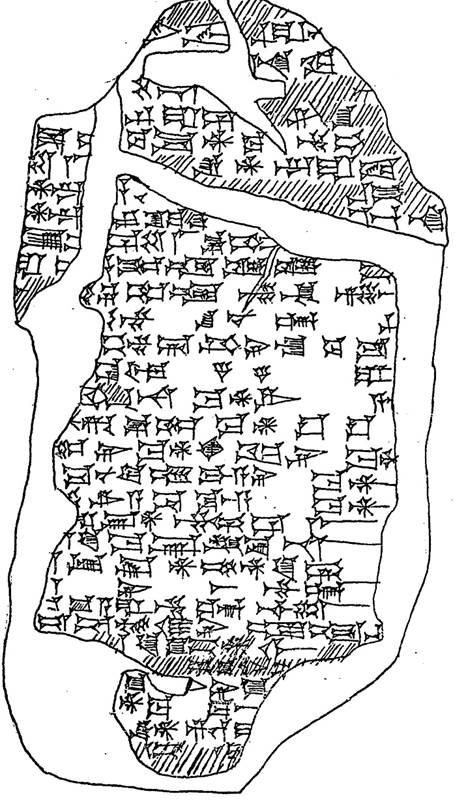

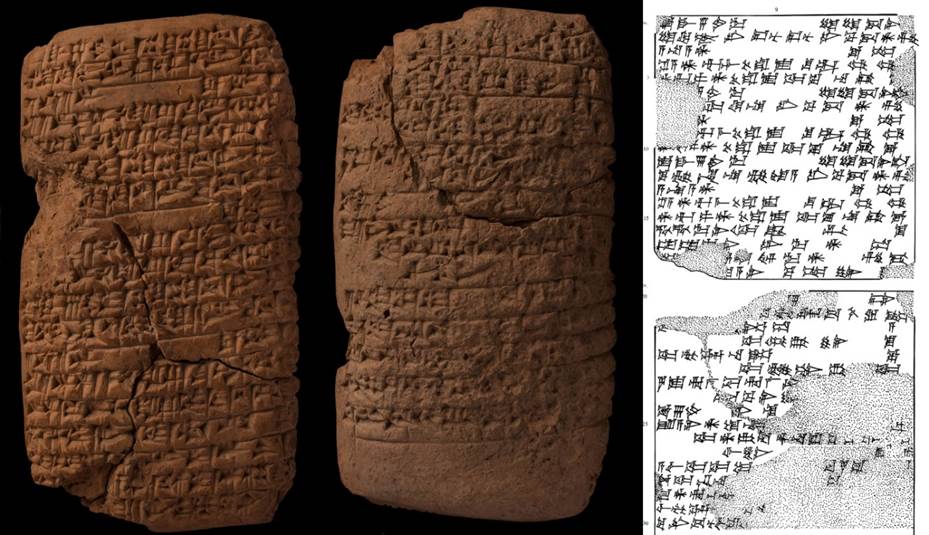

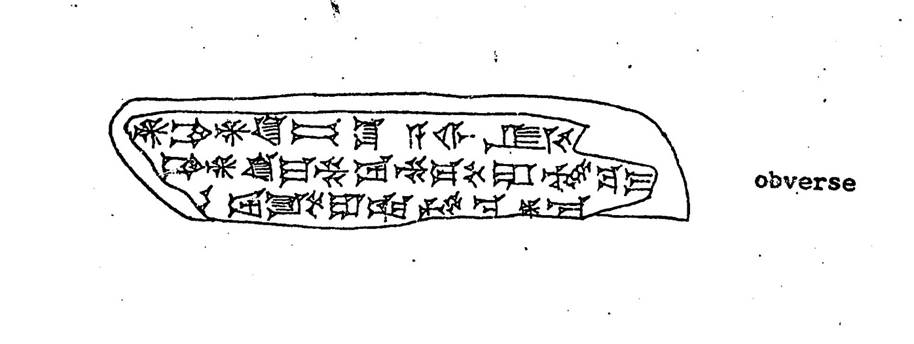

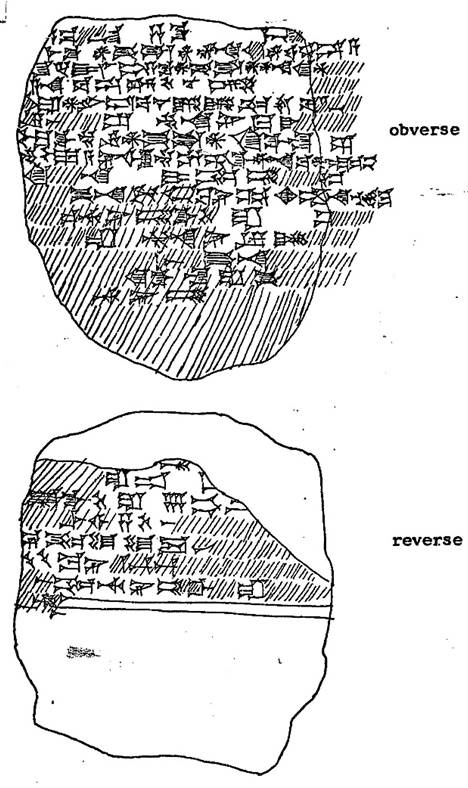

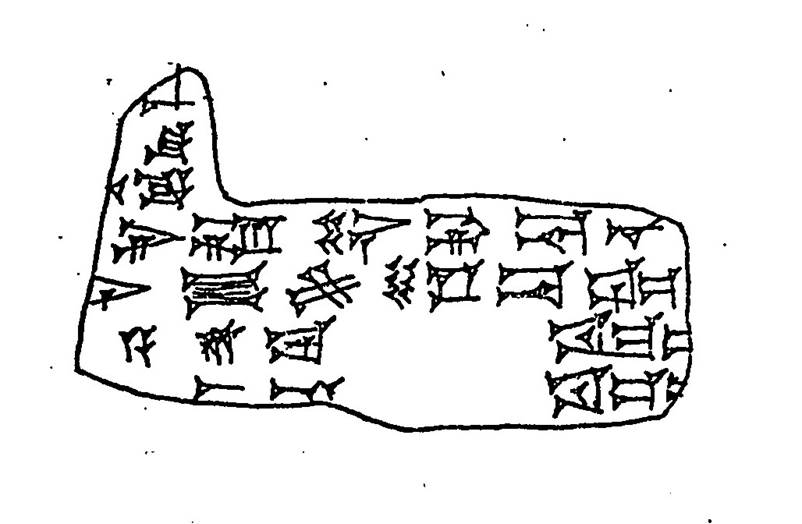

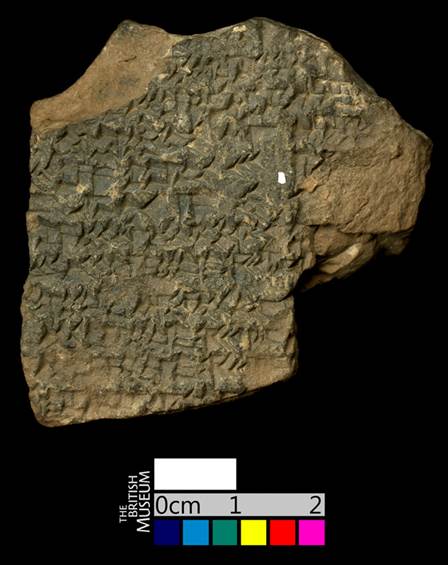

Figure 1.7. Artifact terminology table.

Illustration composite by Boban Dedović; Artifact photo by CDLI (see

artifact N 953); Artifact sketch by William R. Sladek, “Inanna’s Descent,” 288,

Figure VIII. [The translation depicted is only for illustration purposes]

Translation is

mapping the meaning of text in one language into another with as much accuracy

as possible. An artifact or source related to a specific composition may also

be called a witness. Collation means mapping the transliteration lines

to a corresponding line in the translation. It must be mentioned that there are

many other complexities and challenges associated with the process and

limitations of collating translations. When we read that a scholar published

artifact findings, we must, therefore, understand that this may mean

photographs, sketches (also known as autographs and sometimes published

as plates), transliterations, translations, or a combination of several

types.

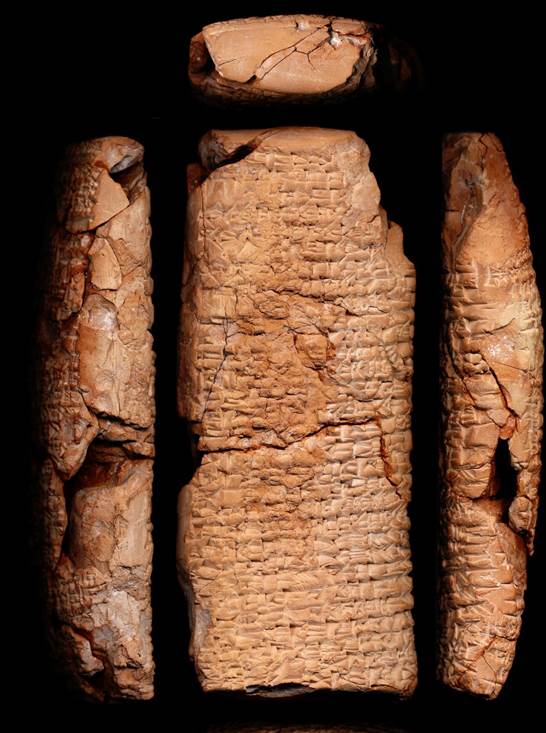

Because

of the fragmented nature of artifacts and partial publications, it may take

several scholars many years before a complete rendering of a story or myth is

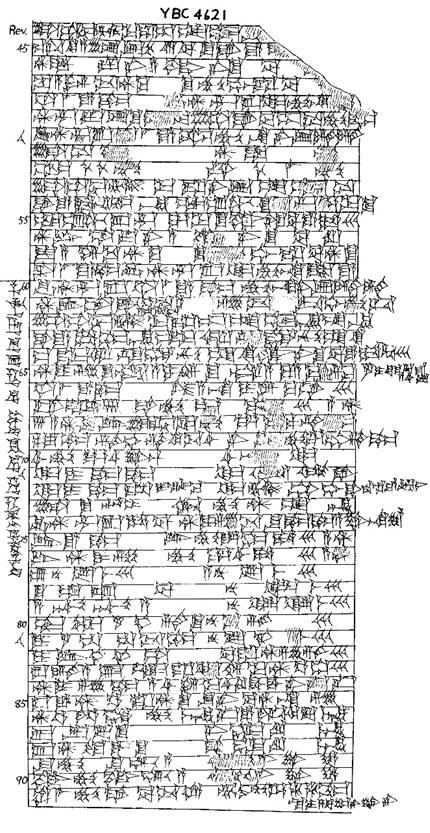

possible. Some artifacts, like YBC 4621, provide some ninety lines of text for

ID while others merely provide insight into how many lines long a missing gap

is.[34]

In the case of ID, almost fifty years passed between the initial discovery of

five artifacts to the publication of over half of the full translation (250

lines). Some scholars conducted the archeology, others published photographs

and sketches, while others did restoration work to enable translators. Once

enough artifacts are associated with a given contextual theme, they may be

organized into a composition. A composition is another name for a coherent

translation of a story that seems to be fit for standing alone. Any critical

mistake or oversight during a single step of this laborious process may set

back the accuracy of a composition for decades. Consequently, the speculative

and difficult nature of the publication process must be highlighted so that we

can see a complete translation of ID with the appreciation it deserves. As

uninformed readers, we cannot easily appreciate the years scholars spent getting

their hands dirty with digging, cleaning, and restoring clay objects so

that other scholars half a world away could attempt to decipher what they mean.

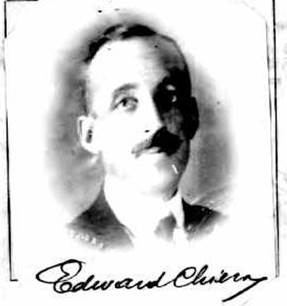

Scholarship Chronology

The

chronology of scholarship for ID is most easily understood as a timeline from

1889 until the present day. During this period, five scholars and five major

institutions primarily contributed their efforts toward publishing findings on

some fifty artifacts and 412 lines of translated text. While many

scholars contributed to the decipherment of ID, Edward Chiera, Samuel Noah

Kramer, Cyril John Gadd, Bendt Alster, and William R. Sladek may be candidates

for what we can call the big five.[35]

|

Edward

Chiera

|

Samuel

N. Kramer

|

Cyril J.

Gadd

|

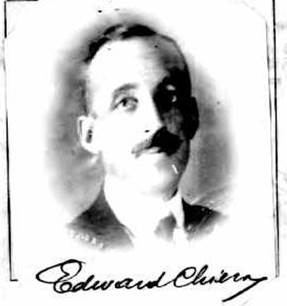

Figure 1.8. Three of the ‘big

five’ of ID. Illustration composite by Boban Dedović; Photograph of

Edward Chiera’s 1924 passport application by unknown author, uploaded May 31,

2011, accessed May 1, 2019, Wikimedia Commons,

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Edwardchiera1924.jpg; Photograph of

Samuel N. Kramer. Thorkild Jacobsen, “Samuel Noah Kramer (1897-1990),” Archiv

für Orientforschung 36./37, no. Bd (1989/1990): 198. Photograph of Cyril J.

Gadd by unknown author. D. J. Wiseman, “Obituary: Cyril John Gadd,” Bulletin

of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 33, no.

3 (1970): 595. [Photographs of Sladek and Alster could not be located]

The five major

institutions that secured funding and sponsored coordination for such efforts

related to ID include the University of Pennsylvania, the University of

Chicago, the British Museum, Oxford University, and the University of

California at Los Angeles.[36]

Together, these individuals and institutions were involved with the discovery,

publication, and decipherment of most of the artifacts and roughly 370 lines of

ID.

Discovery

and Initial Publication (1889-1919)

The

first known artifacts containing ID were discovered in Nippur, modern-day

central Iraq, between 1889 and 1900. The University of Pennsylvania (hereafter

Penn or Penn Museum) and the Istanbul Museum of the Ancient Orient[37]

(hereafter Ottoman Museum) jointly conducted four archaeological expeditions in

what was then part of the receding Turkish empire.[38]

The two parties agreed that Penn would fund the expedition in exchange for

ownership of half of the recovered artifacts.[39]

This arrangement resulted in thousands of artifacts being boxed and transported

a world apart—effectively separating the scholarship efforts between

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Istanbul, Turkey.[40]

The artifacts were not cleaned, restored, documented, compiled, translated, and

published at the time of discovery; instead, many scholars spent the next fifty

years collaborating and independently publishing their findings.

In

1914, Stephen Herbert Langdon (1876-1937),[41]

an American born British Assyriologist, published the first two fragments

containing snippets of the myth.[42]

In the same year, Arno Poebel published three other fragments from Penn’s

museum.[43]

With the initial five pieces published, in 1916, Langdon published the first

translation of ID and named it the “Sumerian original of the Descent of

Ishtar.”[44]

Up until 1916, many scholars were familiar with the Assyrian myth known as “The

Descent of Ishtar.” This version was shorter, and in many contextual ways, very

different from ID.[45]

With the first publication of ID, scholars recognized that Inanna was a

Sumerian deity, and the Assyrian version was adapted from the former. At this

point, ID was comprised of less than thirty lines of text, and its meaning was

obscure.

More Artifacts and Assignments (1920-1934)

Major

breakthroughs in artifact publication and composition assignment came when

Edward Chiera (1885-1933)[46]

emerged into the fold. Throughout his career, Chiera was an incredibly

important figure in the history of ID. Mainly, he was involved with almost

every major museum and academic institution that owned tablets containing ID:

Penn, Chicago, and the Ottoman Museum. Chiera was also known for creating

extremely detailed and precise sketches of the artifacts he came into contact

with. In 1923, Chiera spent a year in Istanbul sketching various tablets from

the Nippur excavations and published his findings in 1924.[47]

After his return to Penn in the same year, he spent several years restoring and

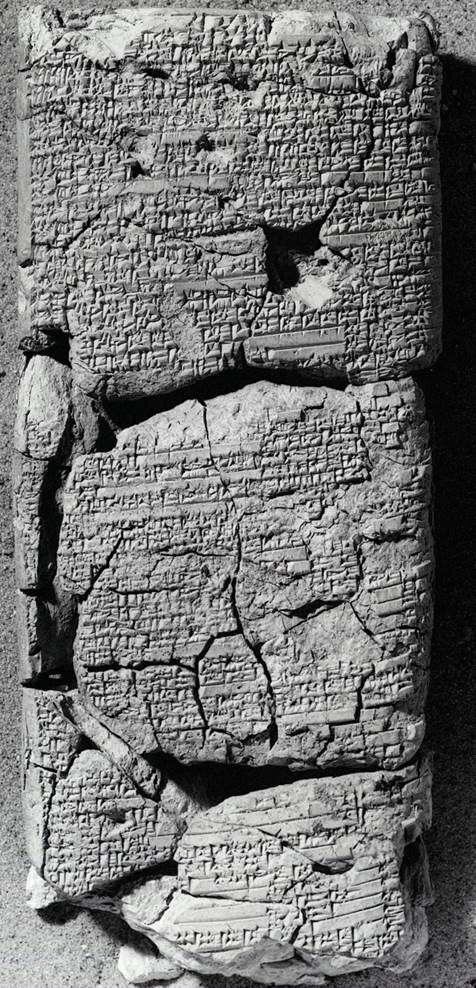

documenting some three hundred artifacts. Most critically, he discovered that

the previously unpublished Penn tablet, named CBS 9800, was joined with (part

of another fragment) the Ottoman Museum’s Ni 368 tablet.

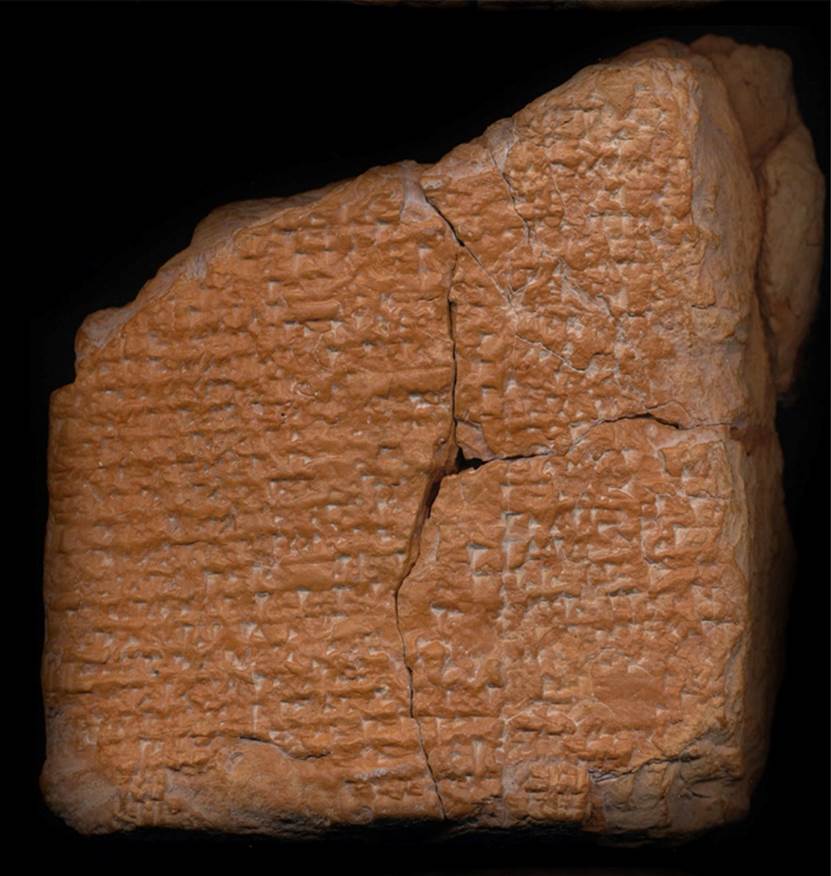

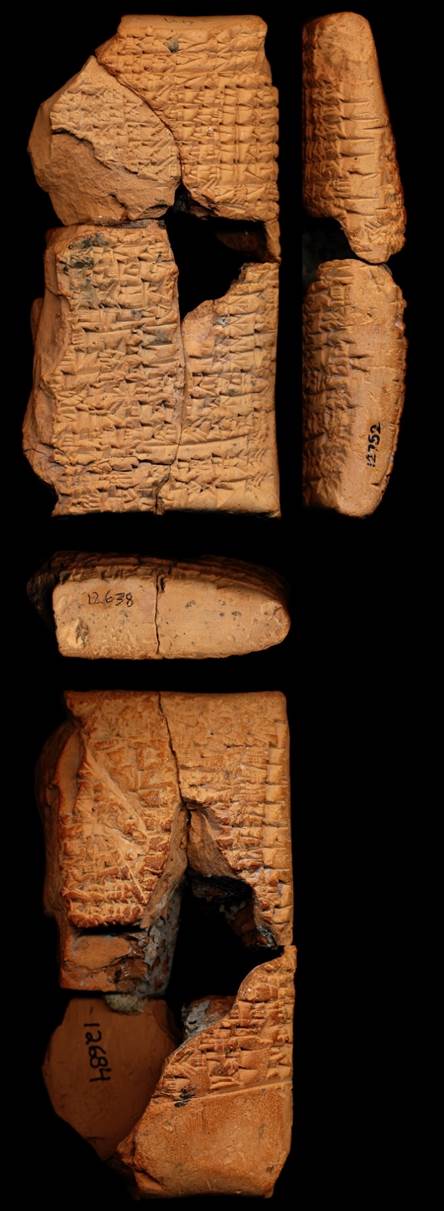

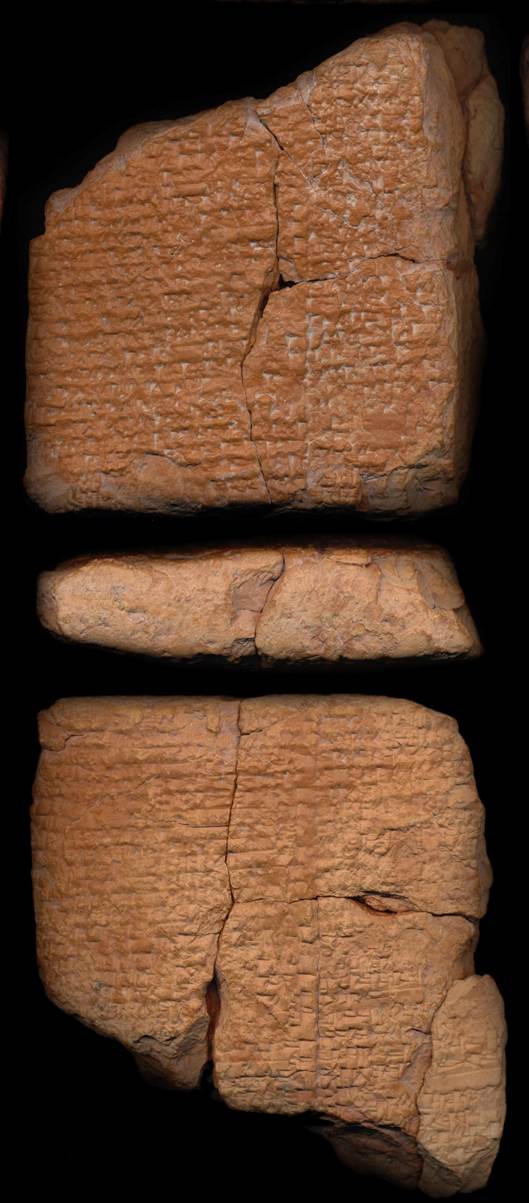

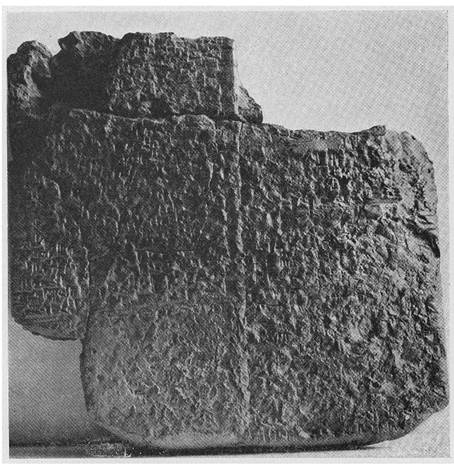

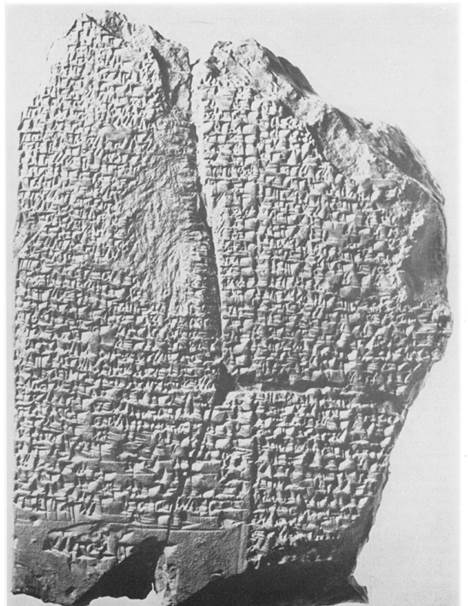

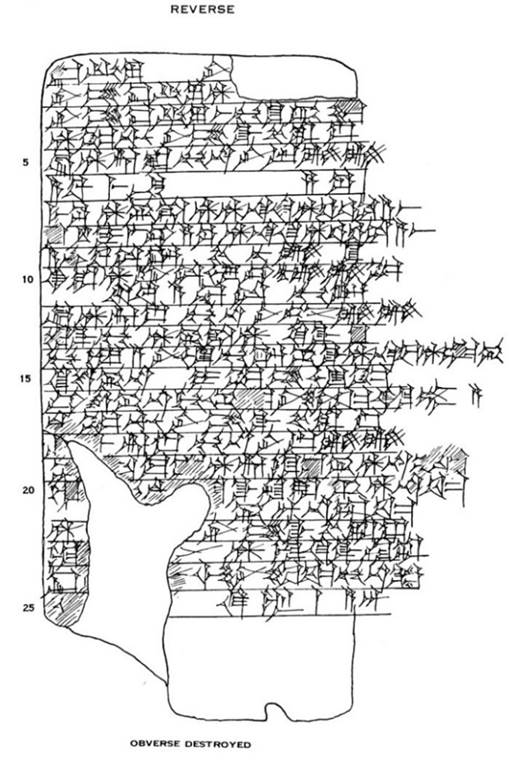

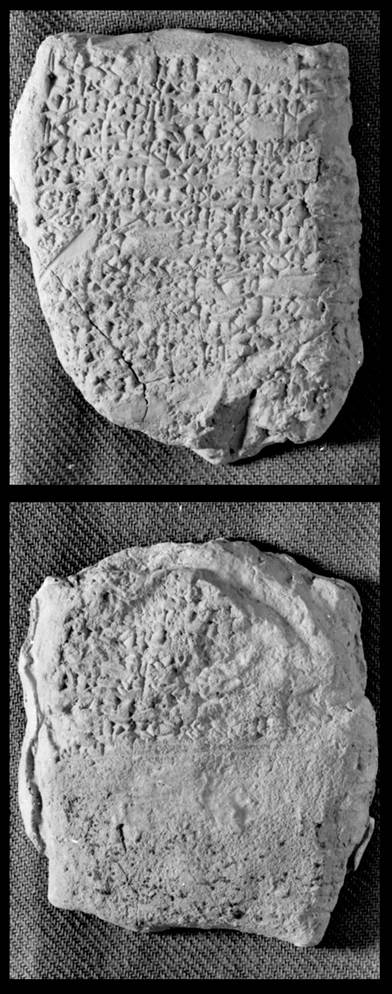

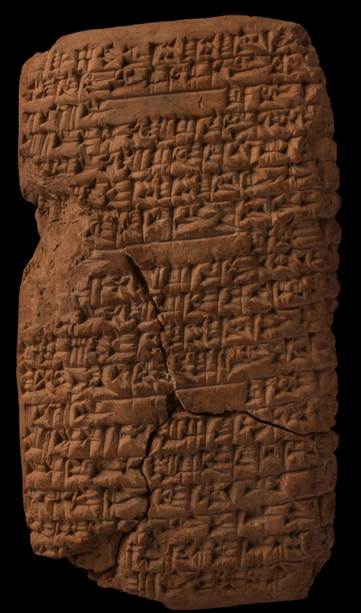

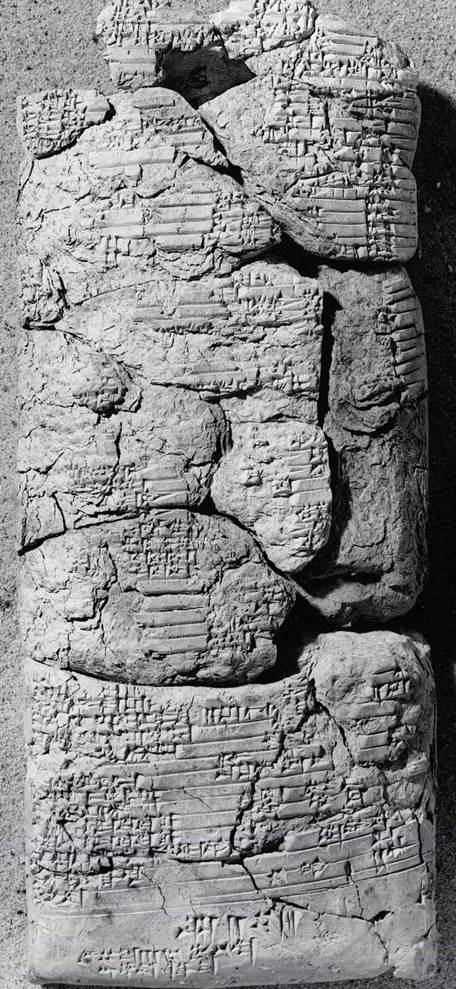

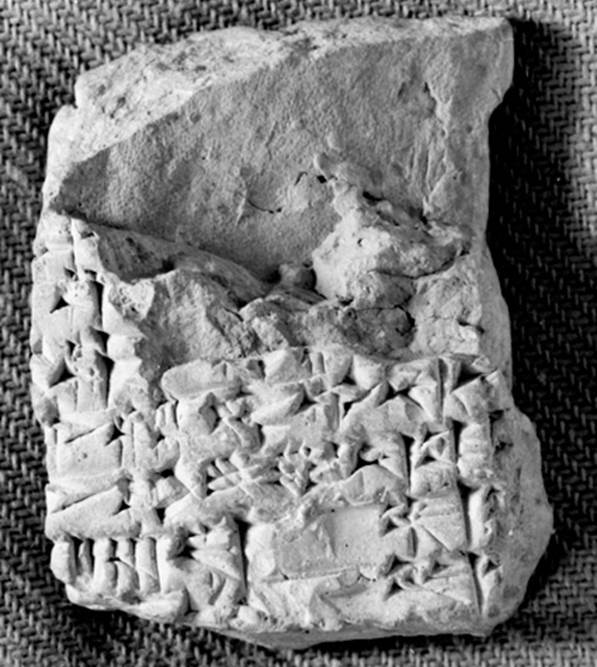

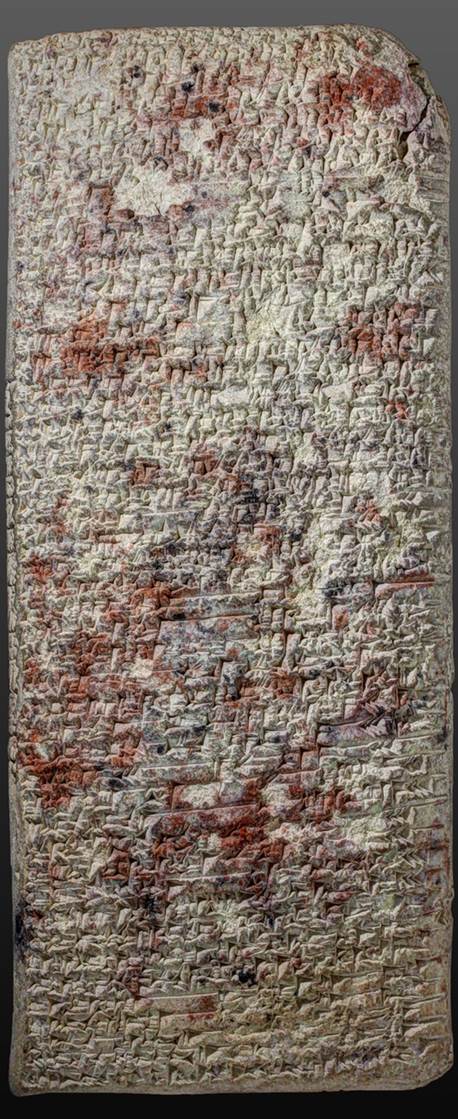

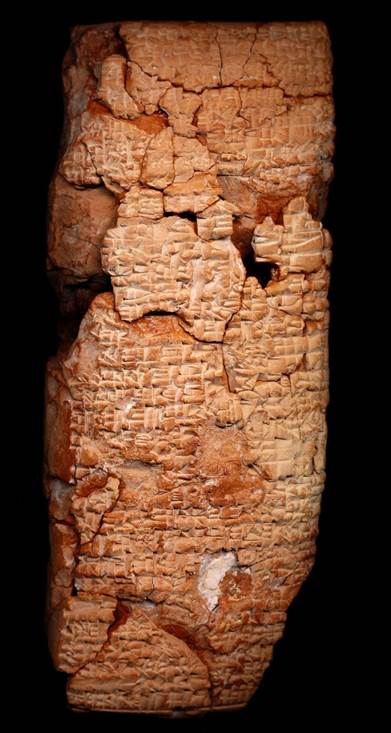

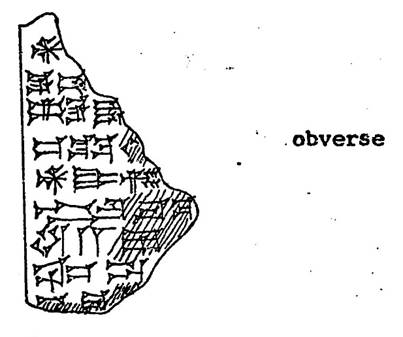

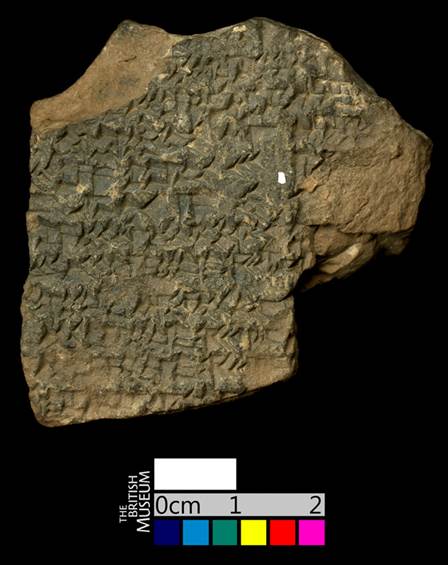

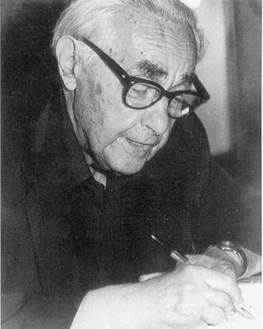

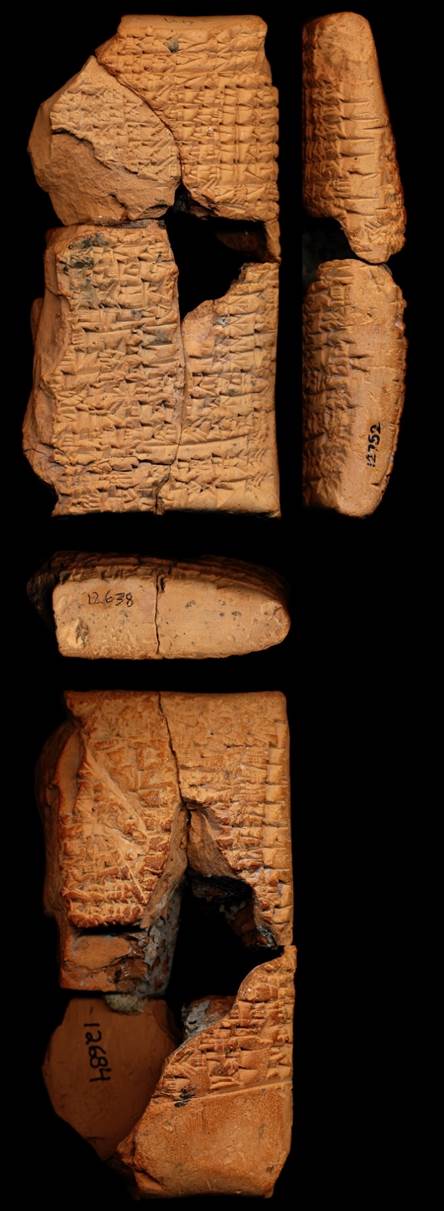

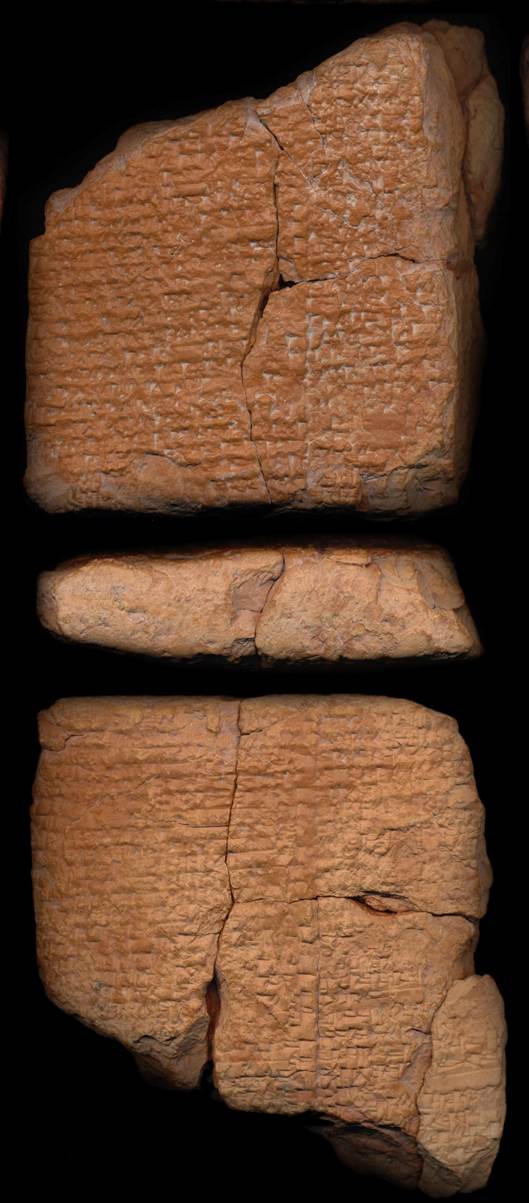

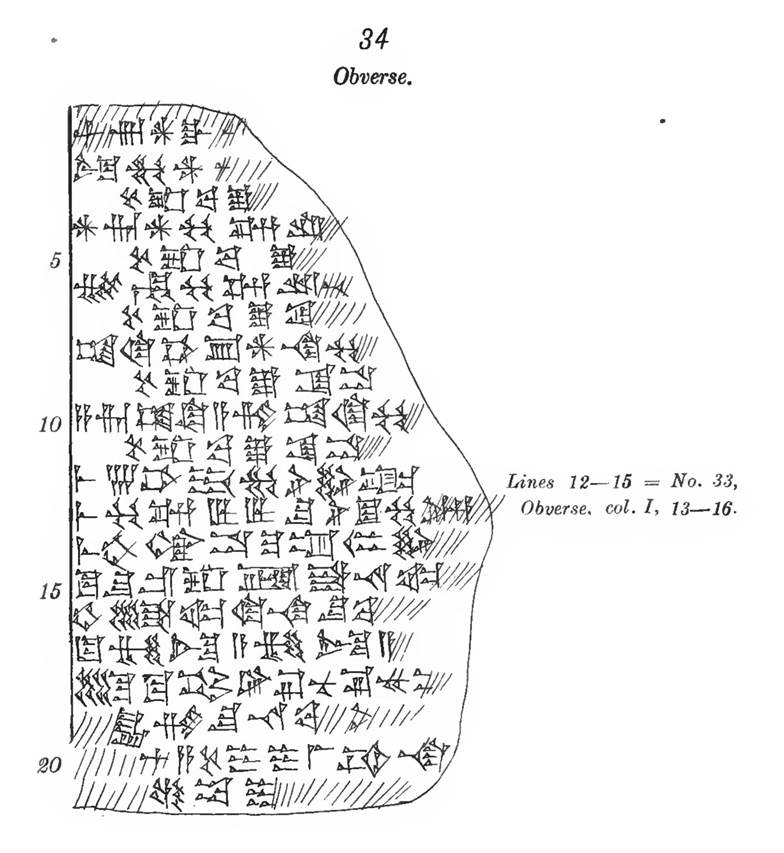

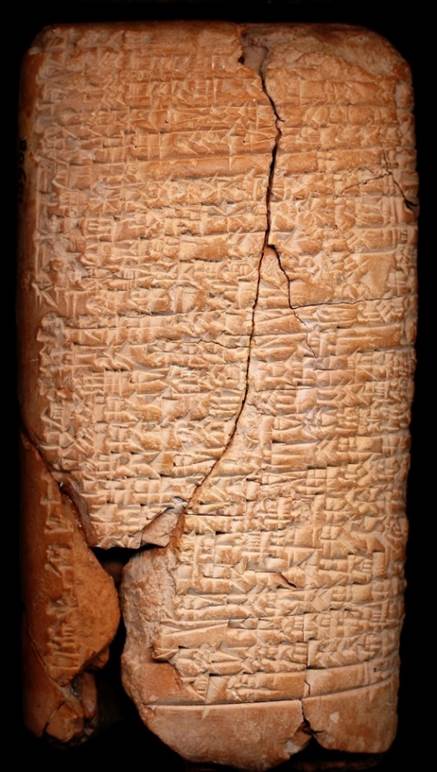

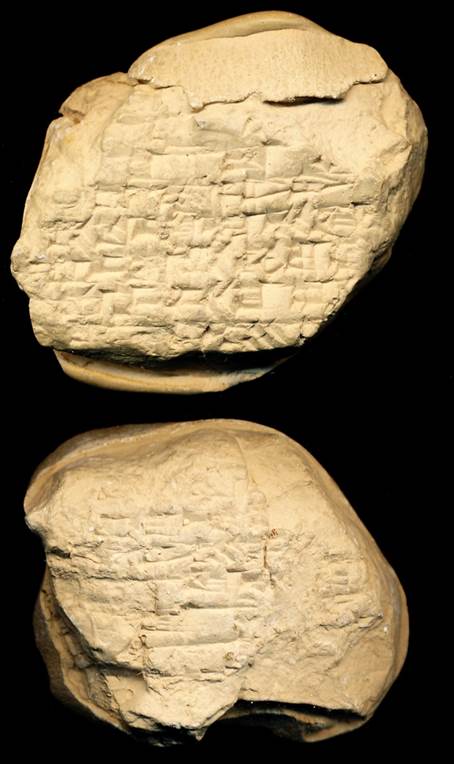

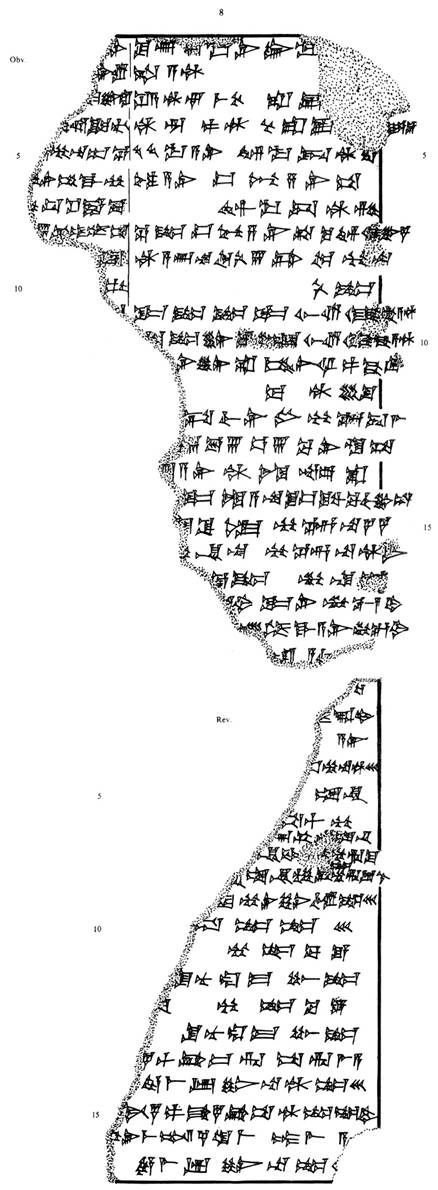

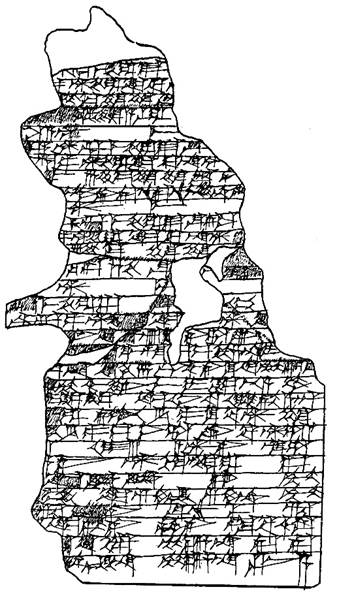

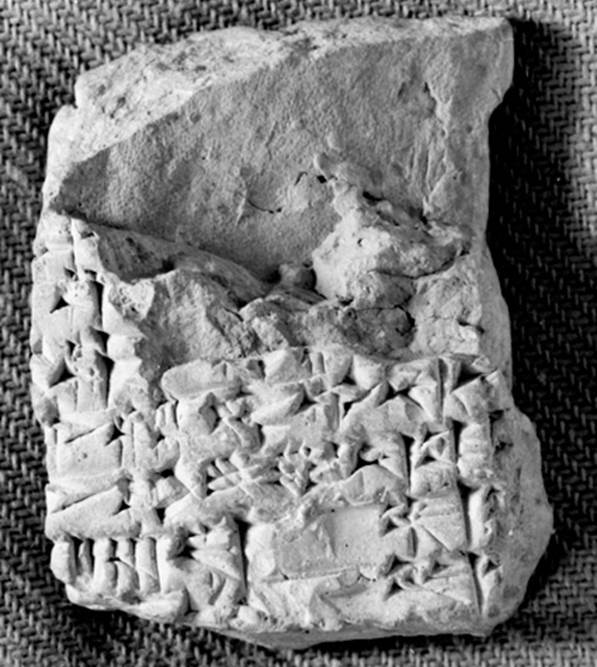

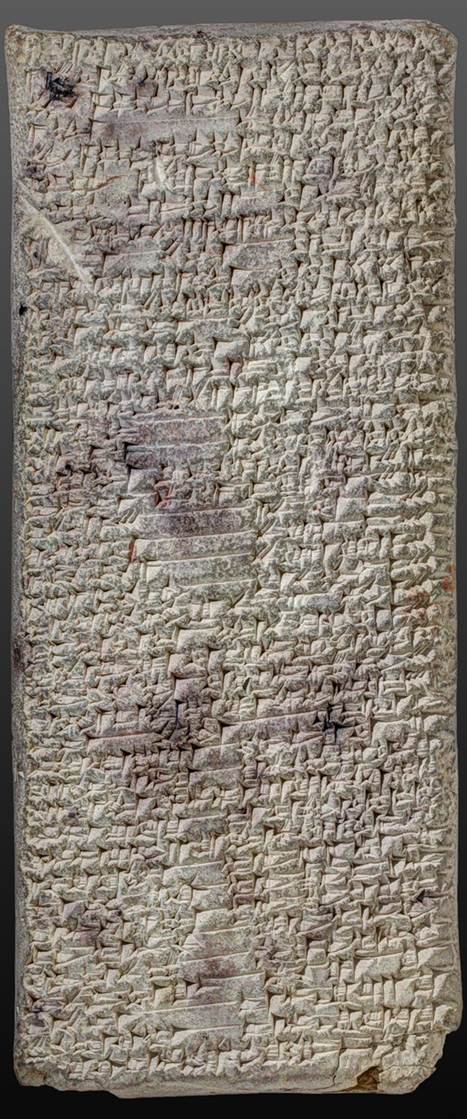

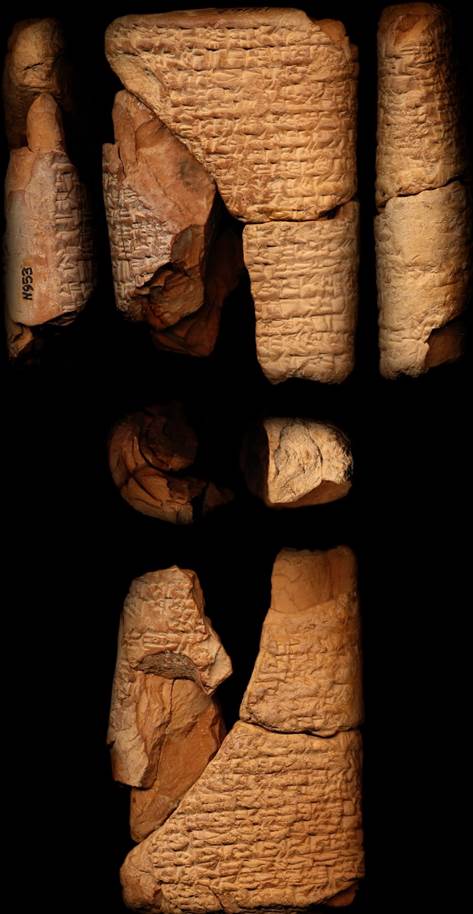

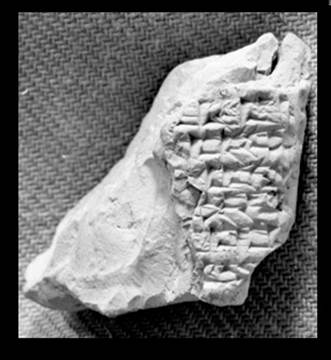

Figure 2.1. Artifact

CBS 9800. Photograph, "Archival view of

P345344." Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI), University of

California at Los Angeles (UCLA), accessed May 1, 2019,

https://cdli.ucla.edu/search/archival_view.php?ObjectID=P345344. [Obverse

side]

Together, these

two tablets produced almost 250 out of the 412 lines of text we have today.

Chiera continued contributing toward locating various fragments and was

preparing to publish his findings until his untimely death in 1927.[48]

His findings were posthumously published in 1934 by Samuel N. Kramer,[49]

a prominent Sumerian scholar we will cover extensively in this survey.

Before

proceeding, it is important for the reader to understand basic terminology related

to cuneiform tablet artifacts. When obverse and reverse are mentioned, this

refers to the front and the back. A side may occasionally have content on it,

but this is rare among artifacts related to ID. Consequently, a single tablet

may have upwards of four photographs of it. A plus sign “+” or the word join

notates that the tablets are fragments that were originally one piece. In the

case of CBS 9800 and Ni 368, we may see them notated as “CBS 9800 + Ni 368.” “1

Ni 0368” or “1st Ni 0368” means that it is the first edition (copy)

of that fragment and subsequent copies were baked to replicate its contents.

Finally, the word column (abbreviated as Col. I for example) means an intended

physical separation of line blocks. Scholars vary in their practices of

documenting line numbers, columns, and other markers, but it is unlikely to see

a composition name listed (e.g., you likely will not see “Inanna’s Descent”

listed on the artifact photographs or sketches).

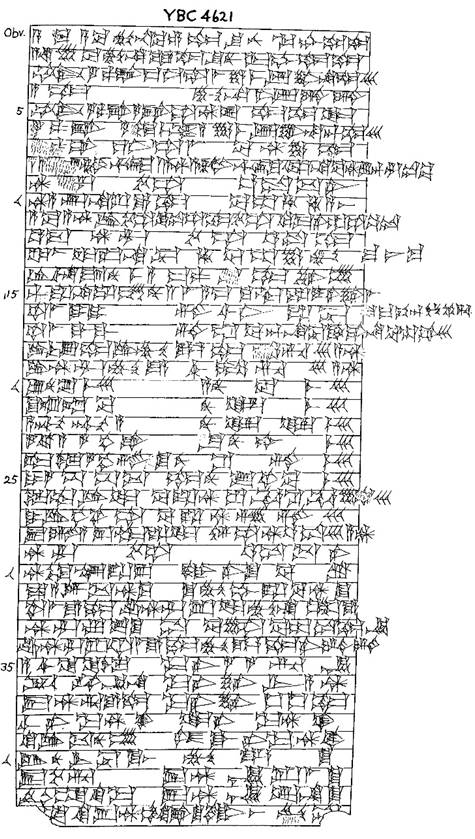

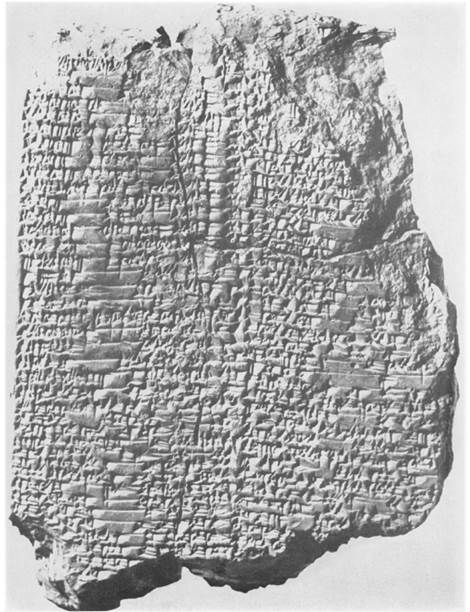

Before

Chiera passed away, he provided one more instrumental contribution to the

myth’s composition: the association with an unpublished tablet named YBC 4621

(now YPM BC 018686)[50]

from Yale’s Peabody Museum.[51]

This tablet provided ninety-one lines of text and was preserved in excellent

condition. The picture below shows how both complete and stunning this

unusually well-preserved artifact is.

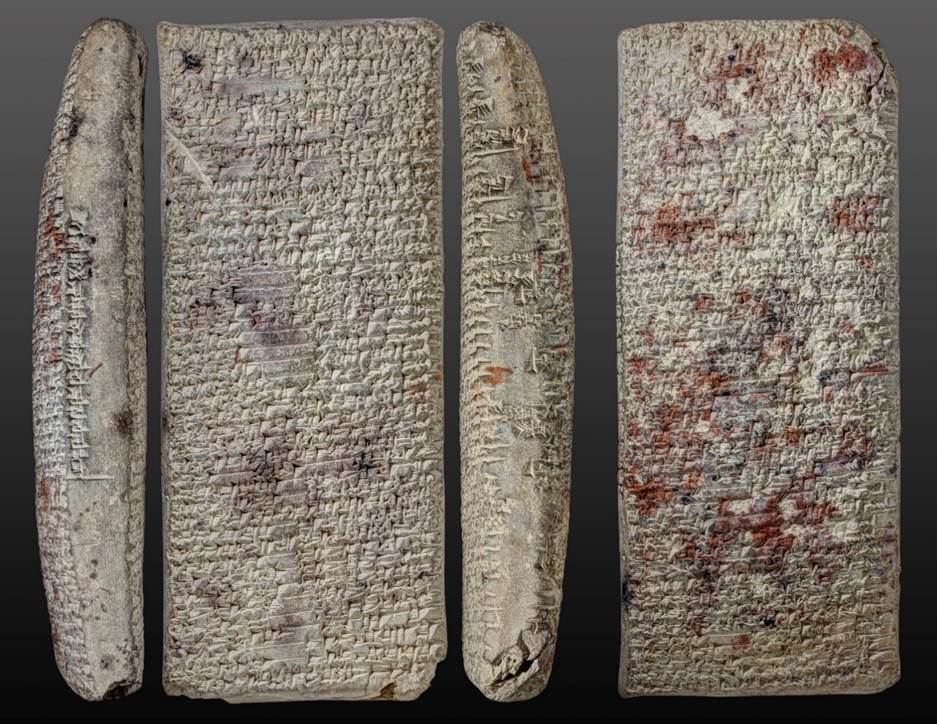

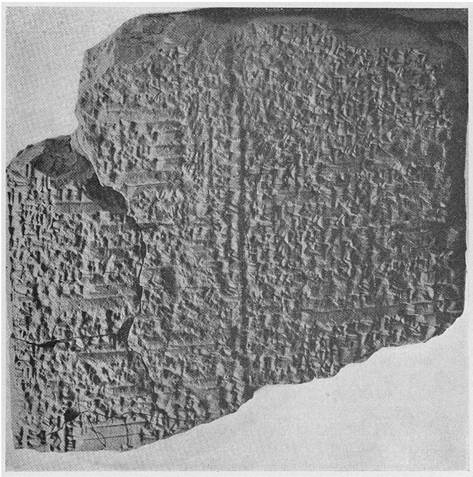

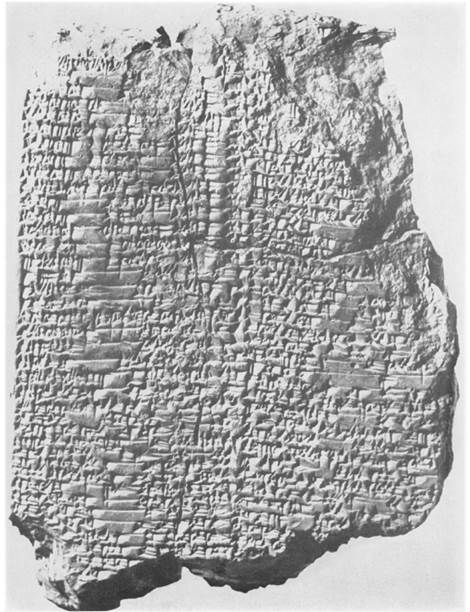

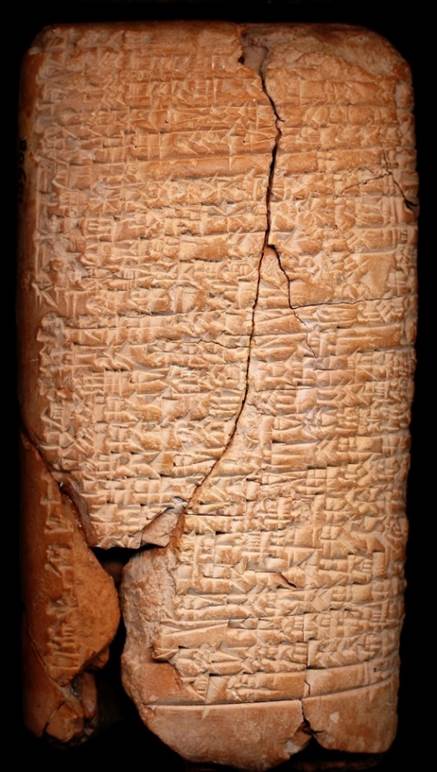

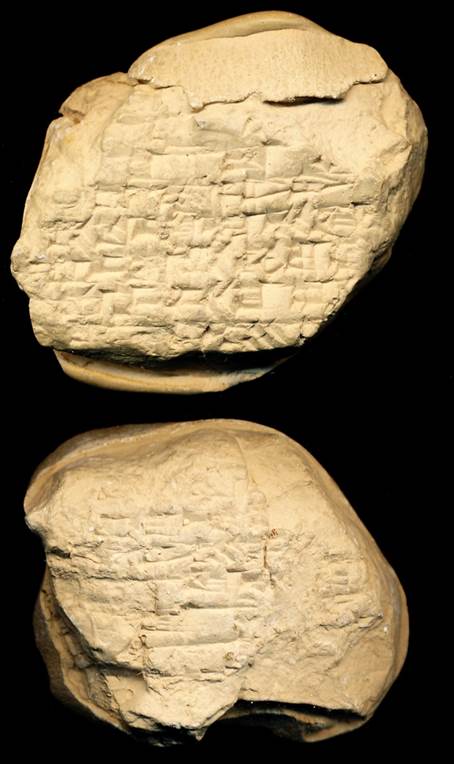

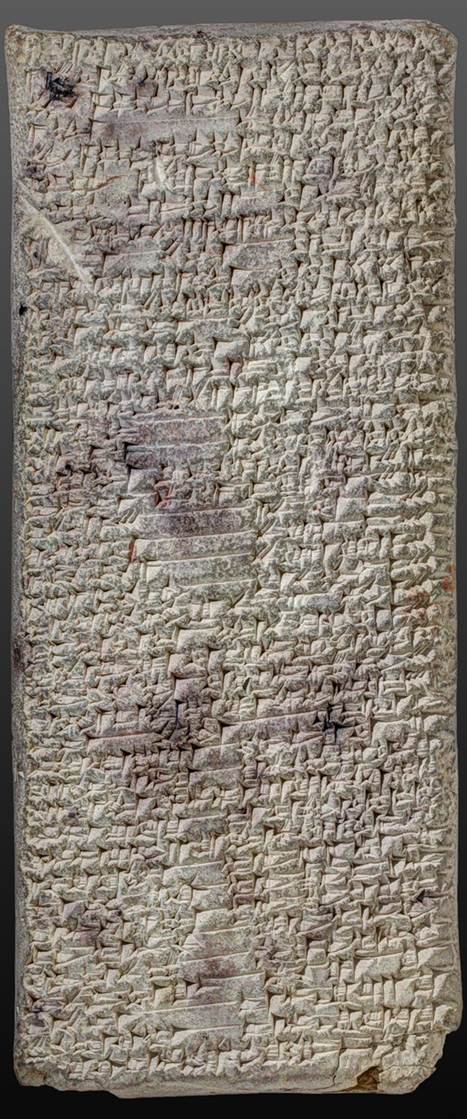

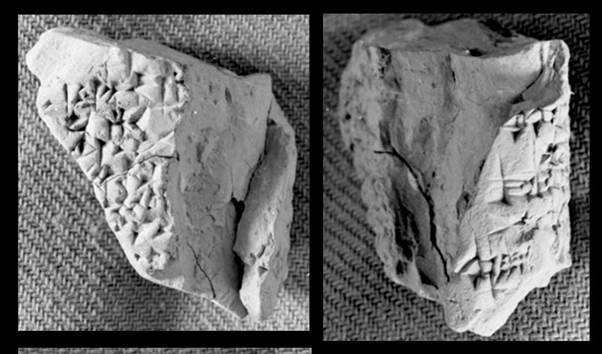

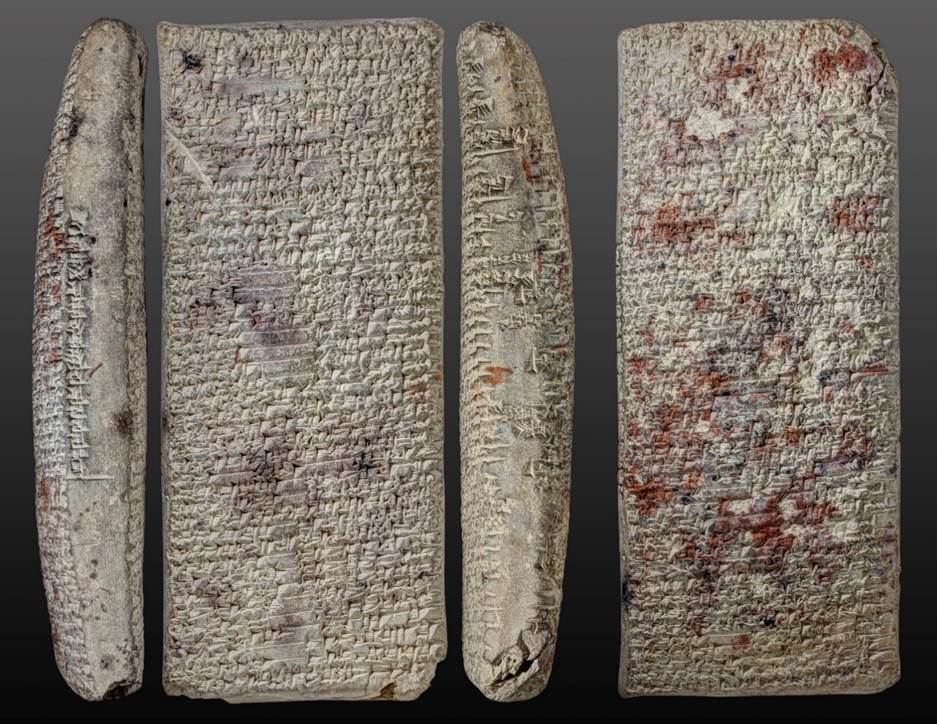

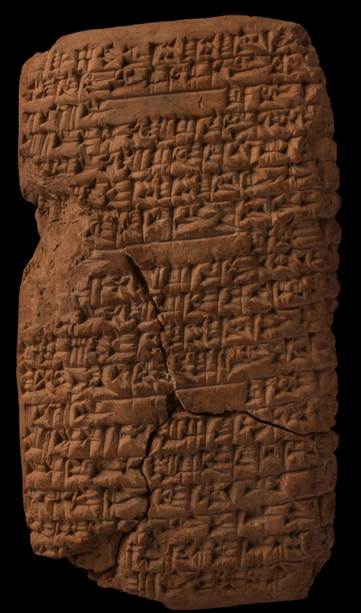

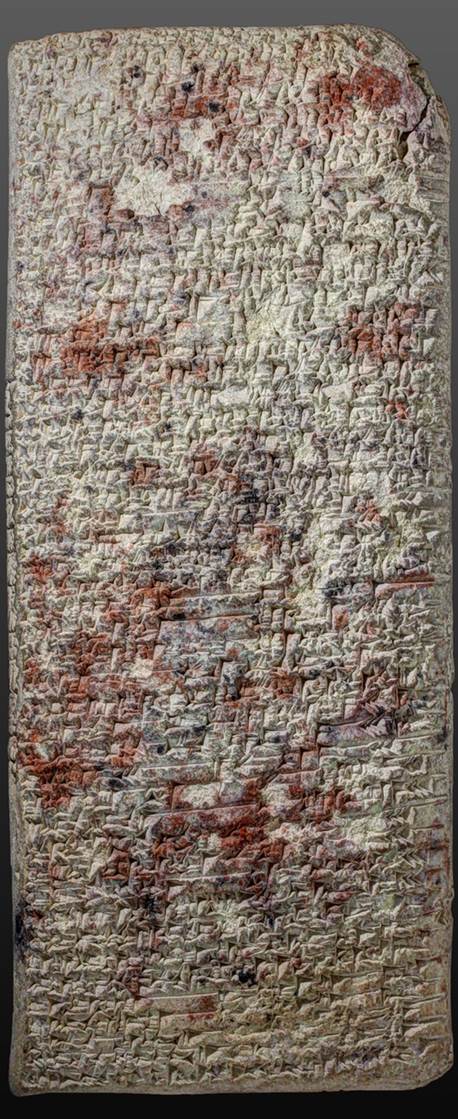

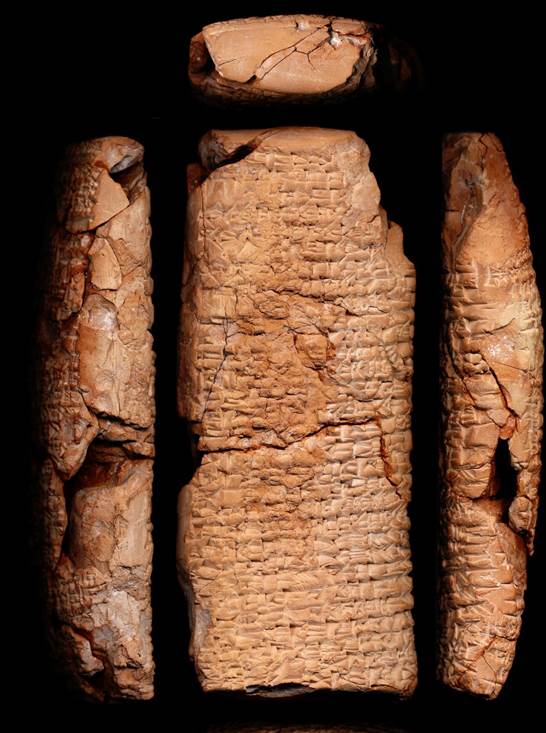

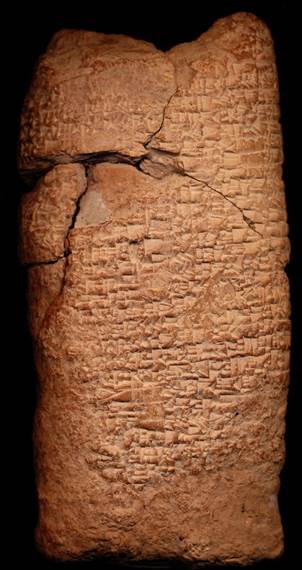

Figure 2.2. Artifact YPM

BC 018686 (formerly YBC 4621). Photograph of "YPM

BC 018686: Tablet. Inanna's Descent. Old Babylonian. Clay.," Yale Peabody

Museum of Natural History, Yale University, accessed May 2, 2019,

https://collections.peabody.yale.edu/search/Record/YPM-BC-018686. [The obverse,

reverse, left, and right sides of the tablet are shown]

It is important to highlight that the provenance—or historical origin—of an

artifact is an important component of its contribution toward a composition.

For the Nippur excavation tablets, geographic provenance was less of a concern

because the artifacts were discovered and documented during the same

expedition. However, Yale’s YBC 4621 tablet deserves mention because it has no

known or documented provenance.[52]

This means that scholars have almost no idea where it came from, the time

period it is from, and who created it. Like many historical artifacts, it was

likely acquired and purchased through an informal antiques dealer.[53]

The origin of the YBC 4621 tablet is doubly important because it provides text

that comes at critical plot points of ID.

More

expeditions were conducted in Iraq from 1922-1933 between Penn and the British

Museum, leading to further artifact discoveries containing snippets of ID.

These Ur excavations recovered many new artifacts and were directed by Sir

Charles Leonard Woolley (1880-1960),[54]

a British archaeologist.[55]

The expeditions were also accompanied by British historian Cyril J. Gadd

(1893-1969),[56]

the main person who copied the artifact contents so they could be published as

texts for other scholars to translate and interpret.[57]

Other institutions were also conducting expeditions during this time period.

From 1929-1937, the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute conducted

several excavations in neighboring regions of Nippur. These excavations,

alongside the ones at Ur, dug up most of the remaining artifacts required for a

full translation of all 412 lines of ID. A notable field Assyriologist for

Chicago’s Oriental Institute was Thorkild Peter Rudolph Jacobsen (1904-1993),[58]

a newcomer who would later lead the Oriental Institute and publish critical

translations and commentary of ID.

The

1920s were also important years for the composition and blueprint toward full

decipherment of ID. Chiera compiled and published sketches and notes on tablet

fragments that contained almost 275 lines of the total composition.

Additionally, he left valuable clues and details for the next generation of

Sumerian scholars interested in ID. Separate excavations in Iraq by leading

institutions like the British Museum (jointly with Penn) and the University of

Chicago collected thousands of artifacts containing snippets of ID. While many

of these artifacts would not be published as translations until as late as

1966, they were nonetheless in the hands of other scholars.[59]

In summary, by 1933, some thirty-five fragments utilized in the current ETCSL

translation of ID were at least discovered and awaiting translation.

Kramer’s First Wave

(1935-1951)

From

1935-1951, Samuel Noah Kramer (1897-1990)[60]

published a majority of the scholarship on ID, including some thirty books and

dozens of journal articles. His first comprehensive publication containing a

translation of ID was in 1937 and included 250 out of 412 usable lines,

roughly two-thirds of the myth.[62]

This translation primarily took advantage of the CBS 9800 tablet that was

previously identified by Chiera and Langdon, but not translated.[63]

Kramer evidently took a keen interest in ID because he “travelled to Istanbul

in 1937, and with the aid of a Guggenheim fellowship, devoted some twenty

months to the copying of one hundred and seventy tablets and fragments in the

Nippur collection of the [Ottoman] Museum of the Ancient Orient.”[64]

Like Chiera, Kramer explored the other half of the original Nippur

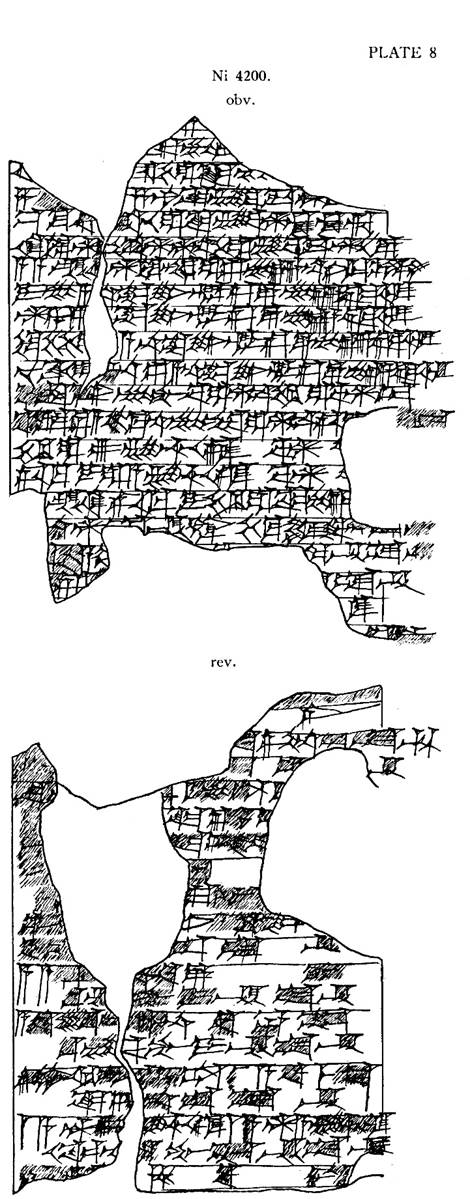

expeditions of the 1890s. These efforts paid off because Kramer spent the next

fifteen years publishing new versions of ID at a furious pace. In 1939, Kramer

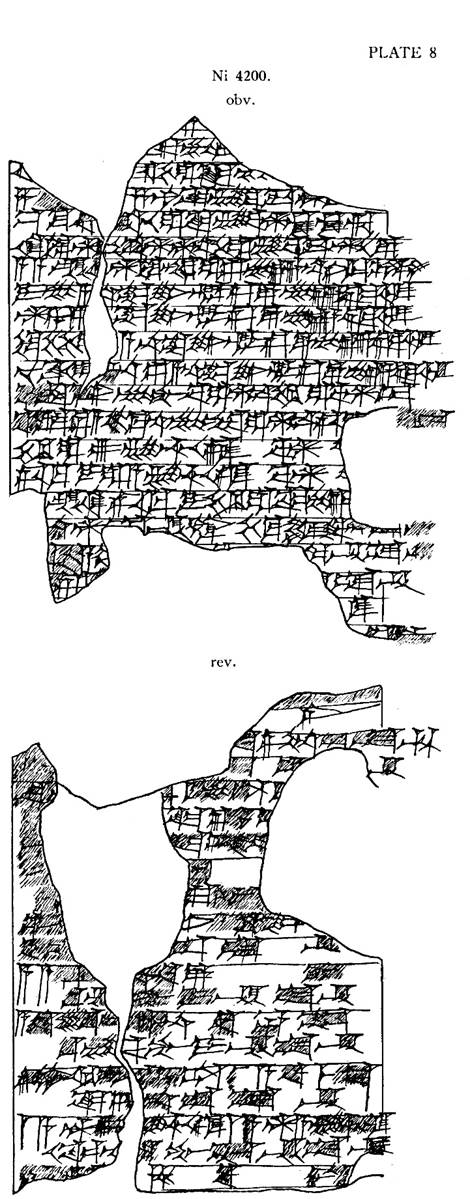

published a subsequent translation with the addition of tablets Ni 4200 and Ni

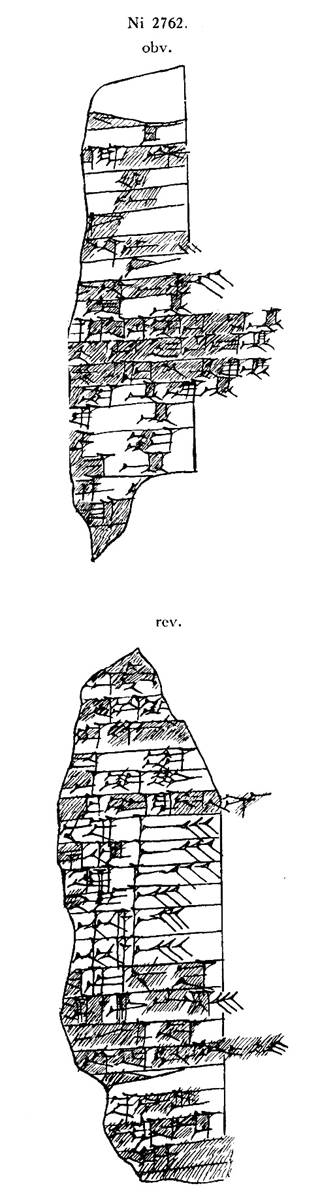

2762.[65]

These tablet additions resulted in a highly authoritative 1942 translation of

ID that contained roughly 270 out of 412 usable lines. With each version Kramer

published, key lines were refined, and new artifact additions were integrated

into the whole. Indeed, it’s also likely that Kramer’s translation skills

improved throughout the process.

Further

improvement, refinement, and translated material contributed to a strong

version of ID by Kramer in 1951. The early 1940s was a relatively tepid period

for ID scholarship because of World War II.[66]

After 1944, several translations emerged from various scholars that were based

on Kramer’s original 1937 framework. For instance, German Assyriologist Adam

Falkenstein (1906-1966)[67]

published a translation of ID in 1944. He was followed by a fellow German,

Friar Maurus Witzel (1882-1967),[68]

who published another translation in 1945.[69]

At this point, almost one-third of the lines were still missing from the

currently known 412. Scholars were aware of the previously mentioned Yale YBC

4621 tablet, but its 90 lines of text were yet to be translated. These efforts

culminated in Kramer’s 1951 publication of ID, which included the Yale tablet.

As later scholars have noted,[70]

Kramer’s 1951 publication proved to be the most authoritative (known as textus

receptus) version of its time.[71]

In total, Kramer published almost fifteen different updated translations of ID

from 1937 to 1951, making him the most decorated contributor during this time

period.

At

this juncture, it is important to note that Kramer’s translations during this

time period reflected revision-based activity toward the work of previous

scholars. Throughout these fourteen years, Kramer seemingly corrected mistakes

that Chiera[72]

and other scholars[73]

had made.[74]

Special mention of scholarly correction is important because it may represent

schism between pseudo schools of thought that each representative scholar may

have embodied in their interpretation of the artifacts and their contents.

Revision of previous scholars’ work may also represent the field’s collective

maturity and progress in artifact restoration methodologies. Revisions,

therefore, do not necessarily represent disagreement. Nonetheless, Kramer’s

authoritative 1951 version of ID included the use of fifteen sources (nineteen

artifact fragments) and a total line count of 344 out of 412.

New Artifacts and Commentary

(1952-1973)

The

1950s and early 1960s provided much-needed commentary, interpretation, and

analysis on Kramer’s 1951 version of ID. During this time period, several key

passages were improved upon, especially the last one hundred lines (which had

artifacts that would not be translated for another fifteen years). Witzel

published a commentary on Kramer’s work in 1952 that focused on the role of

Inanna’s husband and his fate—the ending.[75]

Falkenstein also provided important commentary on Kramer’s work: “In the same

year [1952] Falkenstein read a paper at the third Re[n]contre Assyriologique

Internationale in which he discussed ID.”[76]

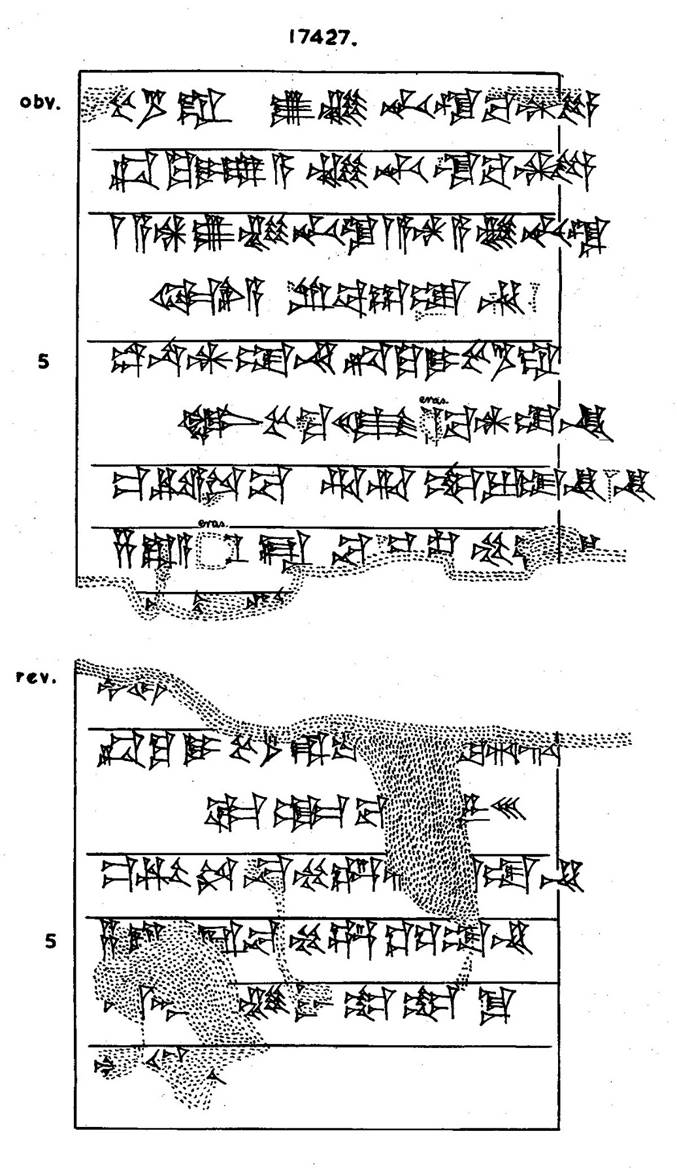

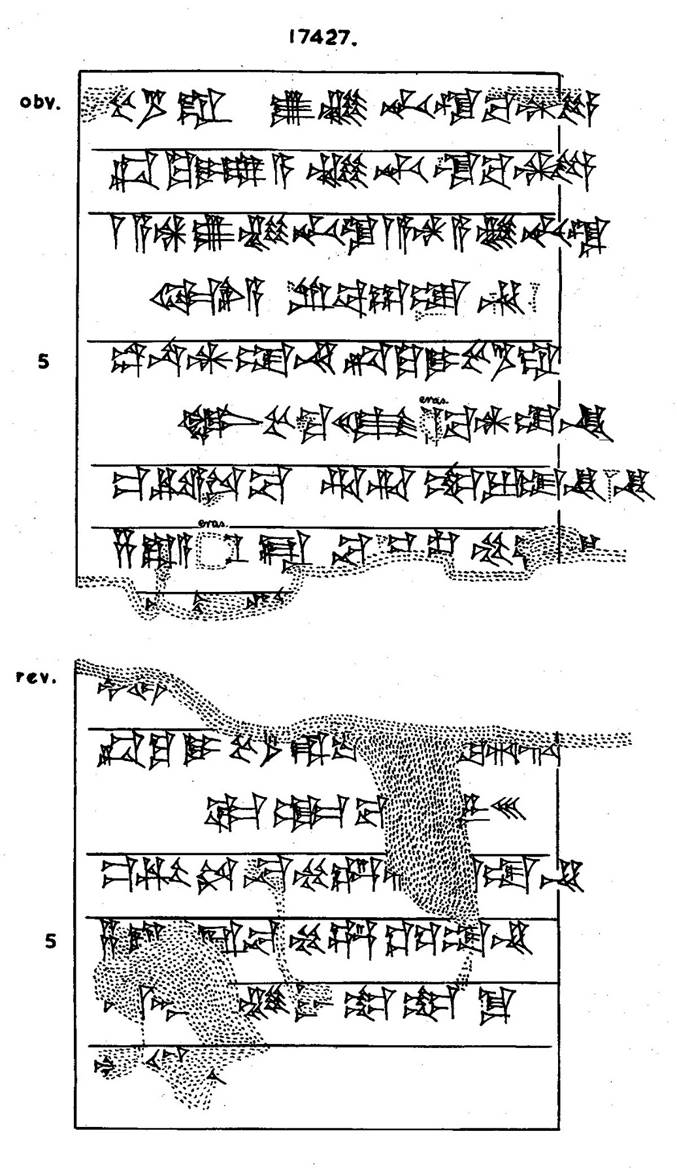

A new, albeit small, fragment named BM 17427 was also added in 1959 by H. H.

Figulla as a result of his publication of the tablets discovered in Ur some

thirty years earlier.[77]

Significantly more authorship related to ID occurred in the 1950s by the likes

of Jacobsen and Ferris J. Stephens (1893-1969),[78]

Kramer and Inez Bernhardt in 1962, and Benno Landsberger in 1960. Through 1963,

these aforementioned scholars refined key passages of ID so that they made

sense from a peer-reviewed perspective. There is no doubt that deciphering ID

was a team effort. Almost every reputable translation of ID—whether print,

digital journal, or blog—cites artifact or translation publications from the

scholars previously mentioned, primarily the big five.[79]

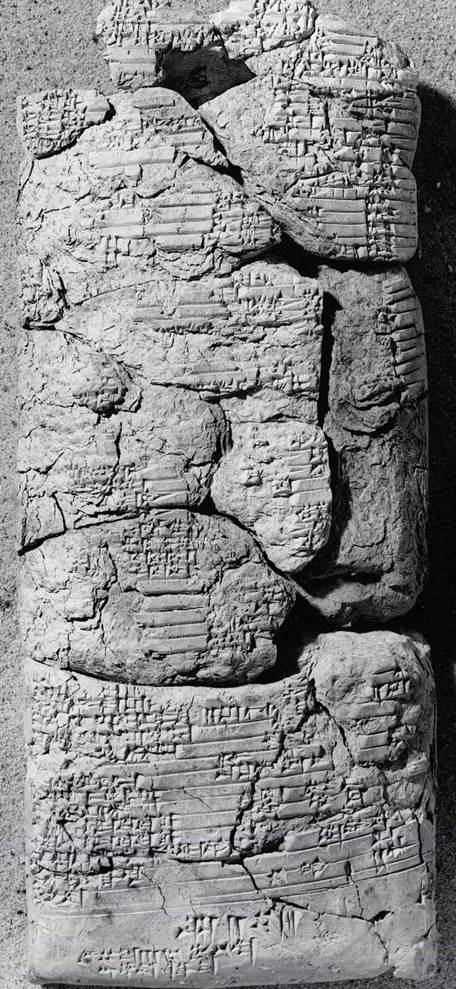

1963

was an important year for compiling the whole story with the addition of newly

translated artifacts from the Ur excavations done by Woolley in the 1920s and

1930s. In 1963, Kramer and Gadd published translations of several artifacts

collectively grouped as belonging to the Ur Excavation Texts [volume 6,

number 1] (UET VI) series: UET VI 8, 9, and 10.[80]

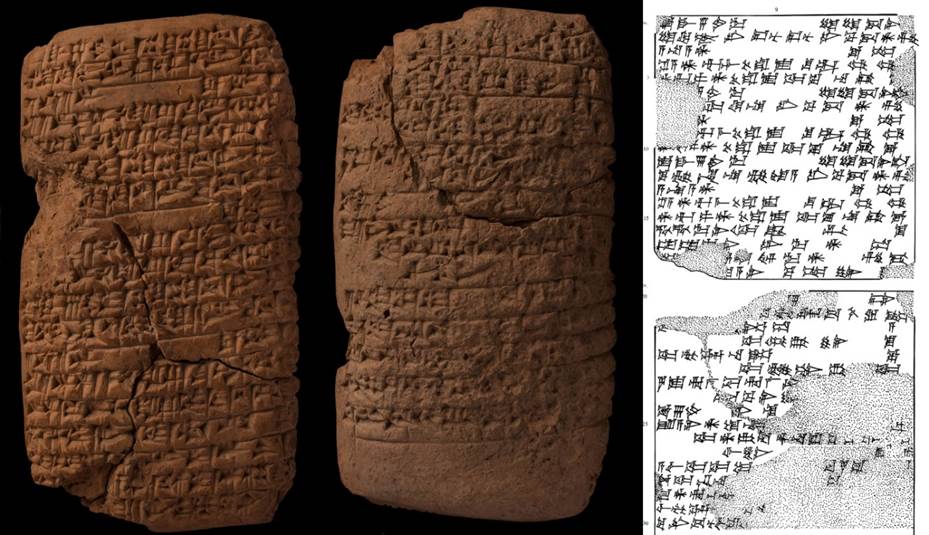

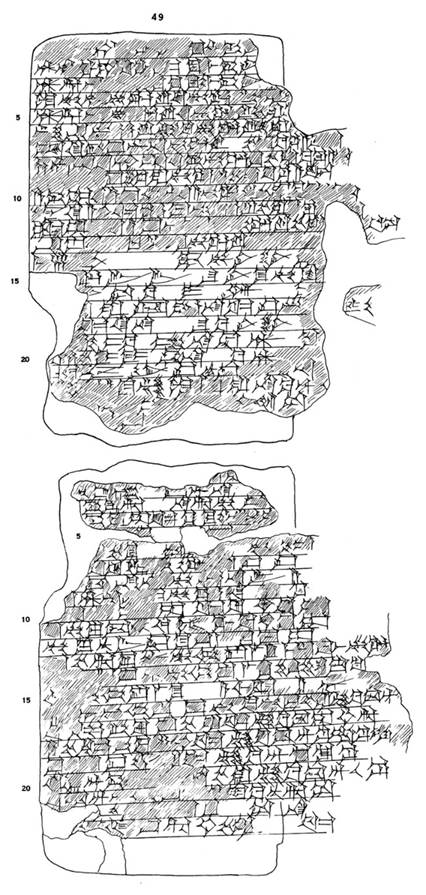

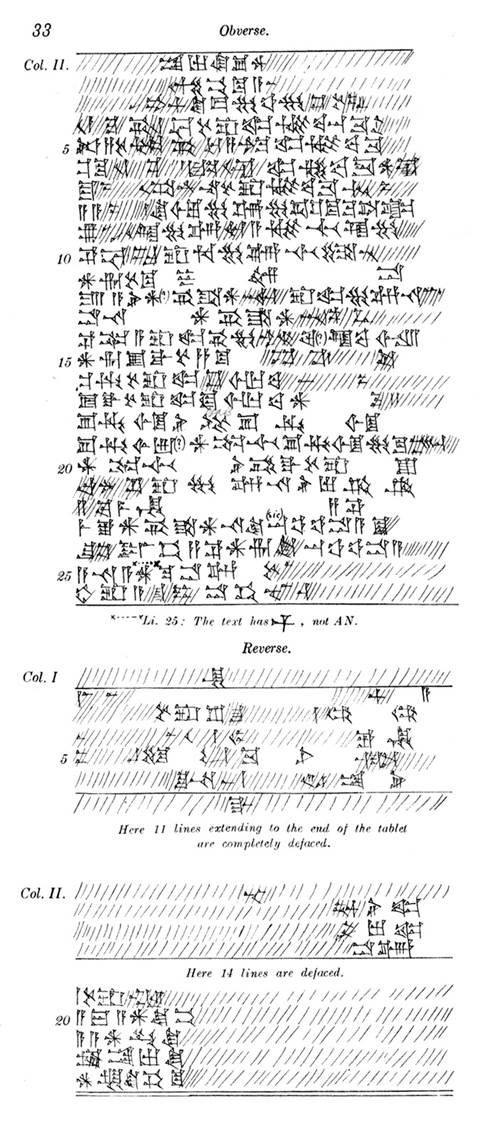

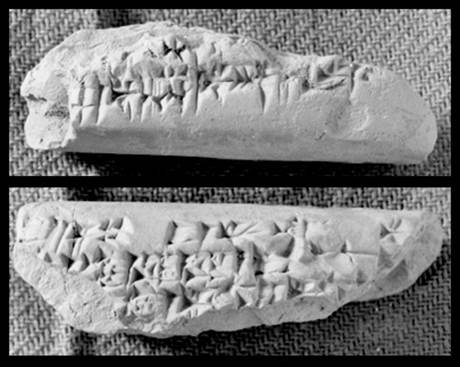

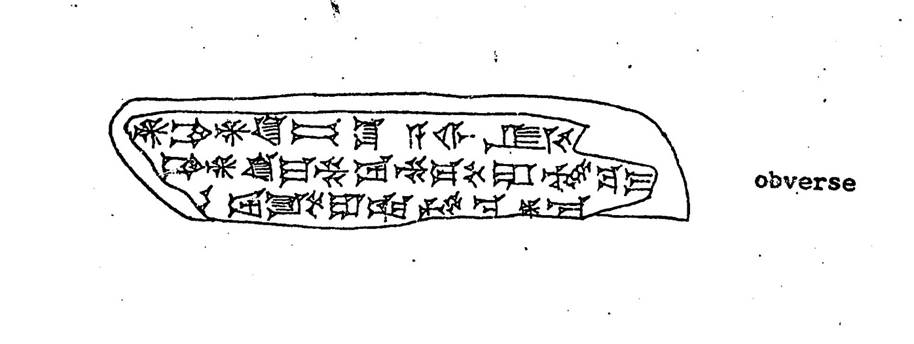

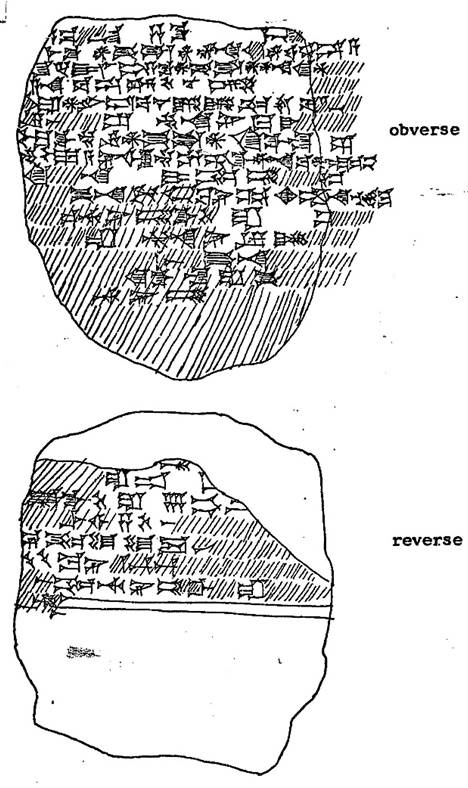

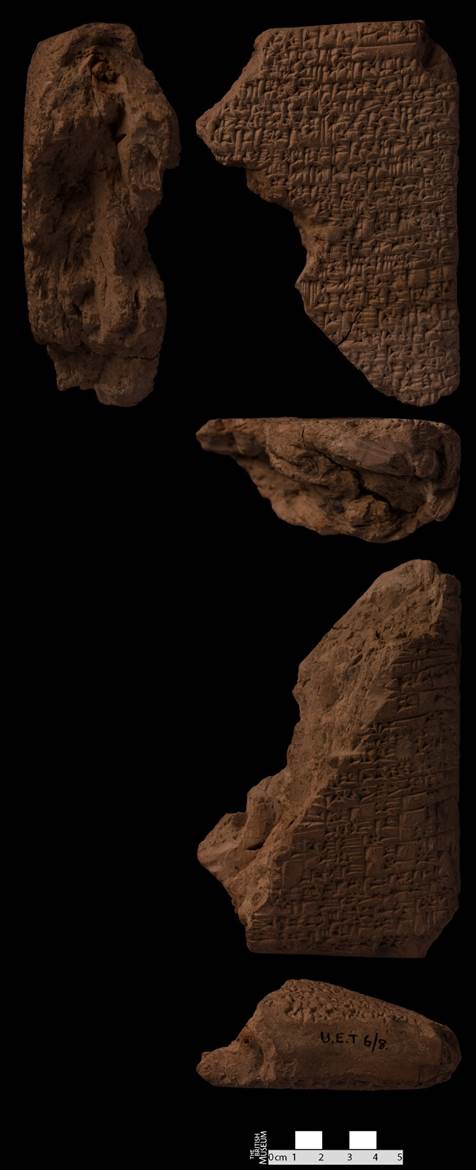

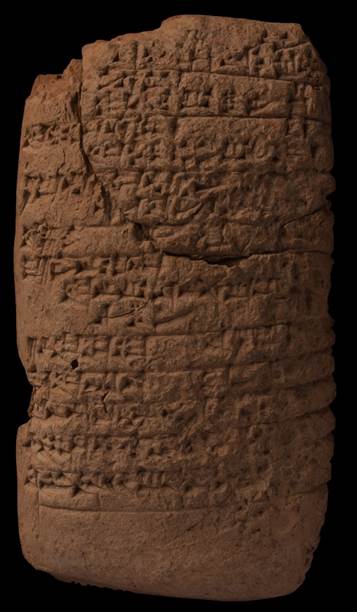

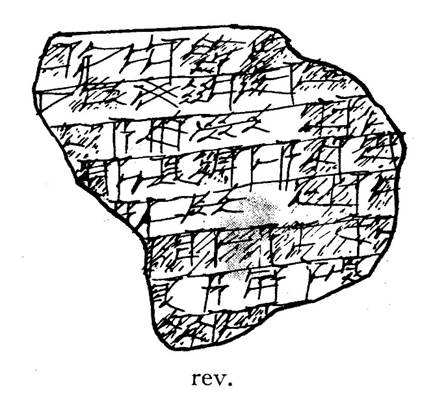

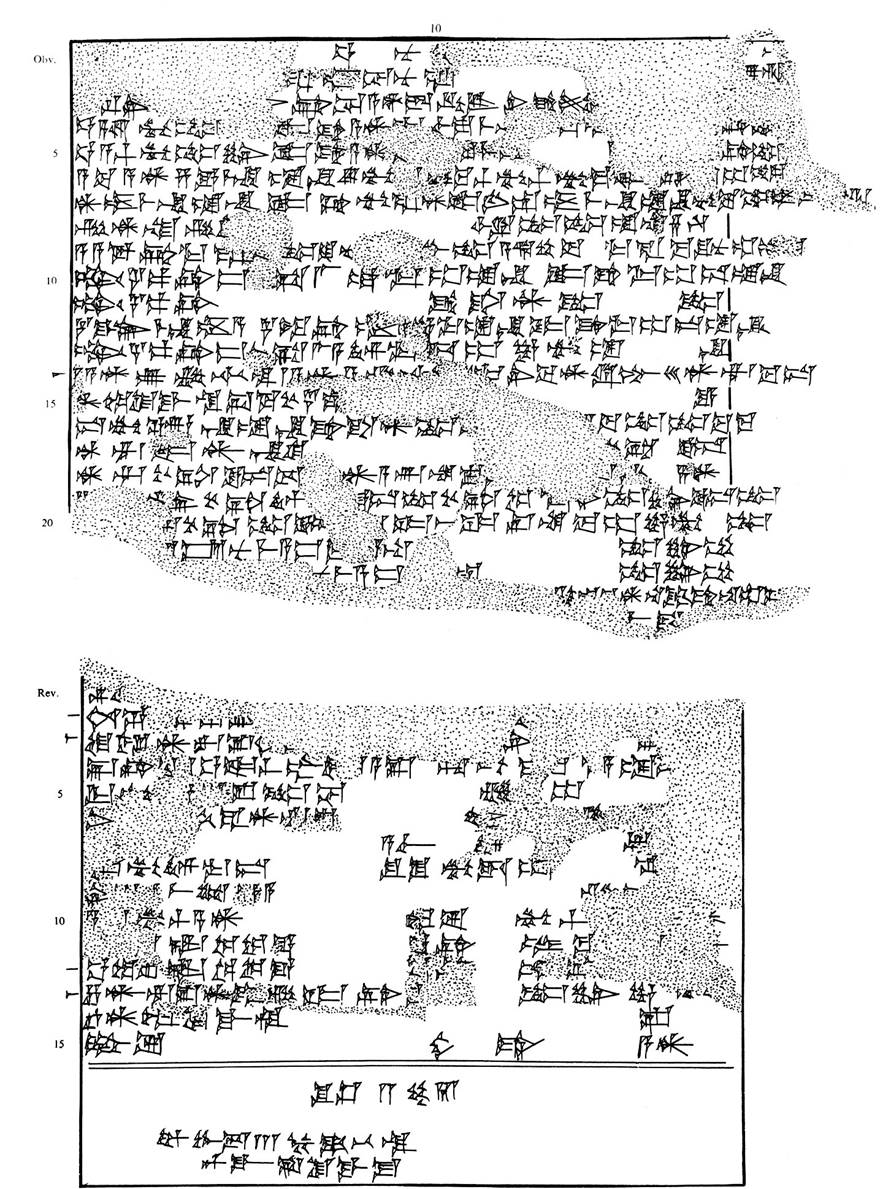

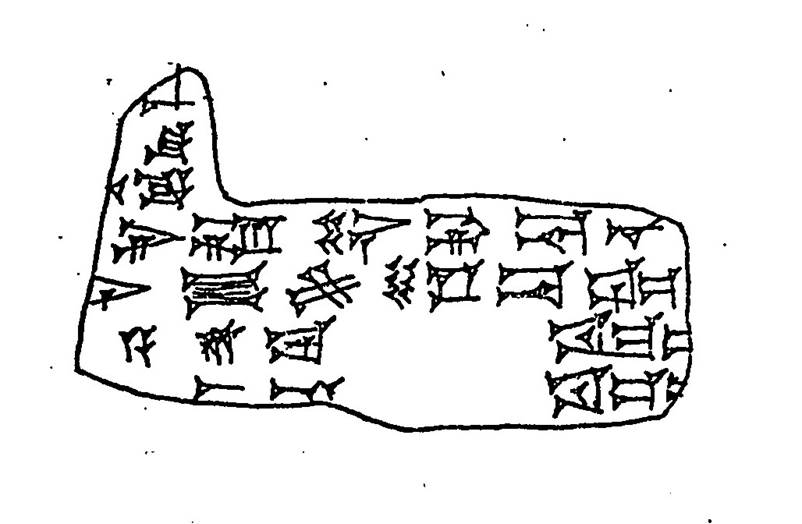

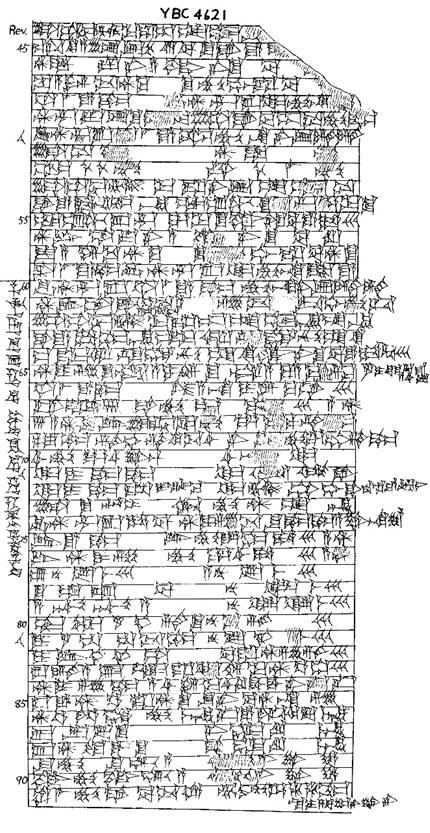

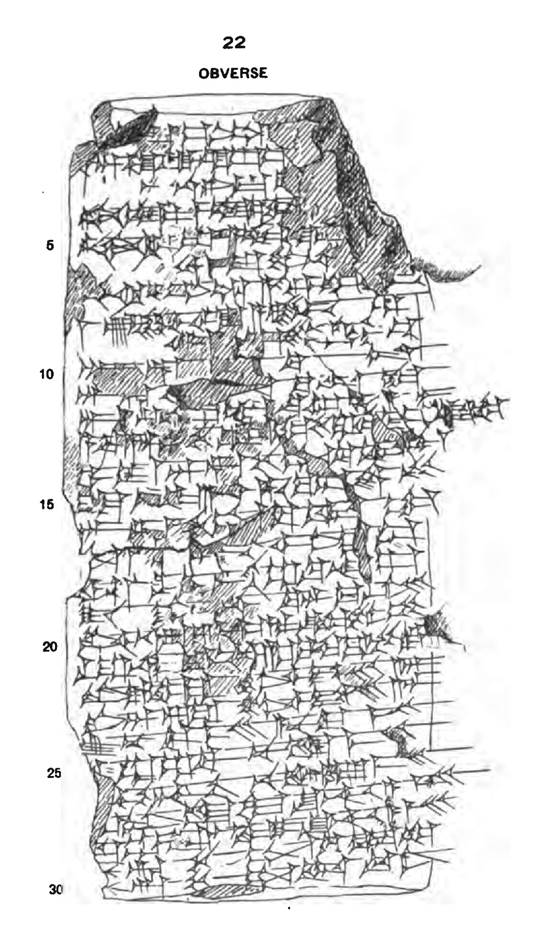

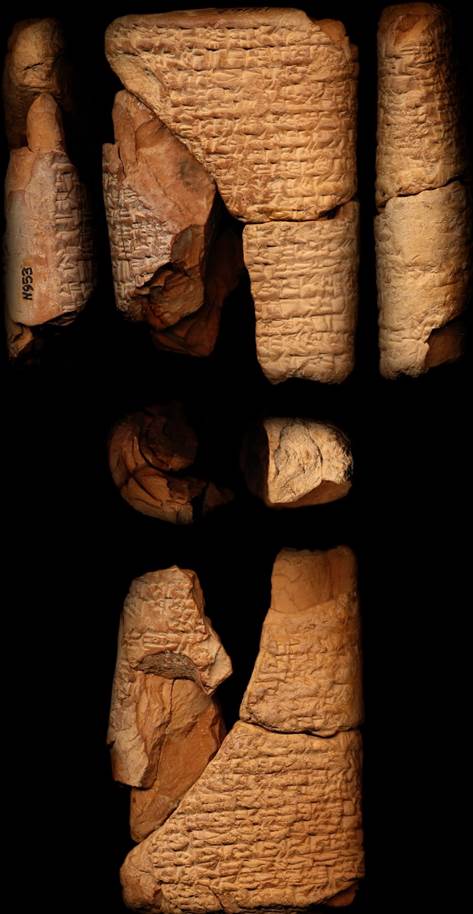

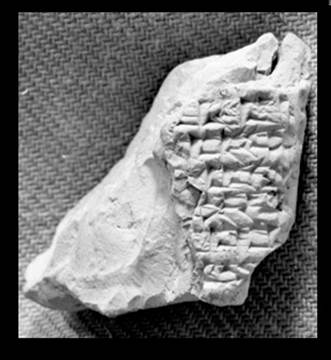

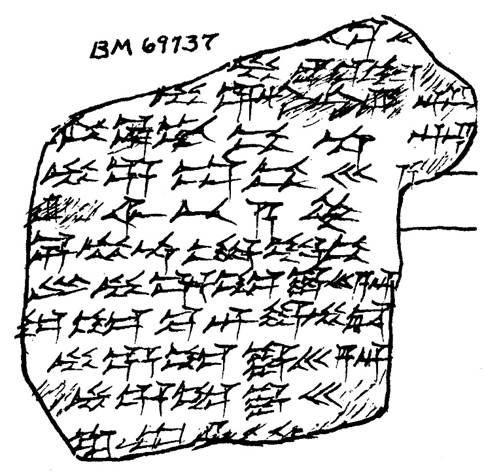

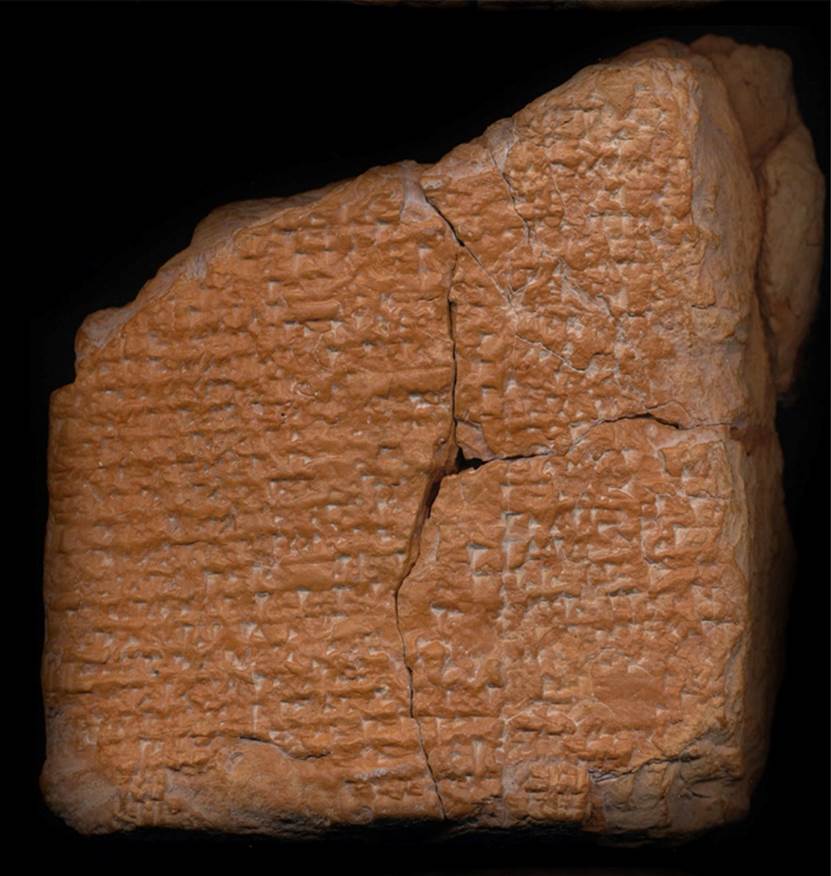

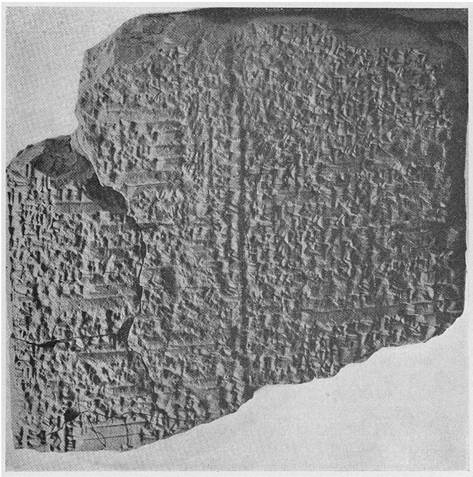

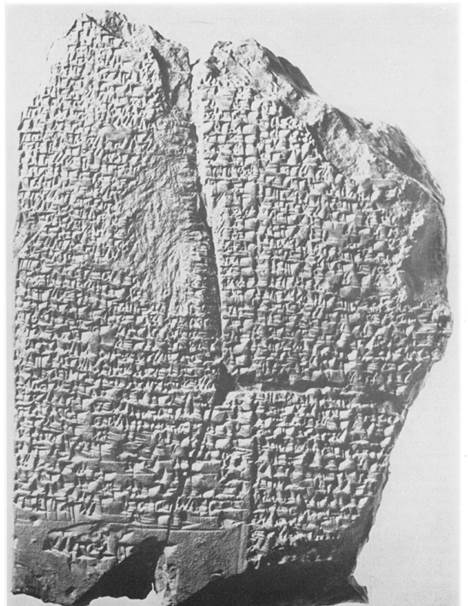

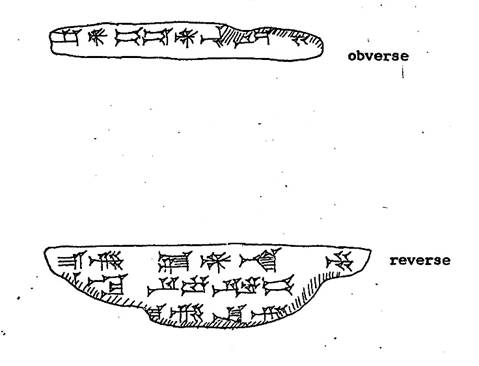

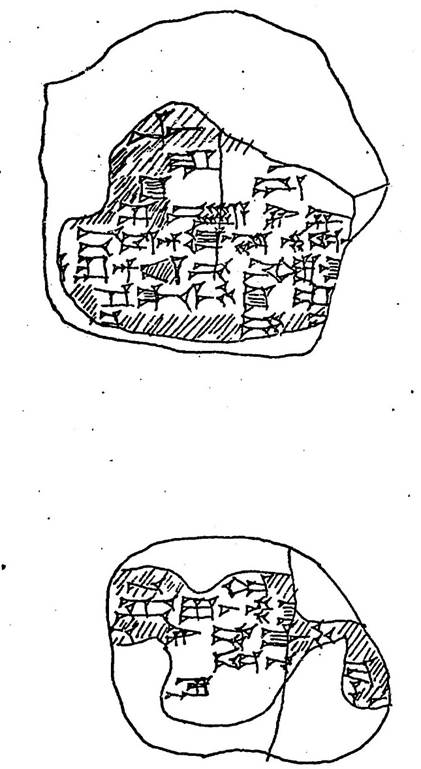

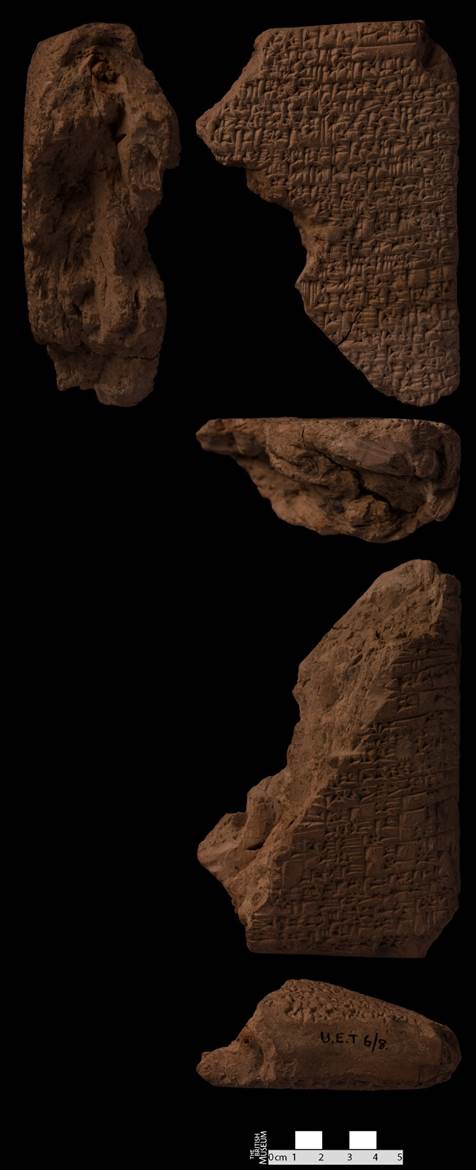

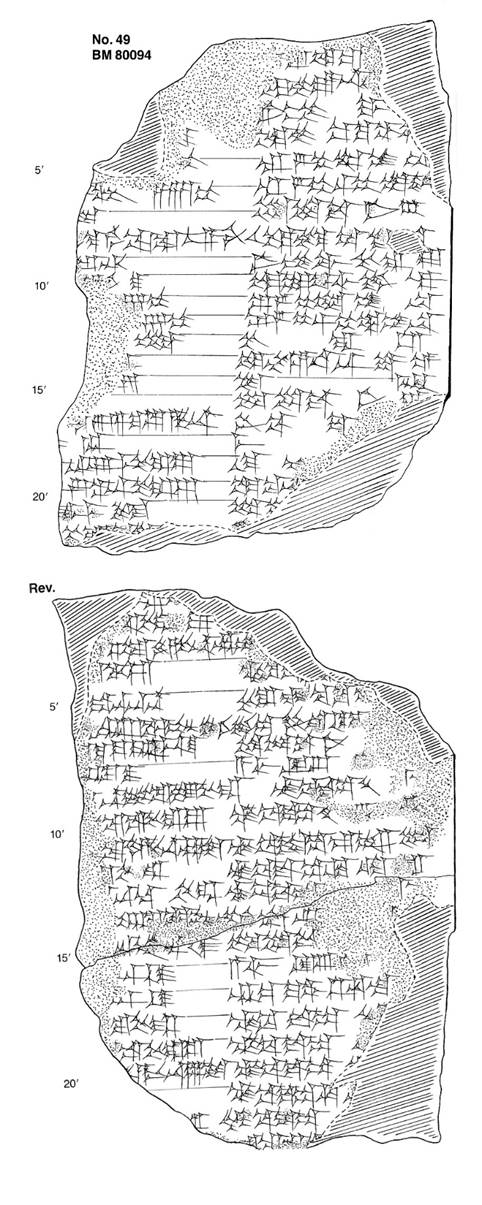

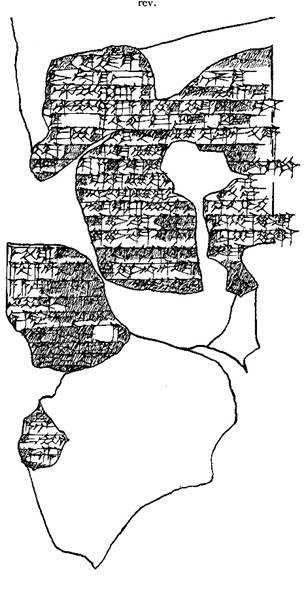

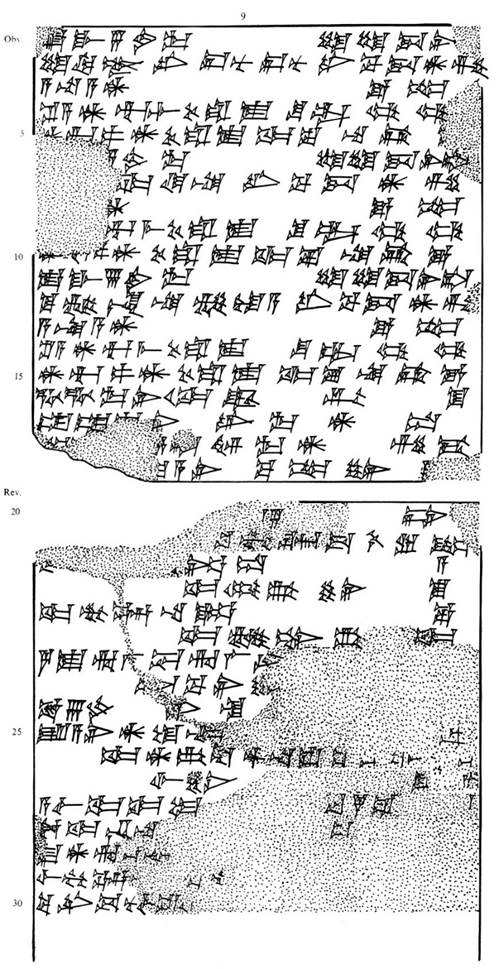

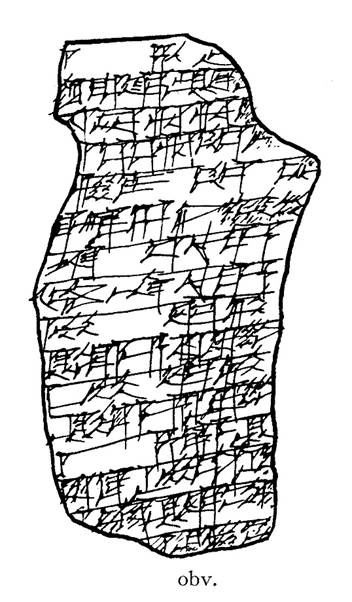

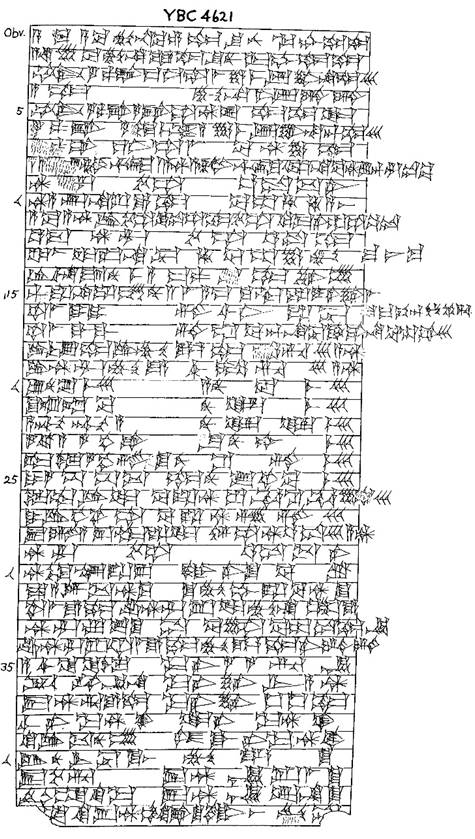

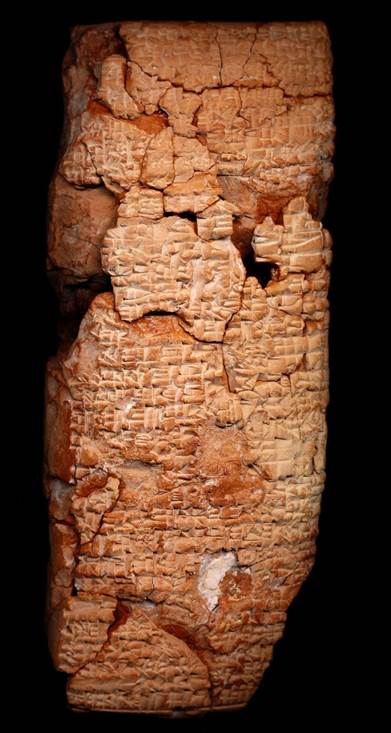

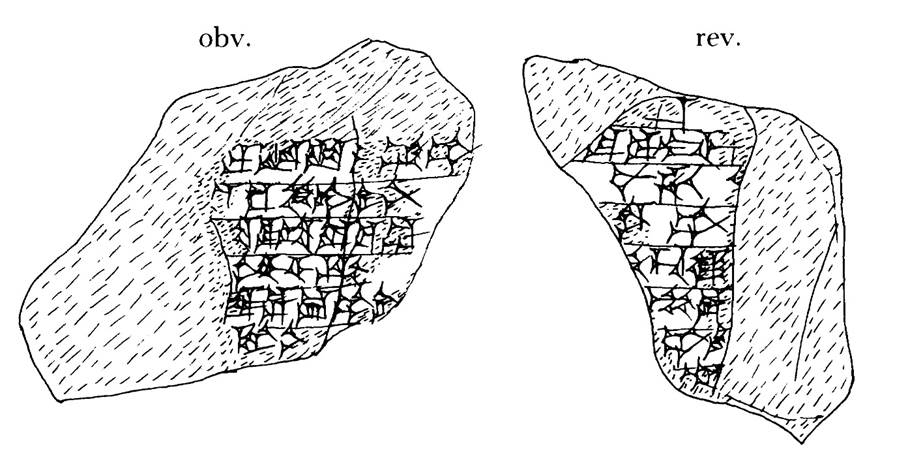

Figure 2.3. Artifact UET

VI 9 (6/1 9). Photograph and sketch of "Archival

view of P346094," Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (CDLI), University

of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), accessed May 1, 2019,

https://cdli.ucla.edu/search/archival_view.php?ObjectID= P346094.

[Obverse and reverse tablet orientations]

The importance of

these three unusually wide tablet artifacts cannot be understated as they

provided over 160 lines of translated text during key plot points. More

importantly, the contents included clues about a new ending that other scholars

had debated for roughly twenty years.[81]

The main concern was what happened to Inanna’s husband, Dumuzi, at the end of

the story.

These new findings prompted Kramer to publish several new artifact translations

as well as a critical 1966 update to his previous version of ID.[83]

The remainder of the 1960s and early 1970s saw Kramer publish many minor

updates in what we can call his second wave. The new UET series artifacts would

later result in seventy new translated lines of ID, moving the total usable

line count to roughly 360 (still fifty-two lines short of the ETCSL version).

Concurrently,

Jacobsen and others began assimilating unique interpretations into their

translations of ID, differing significantly from Kramer’s canonical texts.

While Kramer and other scholars were publishing translations in the mid to late

1950s, Jacobsen was conducting further excavation work in central and southern

Iraq (formerly Ur of Sumer)[84]

with Robert McCormick Adams Jr. (1926-2018).[85]

Notably, Jacobsen and Adams were documenting canals and the impact of

irrigation flooding on ancient Sumerian peoples.[86]

These unique hands-on experiences in modern-day Iraq may have impacted

Jacobsen’s perspectives of Sumer and ID. By the 1960s, it was clear that

Jacobsen and Kramer had different interpretations, despite co-authoring a paper

as early as 1953.[87]

For instance, Jacobsen notably began replacing the word netherworld with

Hades—a known Greek term for the underworld.[88]

Additional scholarship and artifact assignment took place in the 1960s via

Bendt Alster (covered more prominently later), Falkenstein,[89]

and several new individuals like Muazzez Çig[90]

and Miguel Civil.[91]

Kramer contributed toward the identification of artifacts mentioned by these

scholars as well. By now, we can clearly see the amount of complex coordination

required for these scholars to work together—all in an age without the

internet, no less. By 1972, Kramer’s authoritative version of ID included

twenty-nine artifacts (fourteen new ones from the previous 1951 period) and

increased the total coherent line count from 250 to roughly 360. The main

problem that remained was the crucial missing gap of lines at the end of the

poem (lines 380-412).

The First Semi-Complete Translation

(1974-1996)

Between

1974 and 1996, several prominent ID scholars passed away, and new individuals

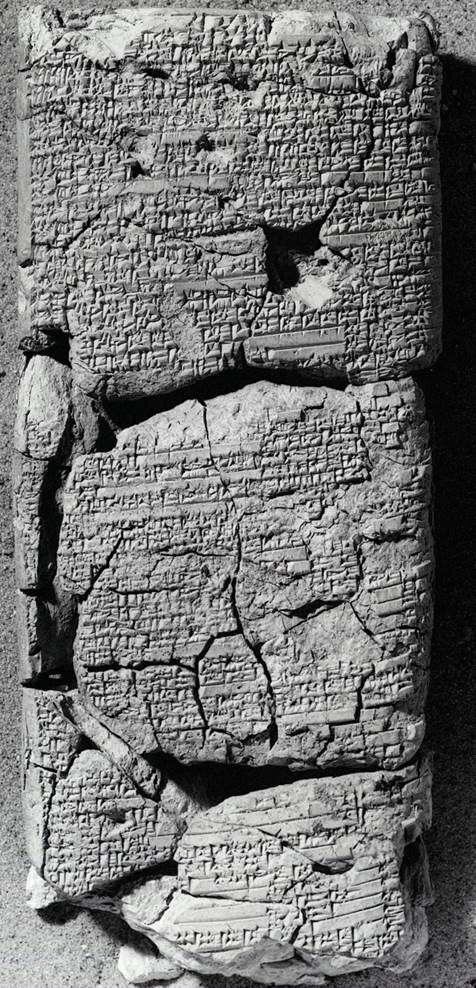

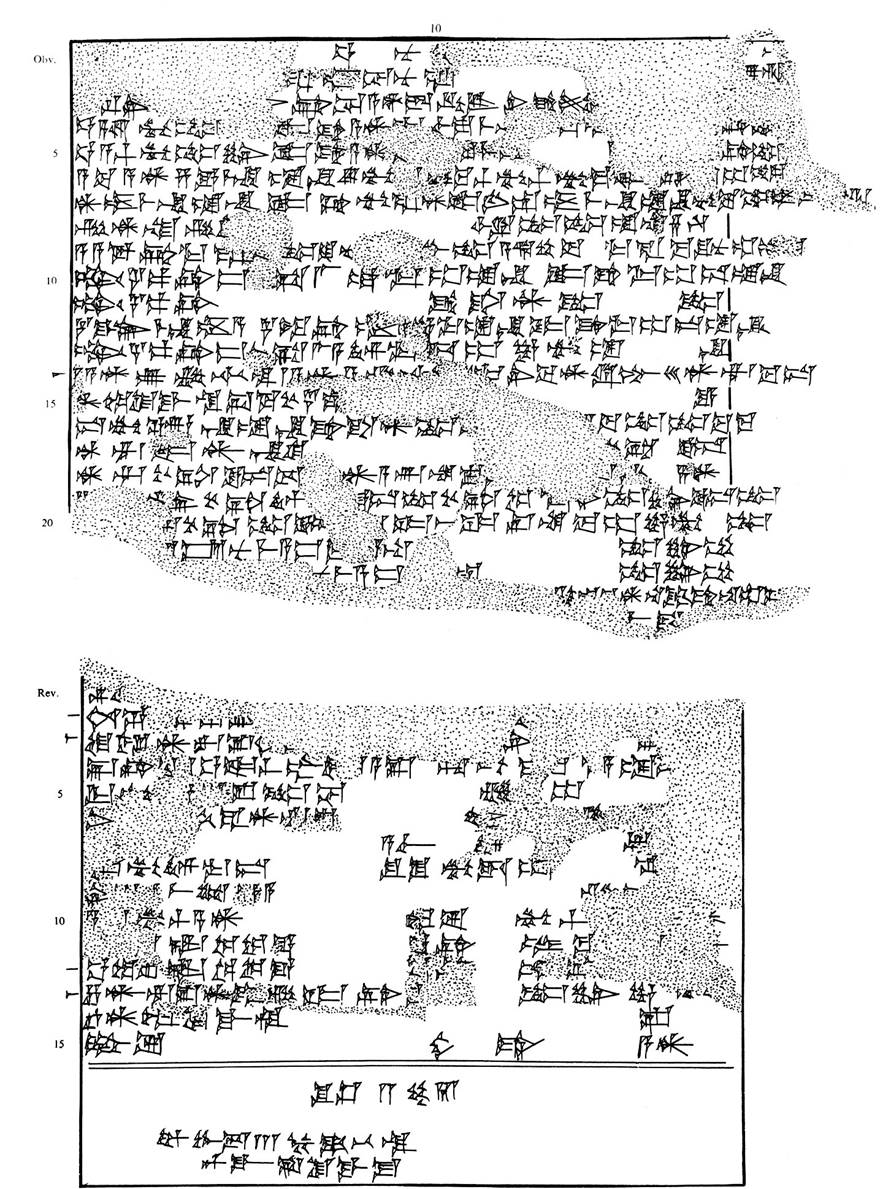

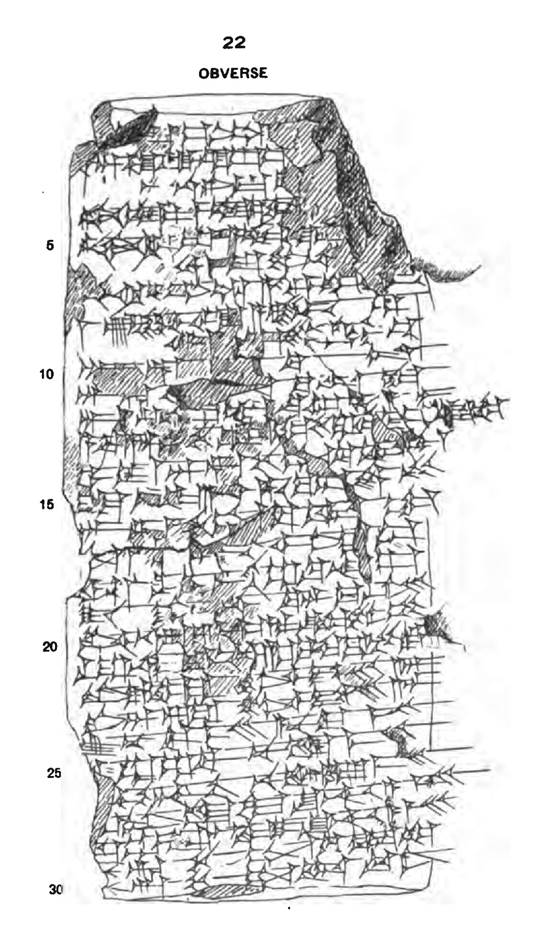

built upon their work to compile a semi-complete translation. The first and

most notable of these new scholars was William R. Sladek Jr. (1938-1993),[92]

who in 1974 published a 300-page PhD dissertation (in philosophy) at the Johns

Hopkins University. He appropriately titled his dissertation “Inanna's Descent

to the Netherworld.”[93]

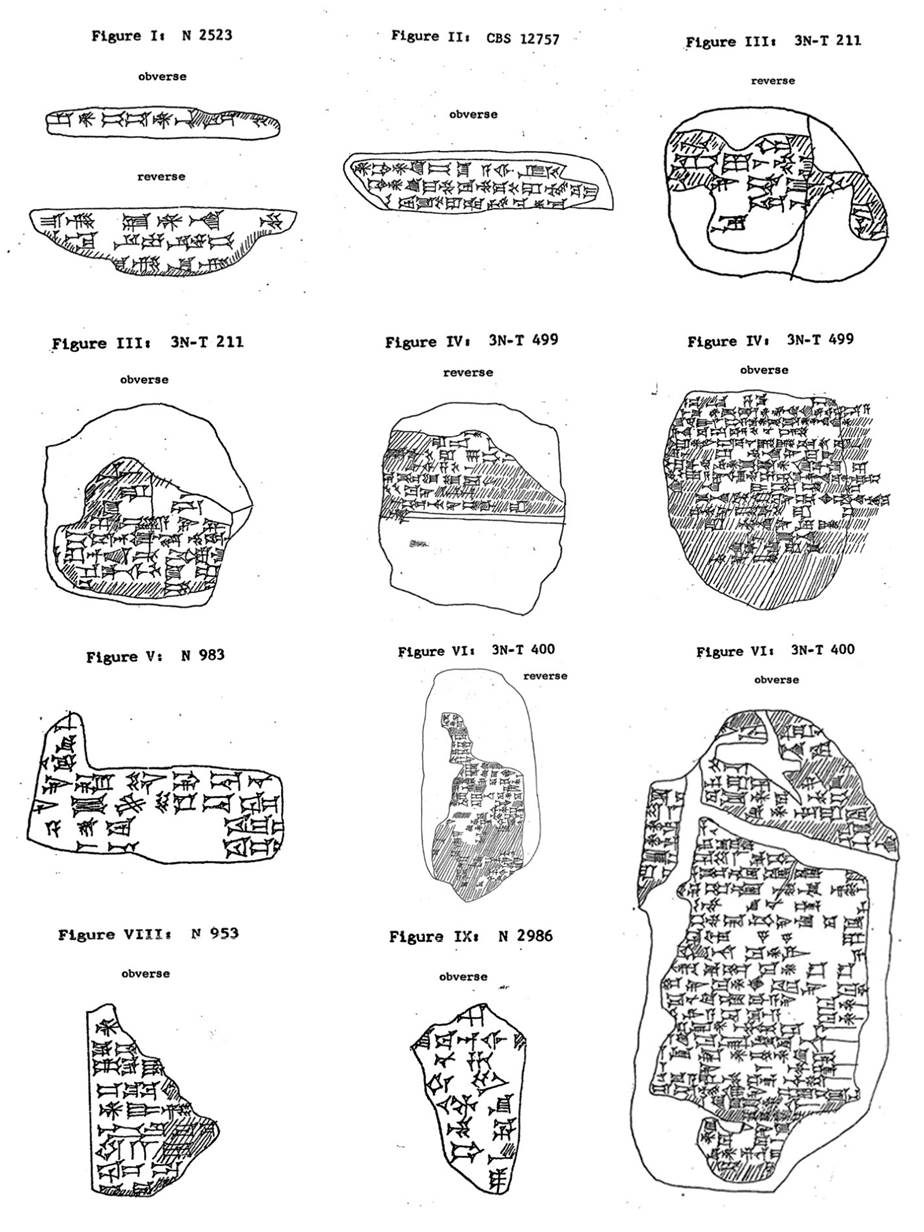

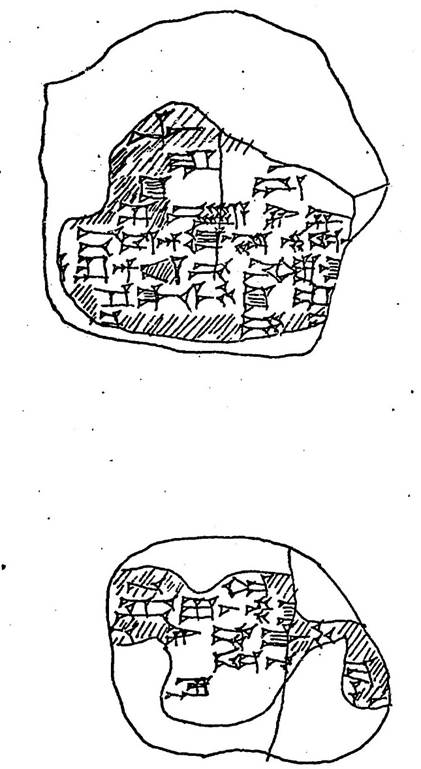

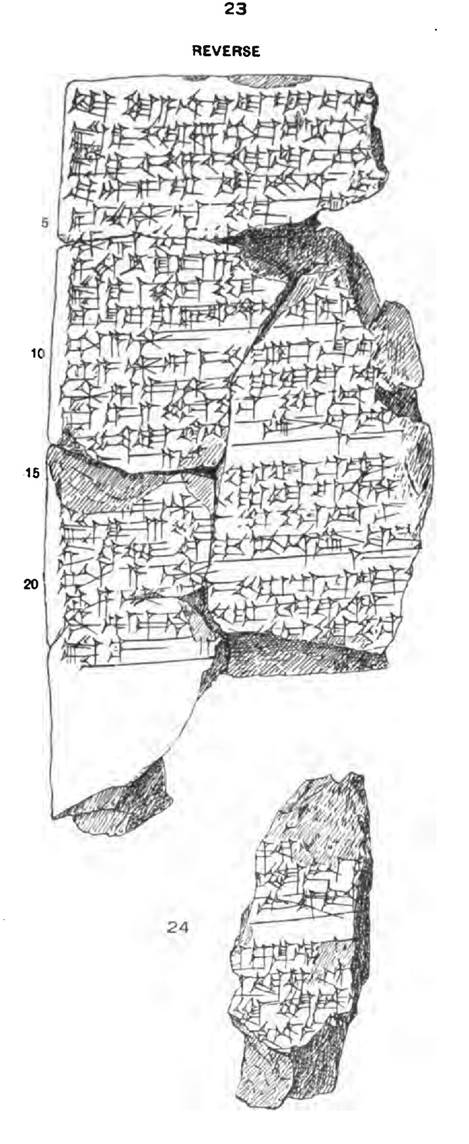

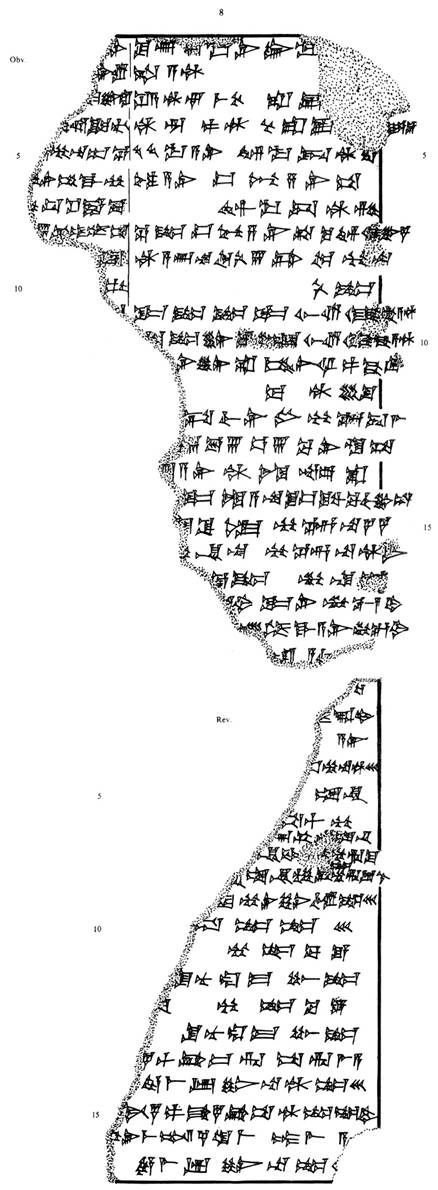

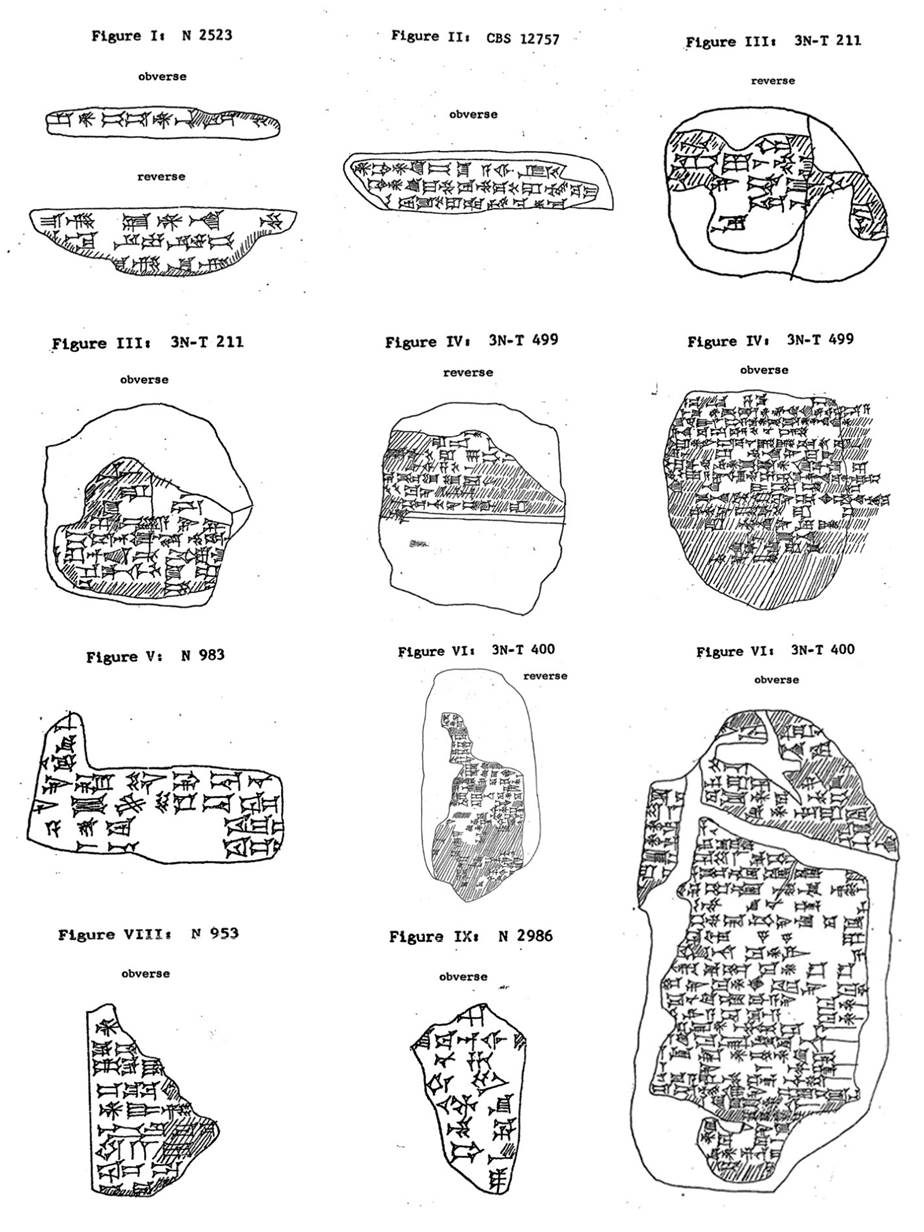

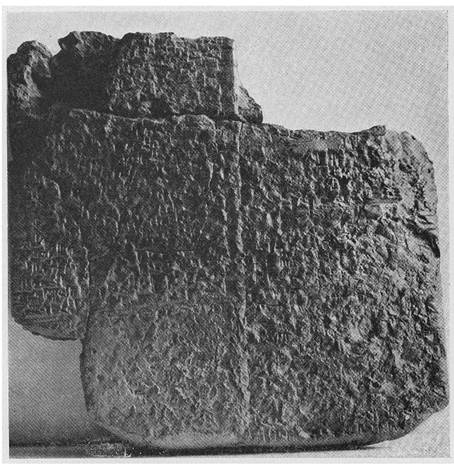

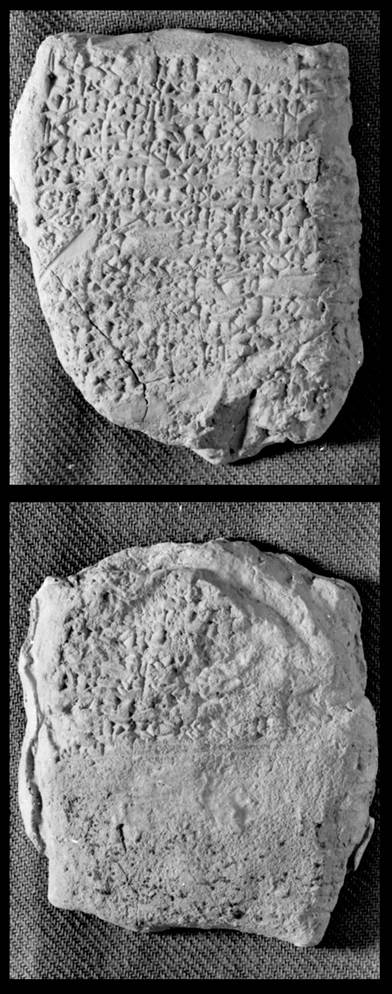

Sladek deserves special recognition in the chronology of ID for three reasons.

First, his addition of almost ten critical artifact translations resulted in

the most complete version of ID of his time. Sladek’s artifact translation

contributions represent almost 10 percent of all the artifacts in the ETCSL

version of ID; moreover, his dissertation still receives generous citations

among other ID scholars. Second, Sladek’s work was (and still is) well-regarded

by cuneiformists and ID scholars alike—indeed, even Kramer formally approved of

Sladek’s work.[94]

Finally, the present survey would not have been possible without Sladek’s

robust documentation. Sladek’s dissertation included sketches, translations,

and transliterations of almost all remaining lines of ID with the use of seven

previously untranslated artifacts: N 2523, CBS 12757, 3N-T 211, 3N-T 499, N

983, 3N-T 400, and N 2986. His published version of ID contained 386 usable

lines that clarified the obscure meanings Kramer and other scholars wrestled

with for the past fifty years. Finally, Sladek’s version introduced the line

count of 412, the authoritative total still in use today in the ETCSL version.

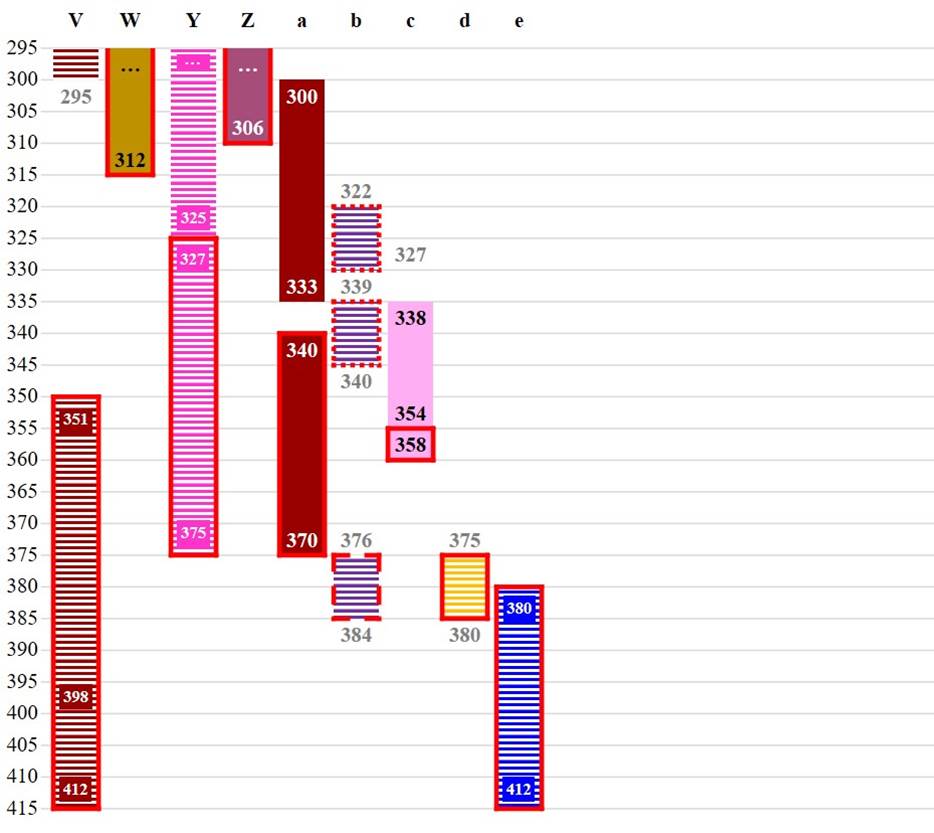

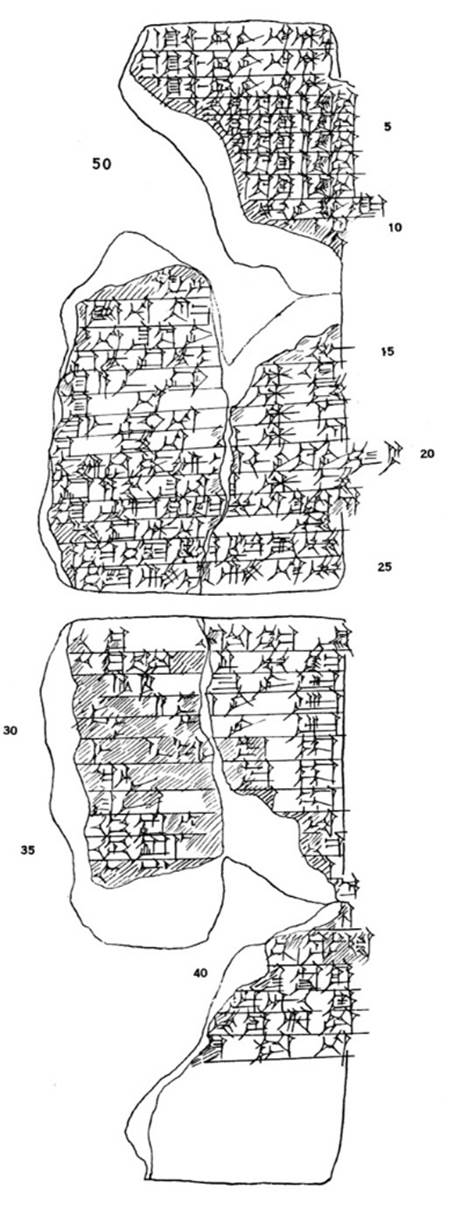

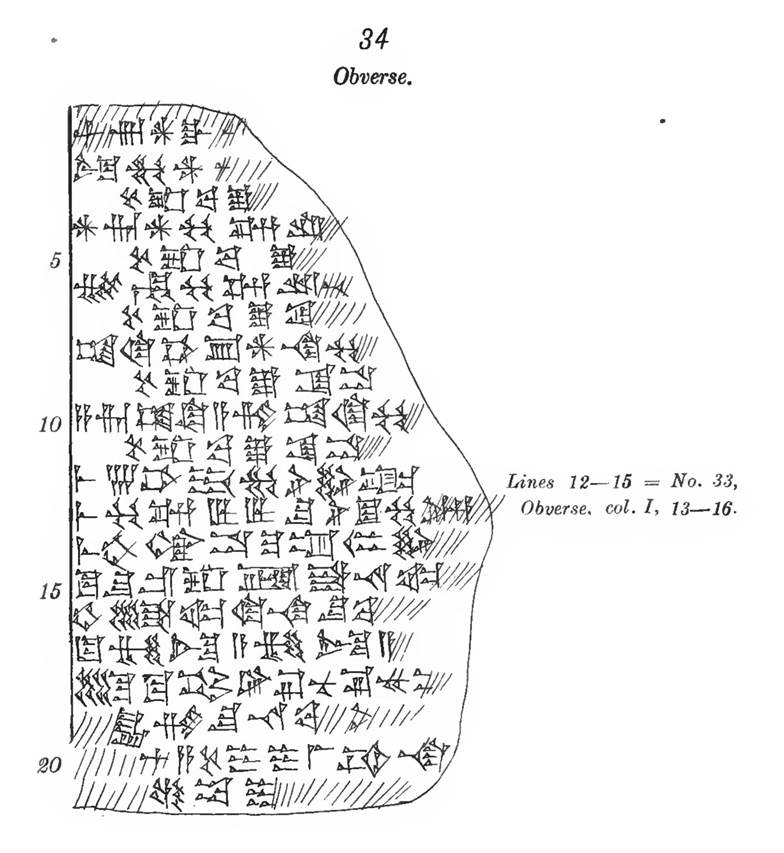

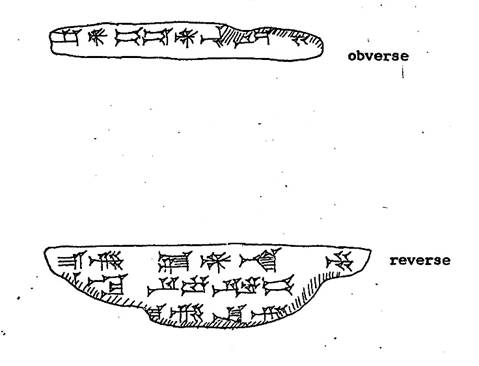

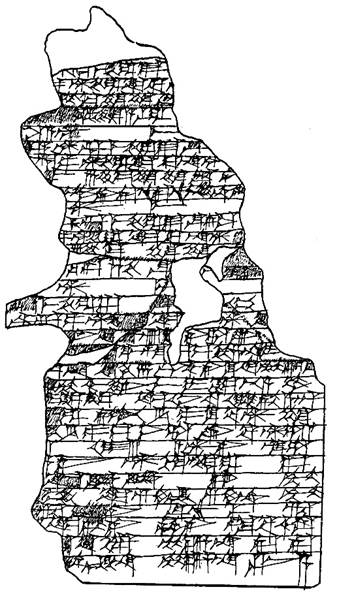

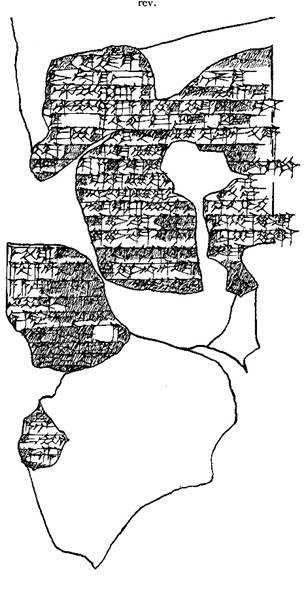

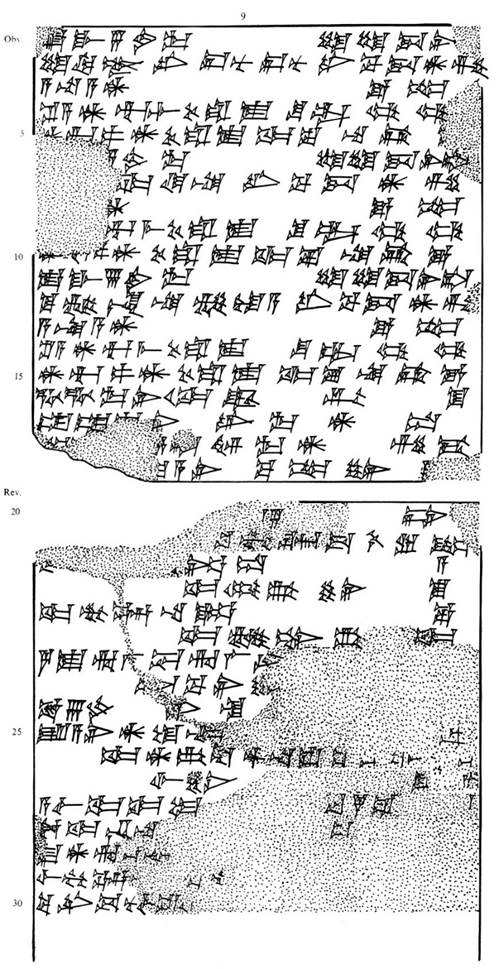

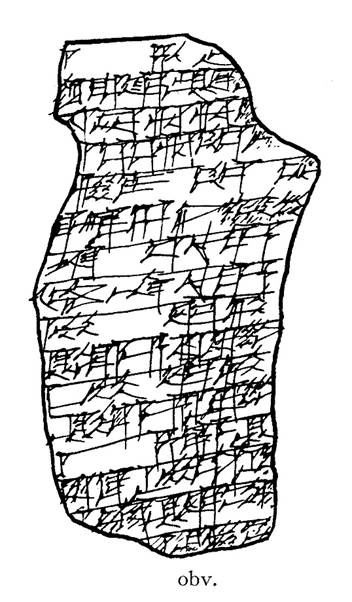

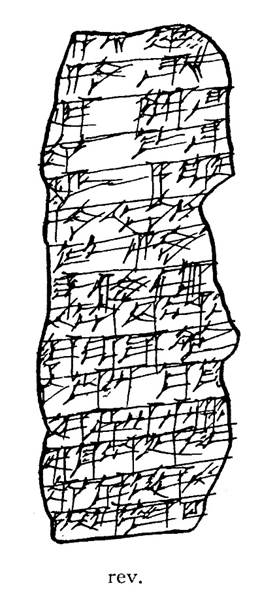

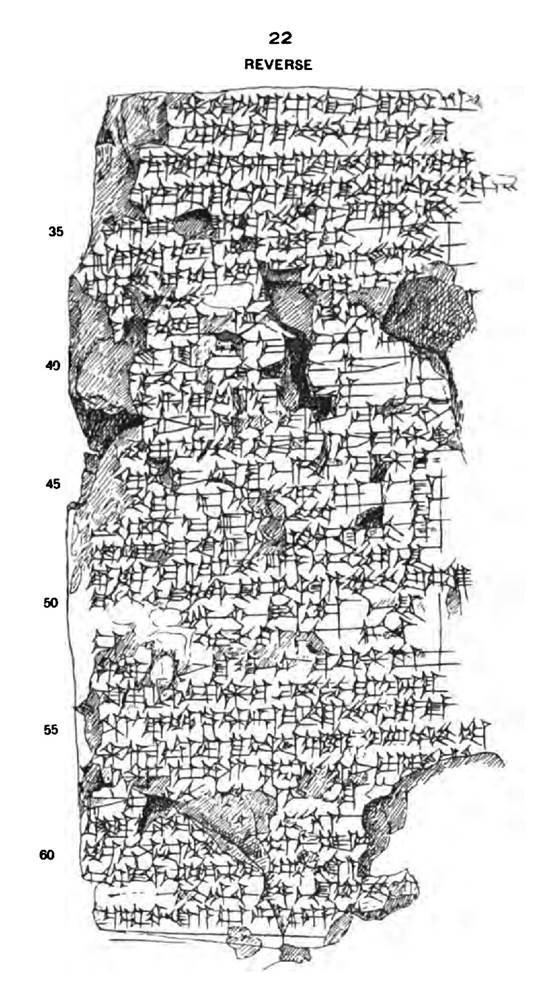

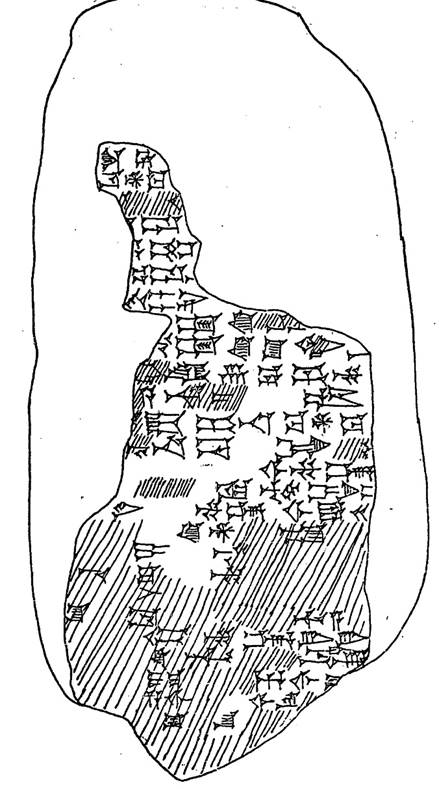

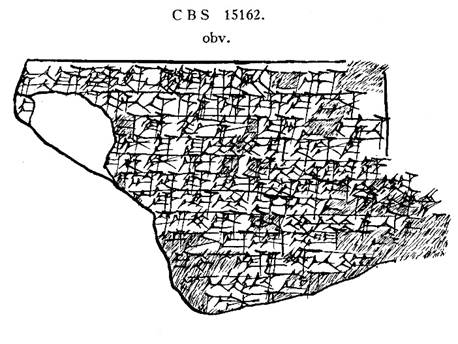

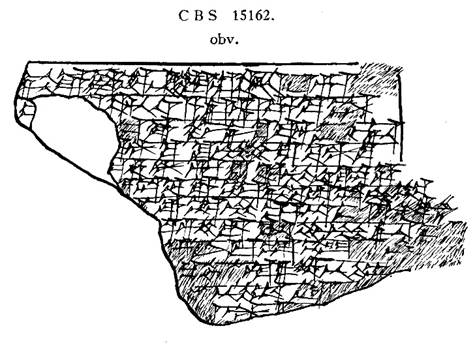

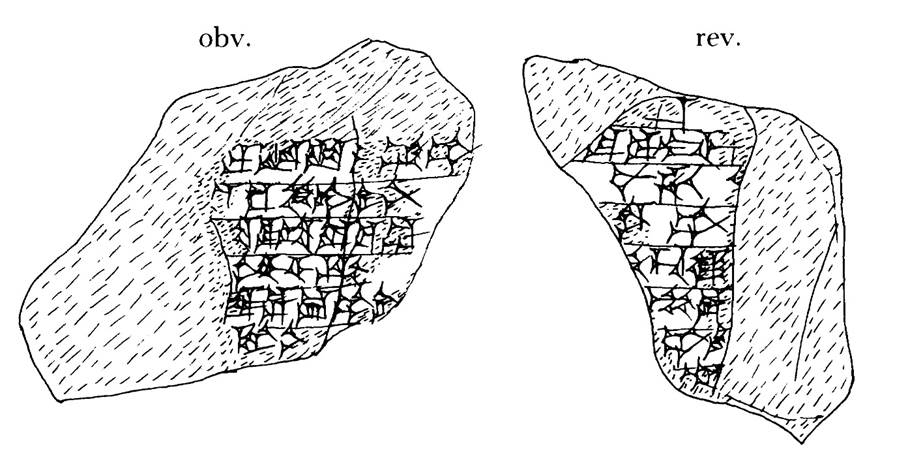

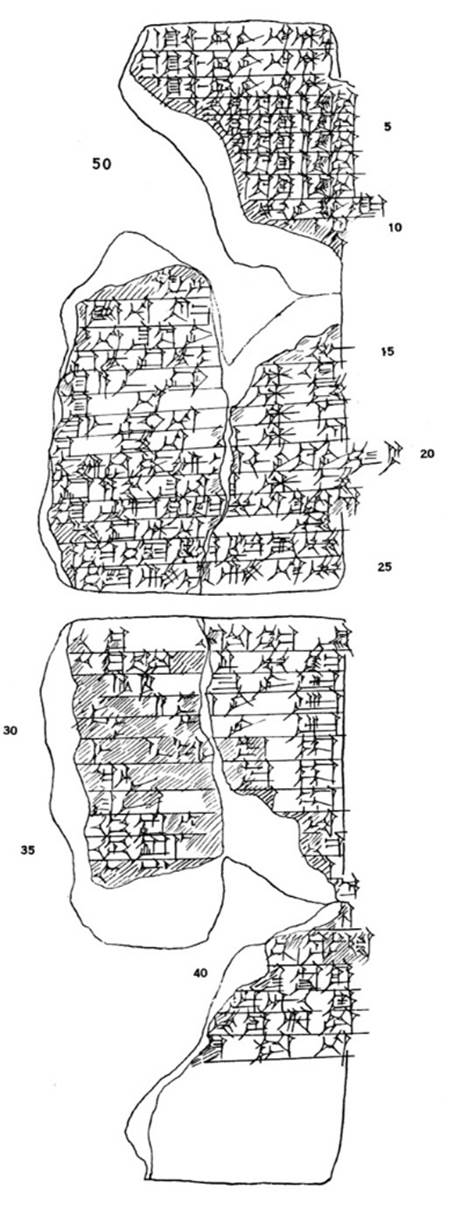

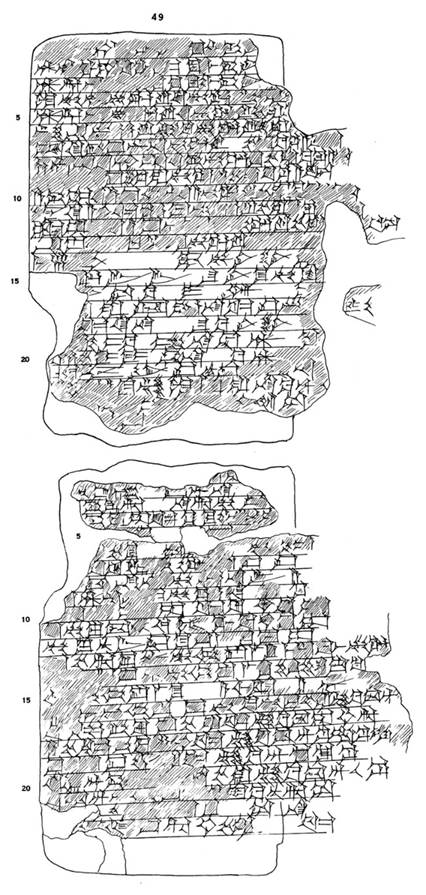

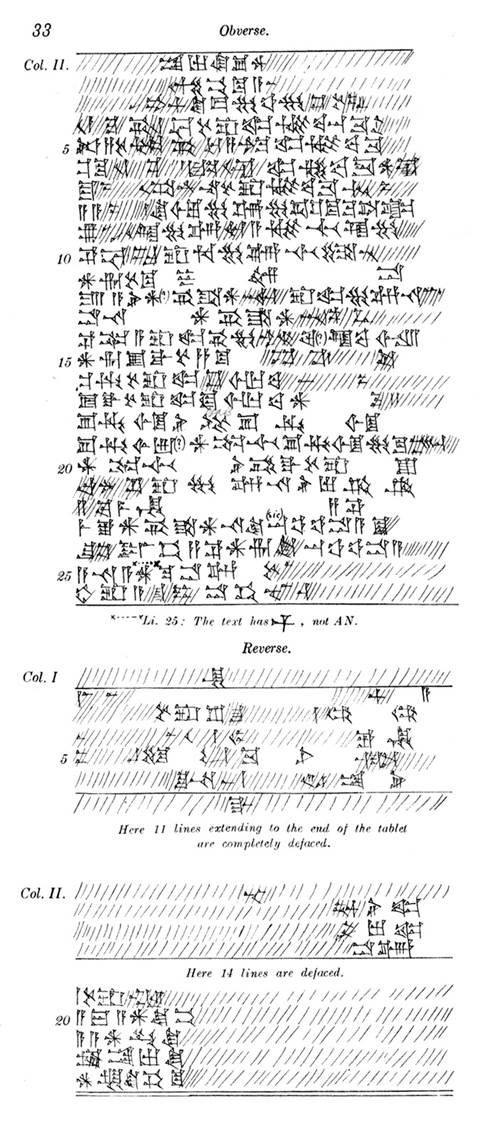

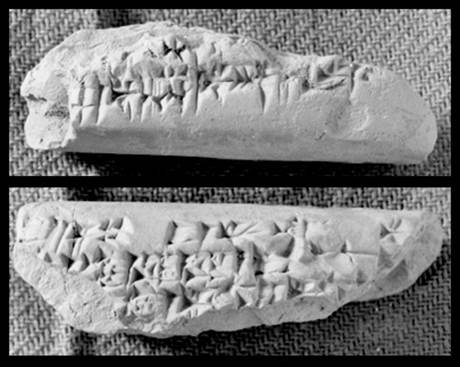

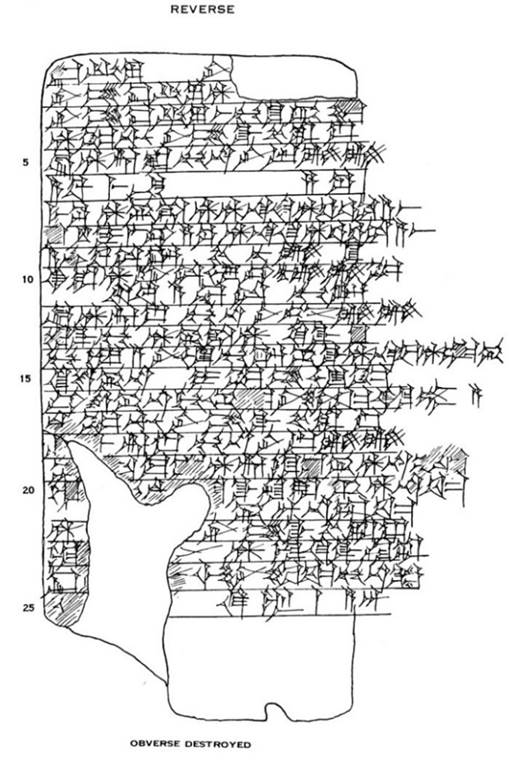

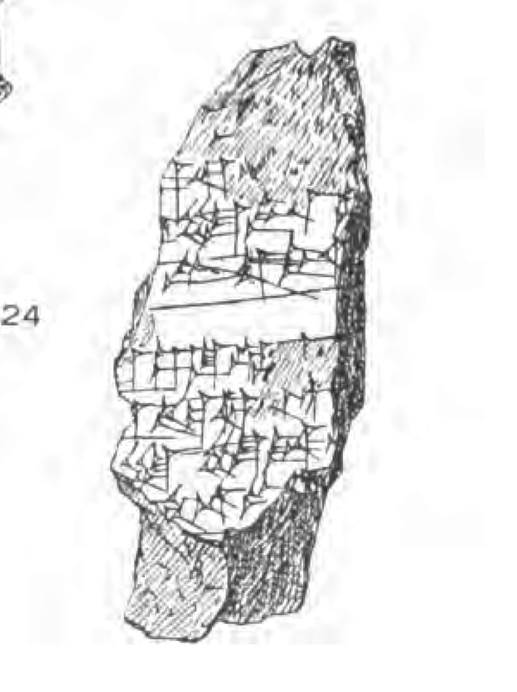

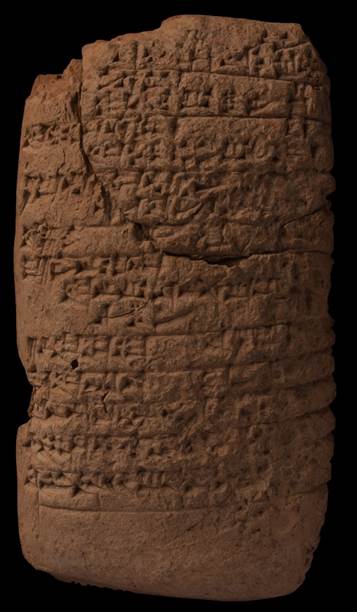

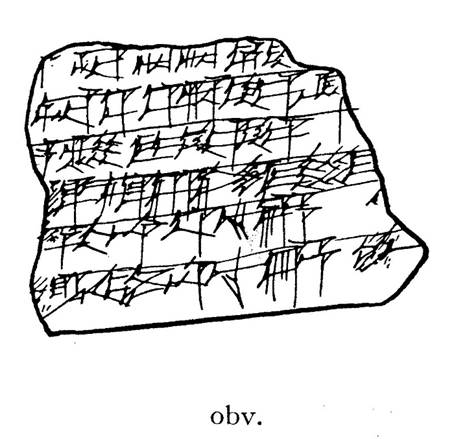

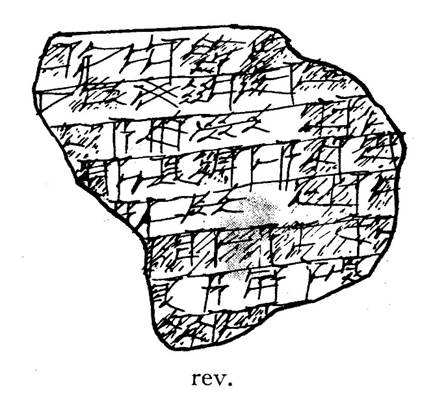

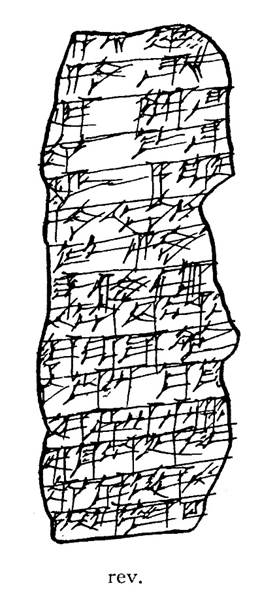

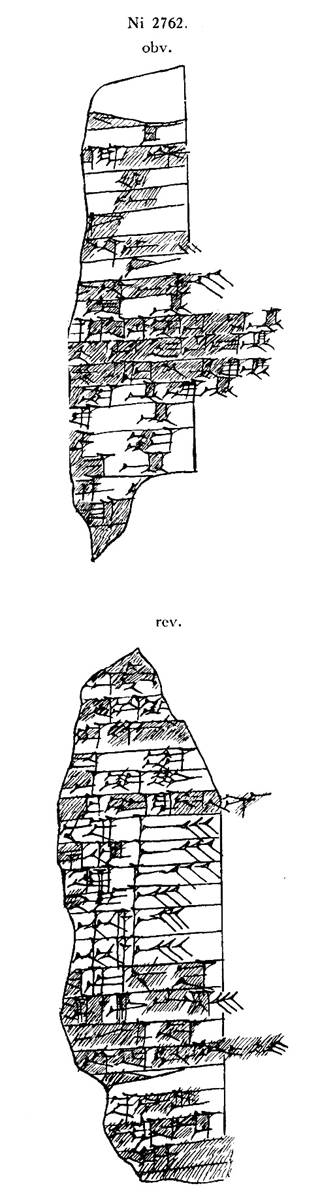

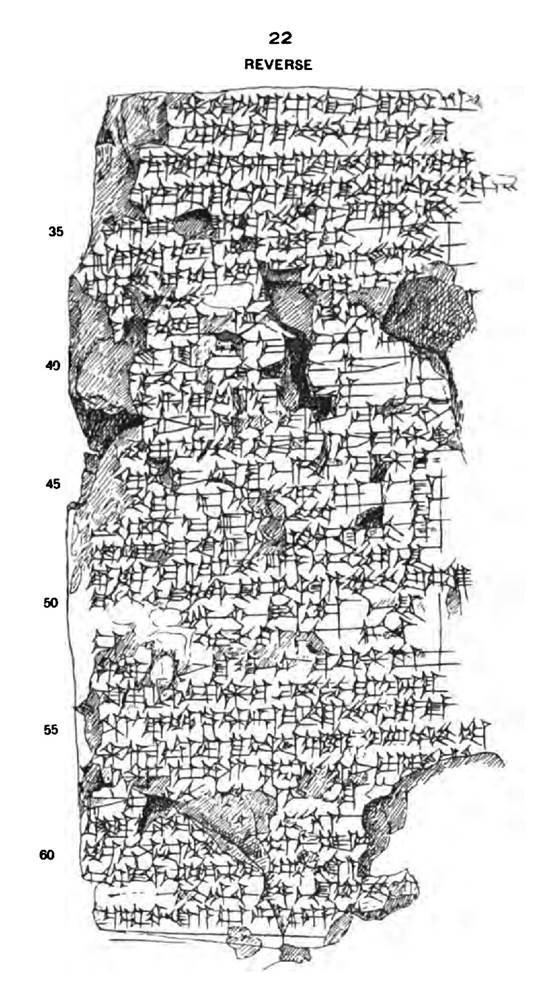

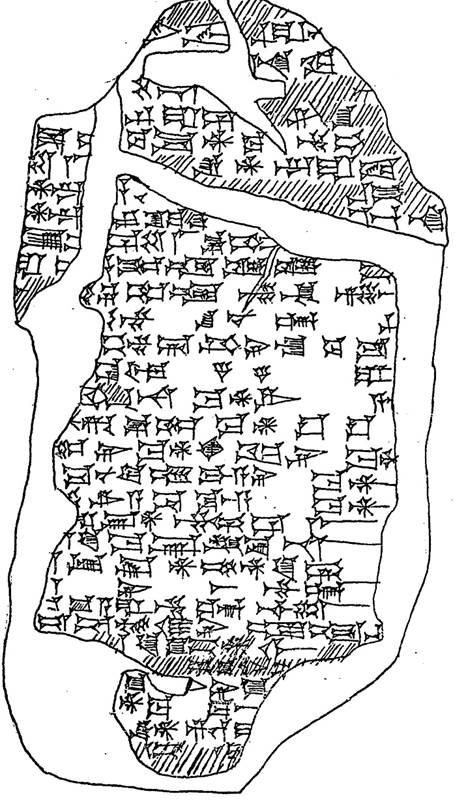

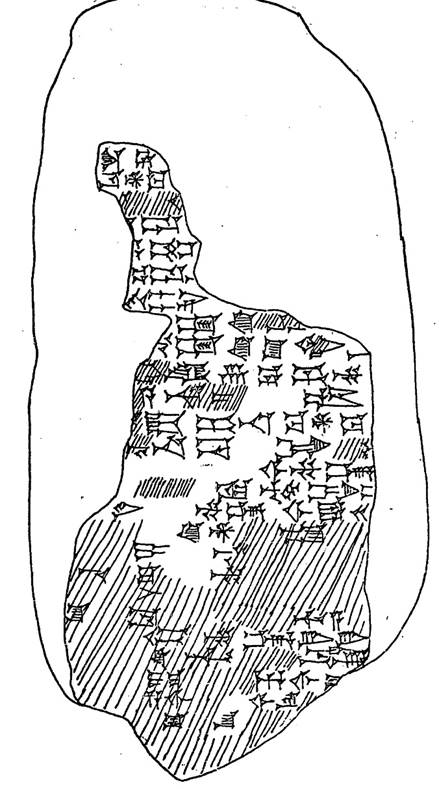

Figure 2.4. Sladek’s

published artifacts. Illustrations published by William R. Sladek, [Figure[s] I

– IX], “Inanna’s Descent to the Netherworld” (Ann Arbor: University Microfilms,

1974): 280-9. [While better photos of these artifacts exist, Sladek’s originals

are included to highlight the labor required in his efforts. The images have

been cropped and grouped together to save space, but are otherwise unmodified.]

The

remainder of the 1970s and 1980s featured further translations by Kramer and

Jacobsen, as well as new artifact publications by Bendt Alster (1946-2012),[95]

a Danish scholar. While Kramer actively published more translations leading up

to his passing in 1990, a most notable version of ID was included in a 1983

book he co-authored with Diane Wolkstein, a cultural folklorist.[96]

In Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer,

Kramer and Wolkstein provided a public-friendly and easy-to-read version of ID,

as well as a summary of scholarship in the entire field.[97]

This version, like Jacobsen’s a few years later, was written in verse

form, meaning that the lines were short and grouped in poetic stanzas.

Jacobsen also published his final version of ID in 1987 before passing away in

1993.[99]

It was thus the end of an era with the passing of Kramer, Sladek, and Jacobsen

before 1995.

Alster

spearheaded the resolution efforts of the ambiguous ending of ID by publishing

partial translations of ID in 1983[100]

and 1996[101]—effectively

filling in the remaining gap of lines 380-412 in the ETCSL version of ID. In

these final publications, Alster reinterpreted the ending of ID using artifact

UET 6/1 10[102]

and CBS 6894 by indicating that Inanna ultimately repented for giving her

husband up to the demons.[103]

It is worthy to note that Alster’s 1996 translation relied heavily (in some

cases solely) on CBS 6894, a fragment not listed as a cuneiform source

in the ETCSL version of ID.[104]

Ironically, this excluded fragment was the only artifact that contained usable

text for lines 380-412. In a final reversal, Alster concluded his translation

by arguing that the divine couple of Inanna and Dumuzi came to an agreement

whereby they would split time between the heavens and the netherworld—reversing

Sladek’s interpretation of Dumuzi not being a dying-and-rising god.[105]

With Alster’s contribution, the stage was set for the 1997 release of our

412-line (forty-eight artifact) translation of ID by the ETCSL.

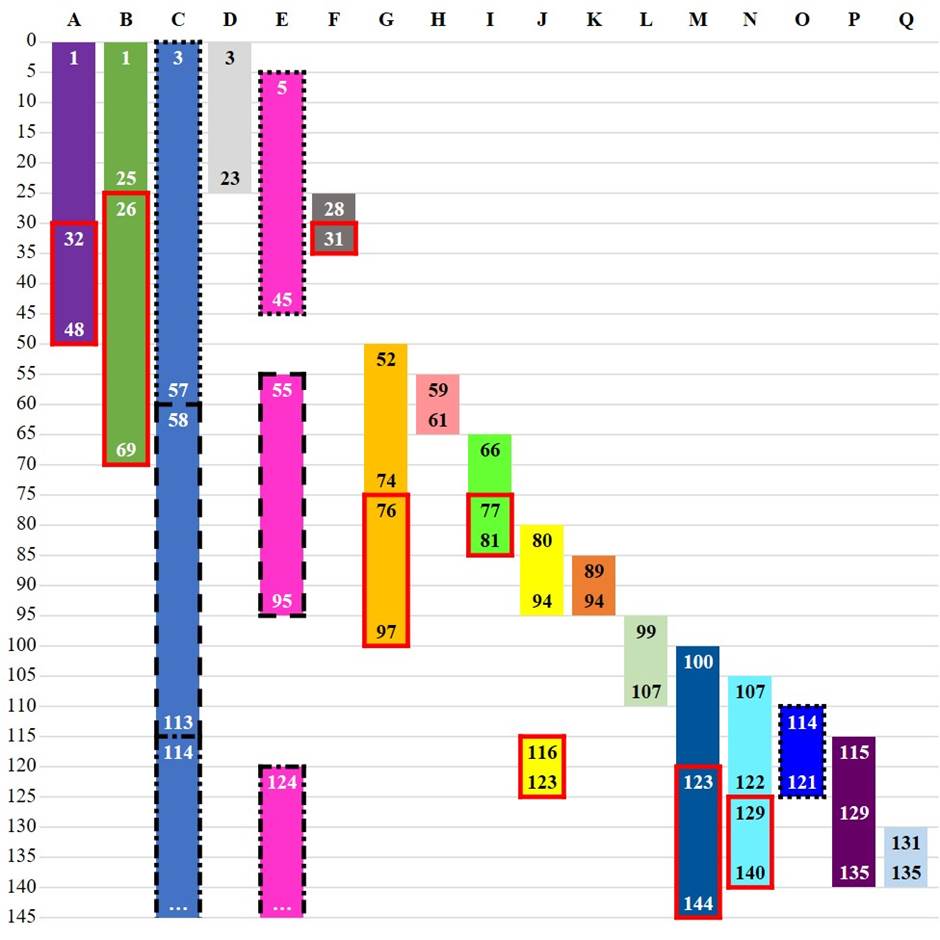

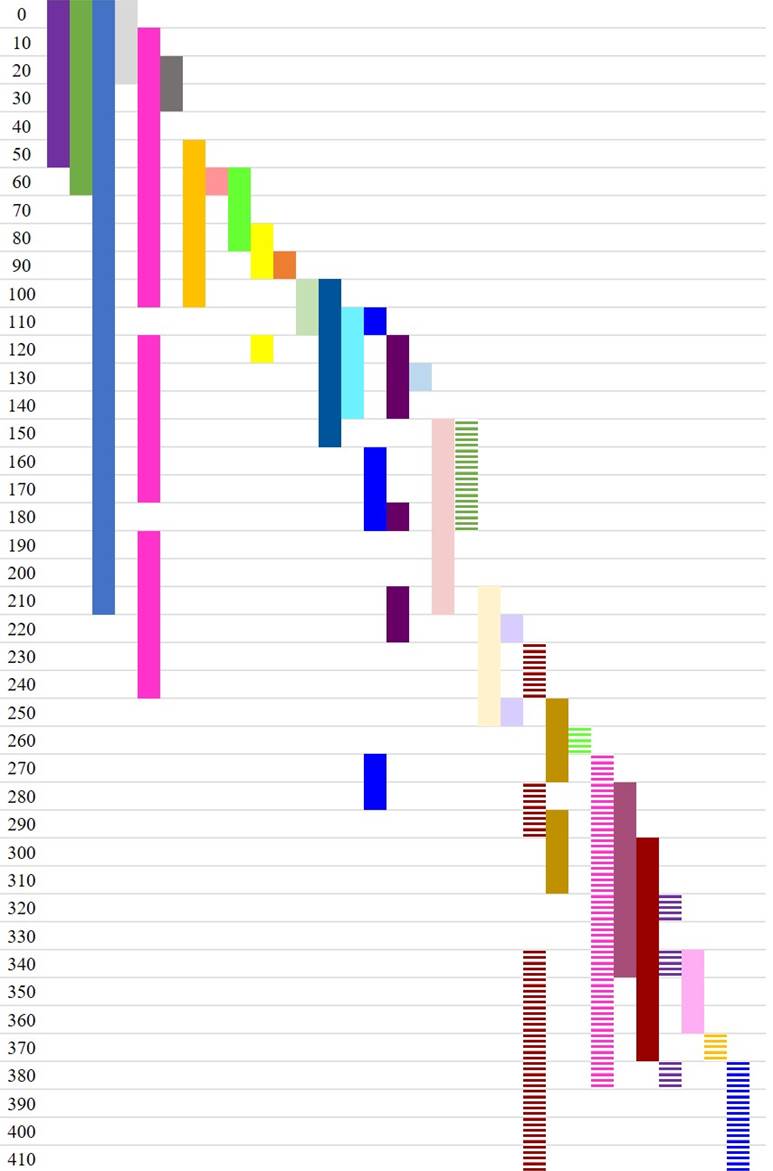

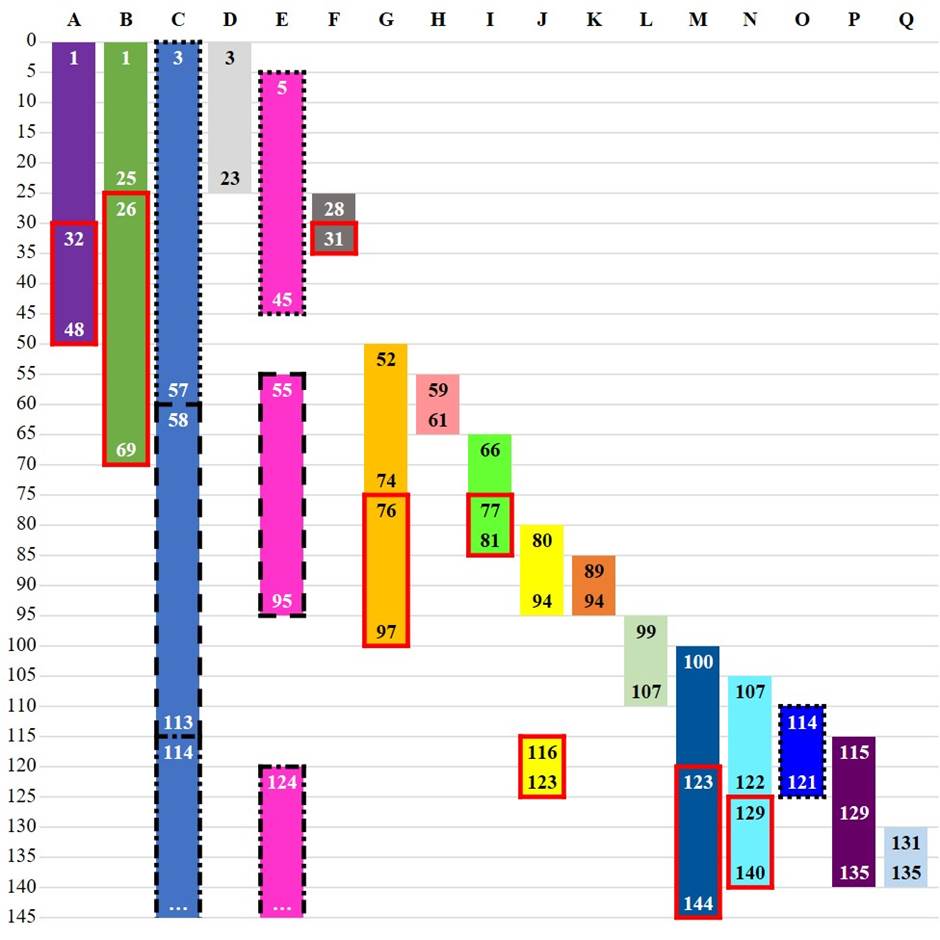

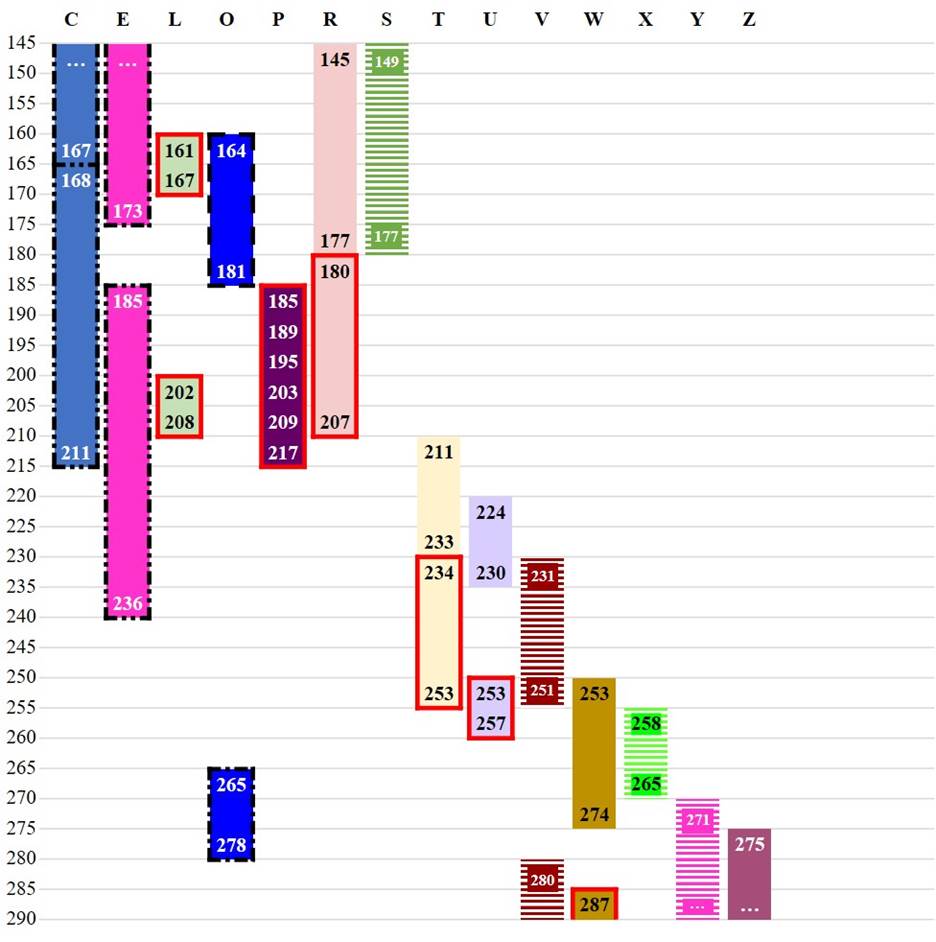

Having

chronologically reviewed the painstaking effort and coordination required over

the last one hundred years of scholarship, we can now—with full

appreciation—see the fruit of these labors in vivid color. As the table on the

following page shows, the decipherment of ID required stitching together the

textual contributions of many artifacts, thousands of miles apart. Each

fragment that was added helped improve the translation of existing passages or

provided fresh material for gaps, such as the last thirty lines. With the

initial 1997 publication of the ETCSL version of ID, a century of hard work and

collaboration came to fruition.

|

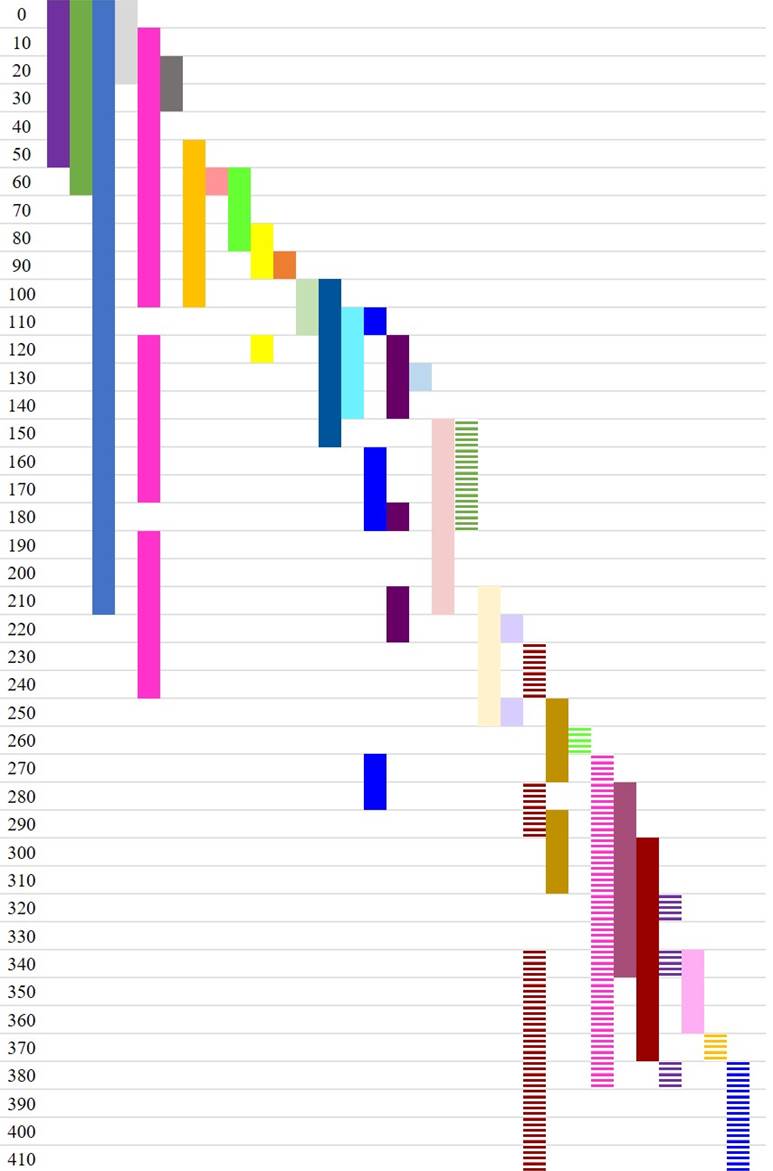

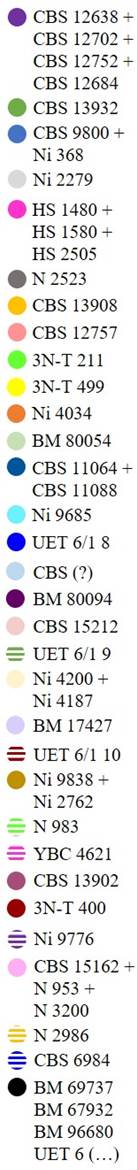

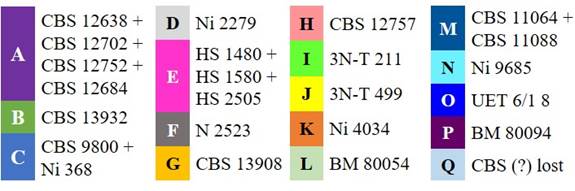

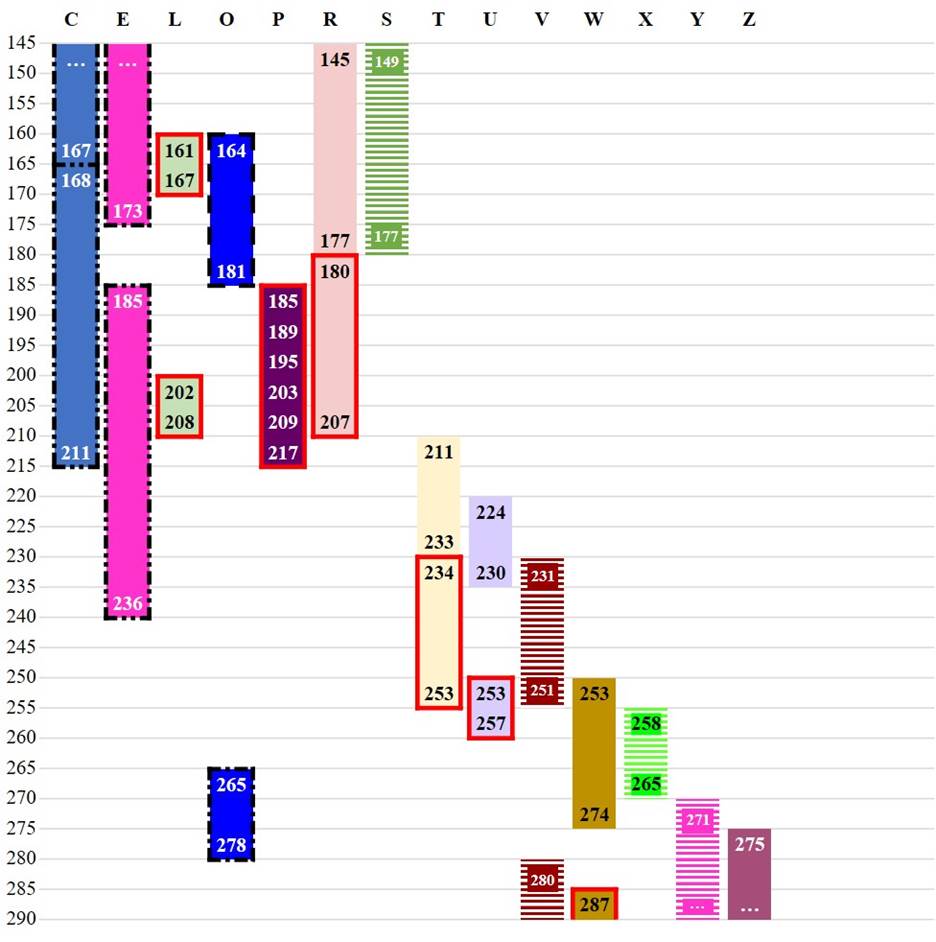

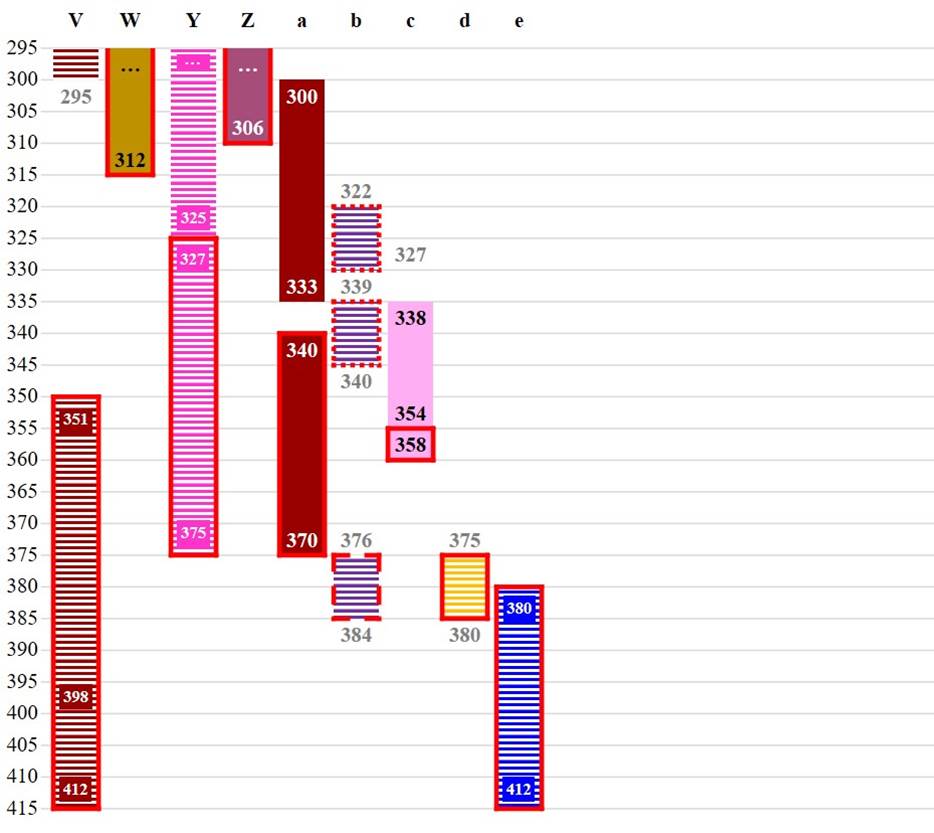

Table

1.1. Artifact waterfall view of “Inanna’s descent to the nether world,” ETCSL

(2001)

|

|

Line #

Cuneiform sources by line count and first appearance

|

Color

Key *

|

|

|

|

|

Note: See

exact line numbers, column numbers, tablet orientation, and more details in

Appendix B.

* BM 69737, BM 67932, BM 96680, and three UET 6 fragments did not seem to

provide text with line numbers.

|

The Digital Age (1997-2006)

The

internet enabled prestigious institutions like Penn, Oxford, and UCLA to expand

the availability of Sumerian literature to the entire world (for free, no

less). These institutions took advantage of digital publishing to offer free

cuneiform resources for a wider audience. Penn integrated the digital facet of

its offerings in 2004 with the launch of the Electronic Pennsylvania Sumerian

Dictionary (hereafter ePSD).[107]

The ePSD project was initially started in 1974 by Åke Sjöberg, the same person

who mentored Sladek during his influential dissertation publication.

The digital index offers translated texts as well as a robust online

dictionary. Unfortunately, however, the homepage indicates it has not been

updated since 2006, perhaps due to funding issues.[109]

In

1997, Oxford University began work on the Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian

Literature (ETCSL) under the guidance of Jeremy Allen Black (1951-2004),[110]

the main coordinator for the project. The project sought to publish a Sumerian

dictionary and literature index, but unfortunately lost its funding in 2006,

stagnating its progress.[111]

Despite this setback, the utility of ETCSL as a digital resource is still

important. In 2000, the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) launched

the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative (hereafter CDLI) as a means of

distributing scholarly research on cuneiform to a wider, non-local audience.[112]

Figure 2.5. Digital libraries with Sumerian

literature. Illustration composite by Boban

Dedović. [See Appendix B for URLs and reference numbers of digital

resources related to ID]

The CDLI hopes to

make available all 500,000 artifacts it estimates exist in the form of

cataloged records, translations, transliterations, high-resolution photos, line

art (sketches), and composition materials.[113]

Indeed, almost every artifact we reviewed in this survey is contained within

composition number Q000343, which includes all fifty related source materials

for ID, as well as new ones.[114]

Any scholar that is serious about ID will undoubtedly take advantage of the

ePSD, ETCSL, and the CDLI.

Current Scholarship (2007-2019)

The

loss of institutional funding for key online resources and passing of notable

experts like Black in 2004 and Alster in 2012 has, perhaps, left a gap in

current scholarship for ID. As of this writing, all of the big five

scholars originally mentioned have passed away. Also, most of the institutions

that shared their research seem to be troubled by a lack of funding for

Sumerian literature and cuneiform related projects. Additionally, the digital

age and its transformation of the publishing industry has seen many notable

journals go defunct. Mainly, most of the journals that the scholars of ID

published their findings in seem to be out of print or acquired by other

parties. In abstaining from pessimism, we can say there is good news regarding

the CDLI. As of May 17, 2019, CDLI’s About and Staff pages seem to be regularly

updated under the leadership of their principal investigator, Robert K.

Englund.[115]

The CDLI is actively publishing user-submitted journal articles, notes, and

extensive preprints of future volumes of work—all online and available for the

general public.[116]

Indeed, the most recently listed publications were dated April 16, 2019, and

attributed to Jeremiah Peterson at the CDLI.[117]

These publications are unpacking more UET series artifacts, first published in

the 1960s, with more commentary and revised translations.

By

looking at the most recent composite version of ID on the CDLI’s website, we

can, perhaps, peer into what progress is being made. In reviewing composite

number Q000343 (the CDLI’s translation of ID), the score page lists a total of

seventy-eight artifact fragments.

Many of these fragments seem to be part of the UET (Ur Excavation Texts)

collection of artifacts, housed in the British Museum, and published by Aaron

Shaffer in his 2006 catalog of the same name.

These artifacts were probably documented or seen by Gadd and Kramer in 1963-6

and seem to provide robust textual contributions toward ID.

The translation of some of these UET artifacts is being done by the CDLI, as

previously cited by Jeremiah Peterson’s preprint record. Passage translation

improvements are being released, albeit in small parts. Some artifacts, like

the 3N-T ones from Sladek’s dissertation, have been re-cataloged under the IM

prefix (The IM prefix is the museum record number from the National Museum of

Iraq) . The remaining three artifacts listed on CDLI’s artifact source section

list MS 3281 and MS 3282 as forthcoming publications by Konrad Volk, a German

Assyriologist.

It is, therefore, likely that we can expect continued artifact translation

publications and translation revisions to ID—hopefully, with the promise of a

more robust and agreed-upon ending.

Other

prominent scholars, as well as institutions, are actively contributing to

better understanding ID. Since 1995, Dina Katz has published various journal

articles and books that try to reconstruct Inanna’s place in the pantheon of

Sumerian literature and deities.[122]

Other universities, like Cornell, are actively building their own digital

libraries that resemble the ETCSL and CDLI (Cornell’s efforts are in

collaboration with the CDLI).[123]

The University of Leiden in the Netherlands seems to be providing a population

of interested scholars who are willing to migrate to the United States to join

such research efforts. Numerous independent scholars are also doing graduate

work on the matter. A recent search for scholarship related to ID on academia.edu

yielded hundreds of search results within the last year.[124]

As Kramer did so in 1937, German scholars like Nikita

Artemov are also challenging previous scholars’ interpretations of ID. For

example, in 2012, Artemov contributed to a print volume whereby he asserted

that the Sumerian concept of the netherworld represented geography indicative

of the material Earth; that is, he argued that the netherworld represented a

real location on a map, not an underground or metaphorical one.

Sladek and others have maintained that the netherworld was an underground

location. There are surely other ID scholars positing ideas that challenge the

work of previous ones, and the present survey, unfortunately, cannot address

them all. Ultimately, while the major individuals that led initial scholarship

on ID have passed, their work seems to be continuing in the form of fresh

ideas, new individuals, and online tools accessible to a broader audience and

readership.

The Future of ID (2020 and Beyond)

Having

covered the broad strokes of past scholarship on ID, let us briefly consider

what the future may hold. While I wish I could present the reader with clear

visibility into the future research direction of this fascinating myth, I do

not have 20/20 vision. Puns aside, many disciplines require that authors reserve

a section at the conclusion of the article for research limitations and

promising areas of future inquiry. In affirming my limited experience in

cuneiform script and Sumerian translation, I can only offer a brief list of

areas that seem to be promising for future scholars who are properly trained. I

must disclose to the reader that the items mentioned hereafter are entirely

speculative and pure conjecture—that is, research efforts in these areas may

not yield meaningful progress for ID or our understanding of Sumer.

Additionally, previous works unknown to me or simultaneously published

scholarship may have covered these areas already. Finally, I would like to make

it crystal clear that in sharing my perspective on promising areas of research,

I harbor no intention or attitude of disrespect toward the many scholars who

contributed to the contents of the present survey. These scholars are indeed

giants, and worthy of a familiar phrase by Isaac Newton; if I am, by incredibly

good fortune, seeing anything interesting, it is because I am standing on their

shoulders.

In

carefully reviewing and documenting fifty ID artifacts and some fifty

translations, there are three outstanding pink elephants. For instance,

a savvy historian will likely immediately recognize the problem associated with

grouping fifty artifacts with extremely dubious (or nonexistent) provenance

documentation into the same time period. Indeed, the CDLI, British Museum, Yale

Museum, and Penn Museum all date the artifacts as belonging to the Old

Babylonian period (ca. 1900 - 1600 BCE). The general cultural period seems to

have been adopted from the earliest publications by Langdon. This dating

estimate was factually mentioned in most publications as a single sentence and

never challenged, to my knowledge. There does not seem to be any scholarship or

analysis related to dating methodology or difference of opinion whatever. Thus,

it seems promising to take advantage of newer and more robust dating methods in

order to reassess the core assumption of the cultural period.

The

second matter that may deserve future scholarship is the curious discrepancy

between depictions and associations between Inanna and Ishtar. Objectively

speaking, ID is a more recently discovered piece of Sumerian literature and was

differentiated from the Assyrian “The Descent of Ishtar” (hereafter AI) in the

last 120 years, according to previous references by Sladek. Indeed, scholarship

related to the chronologically latter composition seems to be overlapping

extensively with the former. The present survey intentionally withheld from

mentioning AI more extensively because of the significant objective differences

between the two compositions. For example, ID consists of 412 lines while AI is

roughly a fourth of the line count. Several previous scholars have agreed that

Sumerian Inanna was contextually different. In commenting that Inanna seemed

more subdued than her Assyrian counterpart, Kramer’s folklorist, Diane

Wolkstein, likely did not nearly go far enough.[126]

Inanna and Ishtar are often referenced as one and the same (sometimes a single

deity named Inanna/Ishtar) when perhaps they should not be. It may

therefore be beneficial to more carefully review the contextual differences in

mentality, linguistic differences, cultural diffusion, and context that one

thousand years of oral transmission can bring to a piece of mythology.

The

third matter that may deserve future attention is the question of modality and

audience analysis. It is reasonable to presume that the scholars who prepared

the numerous translations sat and read the composition of ID many times over.

While careful readings of source materials are important, interesting questions

related to content consumption arise. If ID was meant to be read, who could

have read it between 2,500 BCE and 1,800 BCE? Indeed, literacy rates present an

immediate modality problem. As a starting point, global literacy rates in 1820

CE were estimated to be only 12 percent.[127]

The lone strongly accepted study of literacy rates in ancient times was seemingly

done by William Harris in 1989. Harris found that in Roman times (ca. 100 BCE),

the literacy rate was roughly between 5 and 10 percent, for males in

certain provinces.[128]

If we backtrack even further to ca. 2000 BCE—just roughly one thousand years

after the cuneiform writing system was likely invented—we can broadly speculate

that there was no mass literacy or readership.[129]

The modality then could not have been formal readership as we practice today.

Indeed, Kramer and many others have indicated that stories like ID were poetry

intended for public consumption with the aid of a musical instrument.[130]

However, this modality consideration is often tucked away in a footnote when perhaps

it should not be. Perhaps this information deserves more concrete and

scientific study in all facets of interpretation and analysis.

In

light of the aforementioned literacy considerations, interesting questions

emerge—who was ID initially written for, why was it written, and what are the

implications of the answers to these questions? Was ID consumed by the masses

in a public gathering at major cities like Ur and others, or was it intended

for private royal gatherings of kings and Sumerian aristocracy? Did someone

directly authorize its initial composition or was it an oral story that

everyone just knew? What purpose (if any at all) did ID have in the broader

scheme of Sumerian culture, especially during the turbulent times of the third

and fourth Ur dynasties? The questions presented depart massively from

spiritual or existential inquiry and dig deeper into the practical, political,

and social facets of the poem’s role. More can be said about this matter, but

that endeavor is for future scholars with proper training to unpack.

Conclusion

In

these last few pages, we have outlined potential areas of research for ID. Of

main concern was the issue of unknown artifact provenance, particularly as it

relates to dating methods. The contextual differences between the Sumerian

Inanna and Assyrian Ishtar were also cited as promising for the future of

clarifying how the myth either evolved or was diffused into the latter from the

former. Finally, statistics on literacy rates in ancient times were highlighted

to show how the poetic nature of ID may provide important clues as to how it

was meant to be consumed. Given the general trajectory of digital publishing

and the desire for inclusive access of resources, it is highly likely that new

and innovative digital indexes and tools will be designed for broader

audiences. Such tools will likely connect researchers directly to the artifacts

and original scholarship without the need for many years of proprietary

training. The world is collectively

grateful for the digital efforts by institutions like Oxford, Chicago, Penn,

and UCLA, and more are likely to follow.

Whatever

future scholarship on ID yields, it is my sincere hope that the few pages I

have provided here will inspire and enable further interest in ID from all walks

of life—regardless of discipline or other factors. If anything (at all) can be

learned from the centennial survey presented, it is that advancements in

understanding ID will require a team effort whereby new individuals will build

on the work of prior generations. Perhaps then, we may hope to find out what really

happened to Inanna’s husband Dumuzi, why she would take a risky journey to be

killed and hung like a rotting piece of meat at the hands of her sister, and

whether she really repented for her actions. Then, finally, we may be

able to confidently peer not just at but into those fierce

alabaster carved eyes and see, as the Sumerians perhaps saw, a glimpse of

Inanna’s divine catharsis—or nothing whatever.

Appendix A: Artifacts Table and Visualizations

When

attempting to search for artifact publications related to ID, navigating

through obscure abbreviations for defunct journals may cause researchers to

spend more time than is necessary. Table 3.1 provides an organized

manifest of all artifacts related to ETCSL’s 2001 version of ID and an

abbreviation of each publication. Such a table may save future researchers

valuable time and energy. In a similar vein, Table 3.2 provides a

comprehensive version of Table 1.1, whereby every artifact utilized in the

ETCSL version of ID is listed by order of translated line number, first

appearance, and frequency in a waterfall style view. All 412 lines of ID are

mapped on axis A with respect to the associated artifact on axis B. A color key

provides a museum number reference guide for the three-page table. Some

artifacts have been purposefully excluded from this table and those reasons are

provided in the footer of the table.

|

Table

2.1. Detail artifact table for “Inanna’s descent to the nether world,” ETCSL (2001)

|

|

|

#

|

Museum number(s)

and corresponding lines of ID

|

Publications

*

|

|

|

1/A

|

CBS

12638 + 12702 + 12752 + 12684 (4 artifacts)

Lines: 1-31

(obverse), 32-48 (reverse)

|

SEM/OIP 15,

Chiera, 1934, pl. 50.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pg. 303.

JCS 5, Kramer, 1951.

|

|

|

2/B

|

CBS

13932

Lines: 1-25

(obverse), 26-29 (reverse)

|

SEM/OIP 15,

Chiera, 1934, pl. 49.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pg. 303.

JCS 5, Kramer,

1951.

|

|

|

3/C

|

CBS

9800 + Ni 368

Lines: 3-57

(Column I), 58-84, 89-113 (Column II), 114-167 (Column III), 168-211 (Column

IV)

|

BE, Langdon,

1914, pl. 33.

SRT, Chiera,

1924, pl. 53.

RA 34, Kramer,

1937.

RA 36, Kramer,

1939.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pg. 293.

JCS 5, Kramer,

1951, pg. 1.

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 100.

|

|

|

4/D

|

Ni

2279

Lines: 3-23

(obverse), destroyed (reverse)

|

BE 31, Langdon,

1914, pl. 34.

JAOS, Kramer,

1940, pg. 246.

|

|

|

5/E

|

HS

1480 + HS 1580 + 2505

Lines: 5-45

(Column I), 55-95 (Column II), 124-173 (Column III), 185-236 (Column IV)

|

TMH NF 3, Kramer

& Bernhardt, 1961, pl. 2.

PAPS 107,

Kramer, 1963, pg. 256-7, figure III.

|

|

|

6/F

|

N

2523

Lines: 28

(obverse), 29-31 (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 281, Figure I.

|

|

|

7/G

|

CBS

13908

Lines: 52-74

(obverse), 76-97 (reverse)

|

SEM/OIP 15,

Chiera, 1934, pl. 48.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pg. 303, pl. 5.

JCS 5, Kramer, 1951,

001.

|

|

|

8/H

|

CBS

12757

Lines: 59-61

(obverse), destroyed (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 282, Figure II.

|

|

|

9/I

|

3N-T

211 (IM 058380)

Lines: 66-76 (obverse), 77-81 (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 283, Figure III.

|

|

|

10/J

|

3N-T

499 (IM 058522)

Lines: 80-94 (obverse),

116-123 (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 284, Figure IV.

|

|

|

11/K

|

Ni

4034

Lines: 89-94

(obverse), destroyed (reverse)

|

SLTNi, Kramer,

1944, pl. 030.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pl. 10, pg. 323.

|

|

|

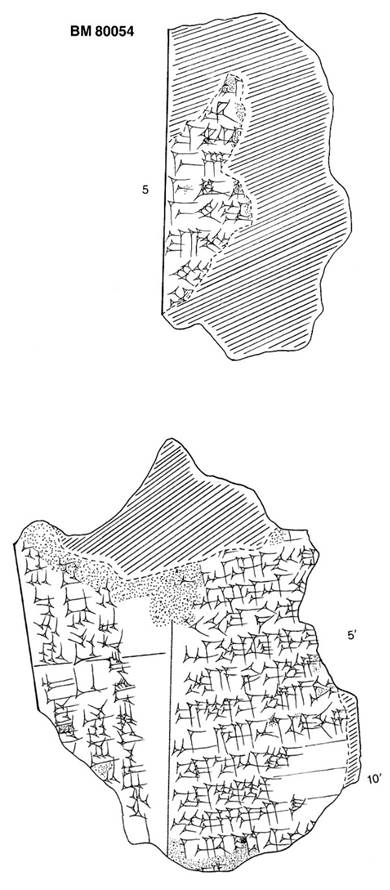

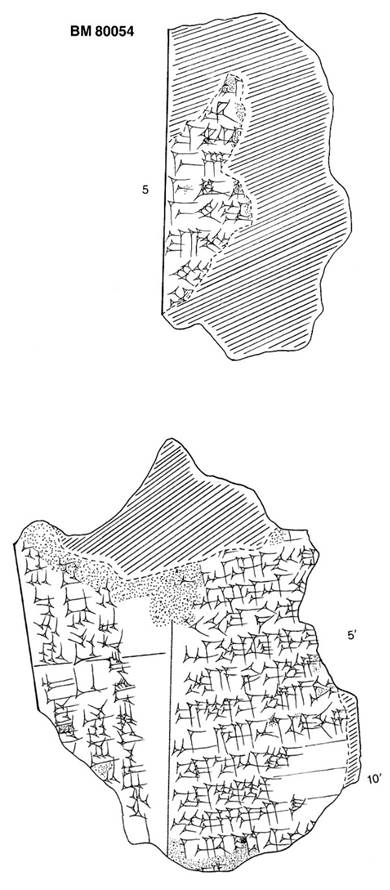

12/L

|

BM

80054

Lines: 99-107

(obverse), 161-7 and 202-8 (reverse)

|

CT 58, Alster,

1990, pl. 49a.

|

|

|

13/M

|

CBS

11064 + 11088

Lines: 100-23

(obverse), 124-44 (reverse)

|

PBS 5, Poebel,

1914, pl. 023.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pg. 303.

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 101.

|

|

|

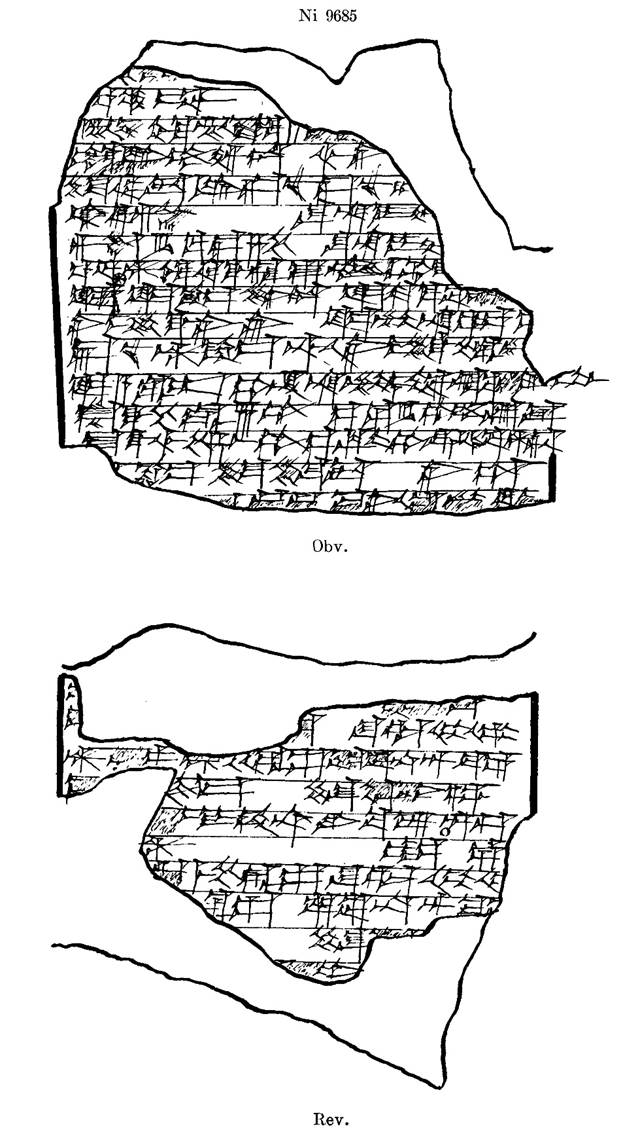

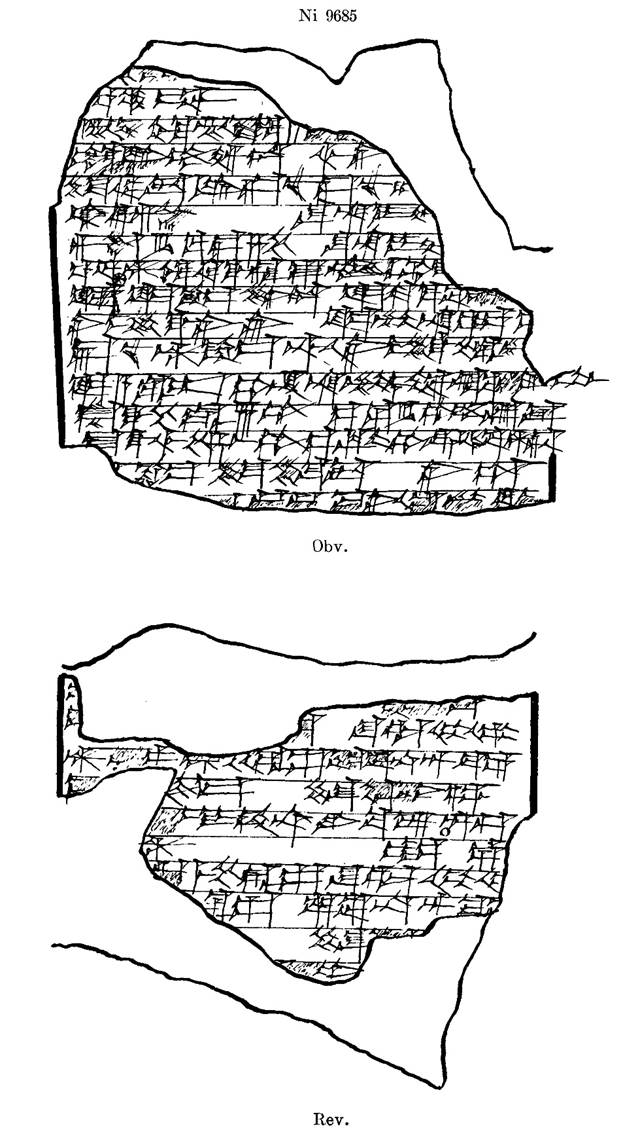

14/N

|

Ni

9685

Lines: 107-22

(obverse), 129-40 (reverse)

|

JCS 4, Kramer,

1950, p. 214.

Sladek, 1974,

pg.101.

|

|

|

15/O

|

UET

6/1 8 (UET VI 8)

Lines: 114-121

(Column I), 164-181 (Column II), 265-278 (Column III)

|

UET 6 8, Kramer

& Gadd 1963.

UET 6 8, Kramer

& Gadd 1966.

UET 6 8,

Shaffer, 2006.

|

|

|

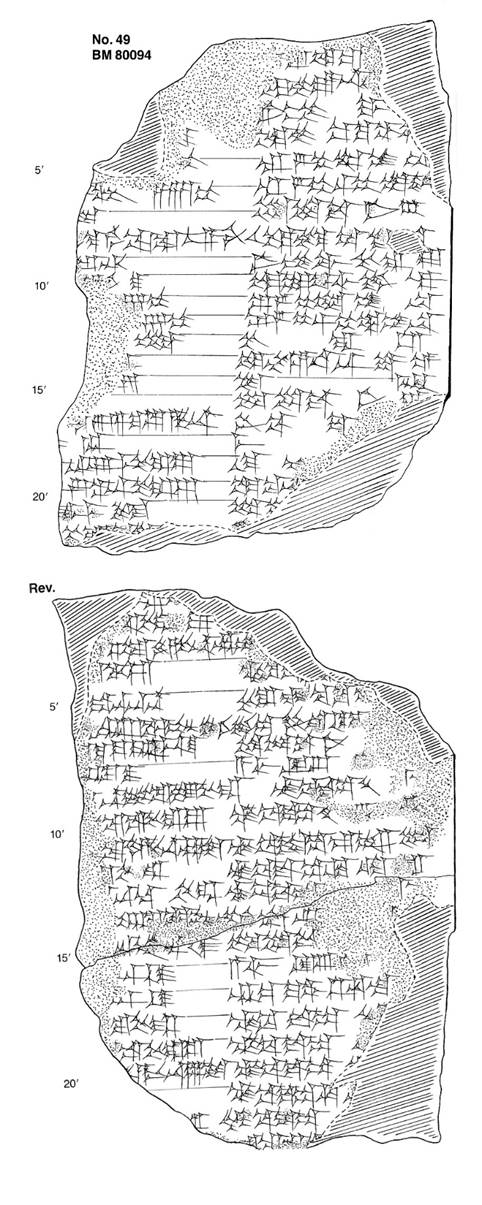

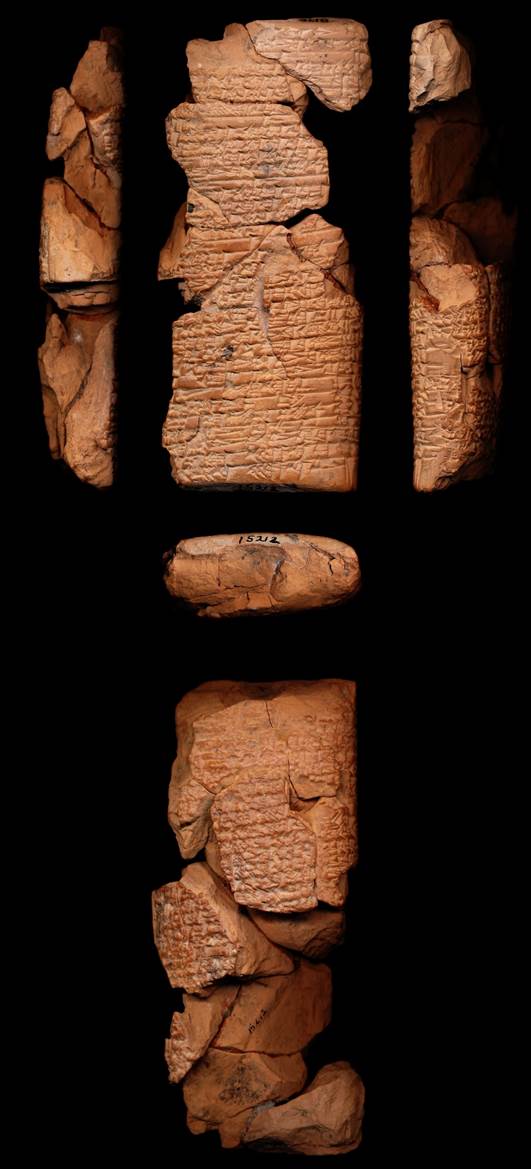

16/P

|

BM

80094

Lines: 115-129,

130-135 (obverse), 185-189, 195-203, 209-217 (reverse)

|

CT 58, Alster,

1990, pl. 49b.

|

|

|

17/Q

|

CBS

(?) lost artifact

Lines: 131-135

(obverse), destroyed (reverse)

|

PBS 5 24,

Poebel, 1914, pl. 24.

|

|

|

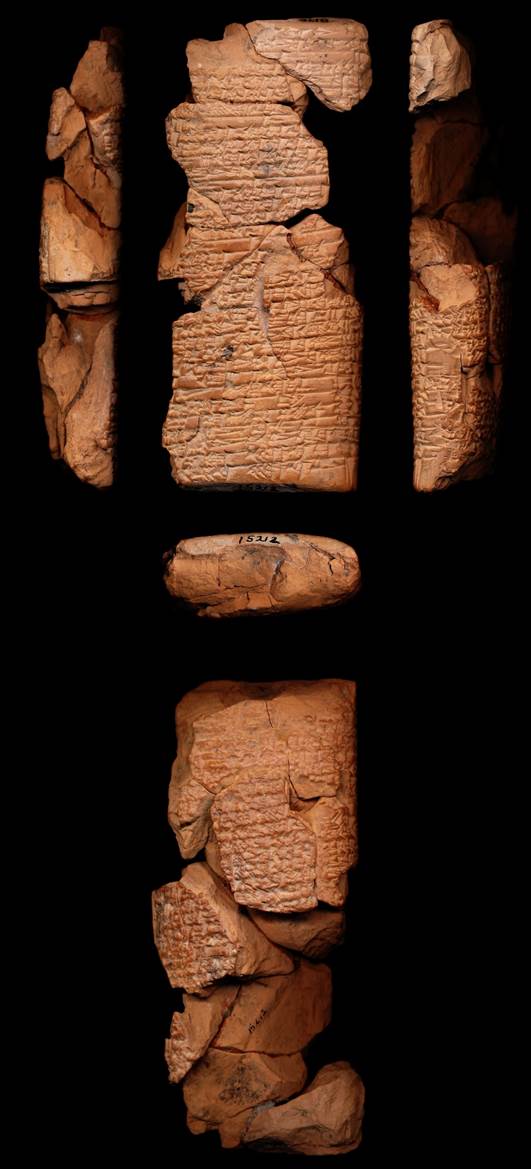

18/R

|

CBS

15212

Lines: 145, 147-149,

150-177 (obverse), 180-207 (reverse)

|

BASOR 79,

Kramer, 1940, pg. 22-3.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pl. 7.

|

|

|

19/S

|

UET

6/1 9 (UET VI 9)

Lines: 149,

151-154, 156-166 (obverse), 167-177 (reverse)

|

UET 6 9, Kramer

& Gadd 1963.

UET 6 9, Kramer

& Gadd 1966.

UET 6 9,

Shaffer, 2006.

|

|

|

20/T

|

Ni

4200 + Ni 4187

Lines: 211-233

(obverse), 234-253 (reverse)

|

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pl. 8.

PAPS 107,

Kramer, 1963, pg. 525.

SLTNi, Kramer,

1944, pl. 028.

RA 36, Kramer,

1939, pg. 78.

|

|

|

21/U

|

BM

17427

Lines: 224-230

(obverse), 253-257 (reverse)

|

CT 42, Figulla,

1959, pl. 03.

JCS 23, Kramer,

1970, pl. 010.

|

|

|

22/V

|

UET

6/1 10 (UET VI 10)

Lines: 231-251,

280-295 (obverse), 351-398 (reverse), 398-412 (reverse)

|

UET 6 10, Kramer

& Gadd 1963.

UET 6 10, Kramer

& Gadd 1966.

UET 6 10,

Shaffer, 2006.

|

|

|

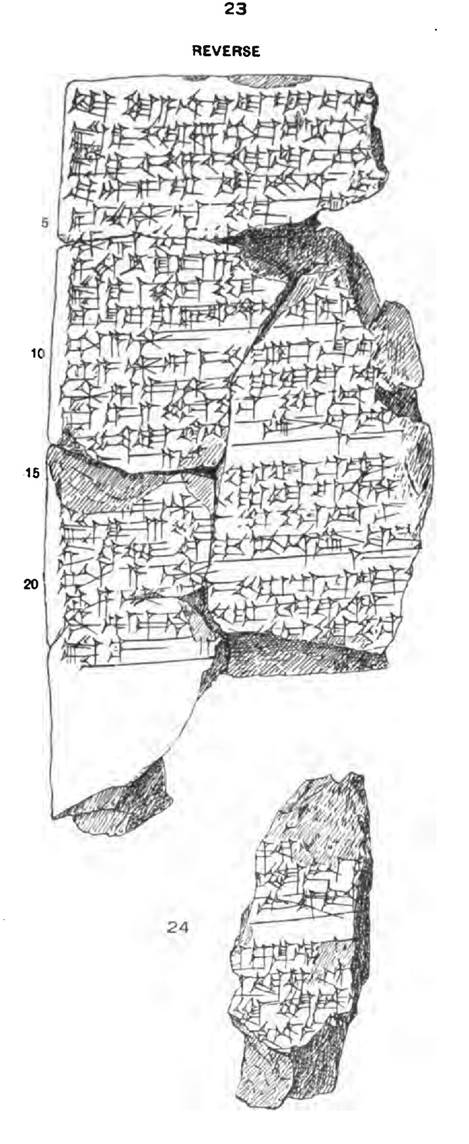

23/W

|

Ni

9838 + Ni 2762

Lines: 253-274

(obverse), 287-312 (reverse)

|

ISET 2, Kramer,

1976, pl. 17, Ni 9838.

SLTNi, Kramer,

1944, pl. 029.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pl. 8, Ni 2762.

PAPS 107,

Kramer, 1963, pg. 524, fg. 8, Ni 9838.

|

|

|

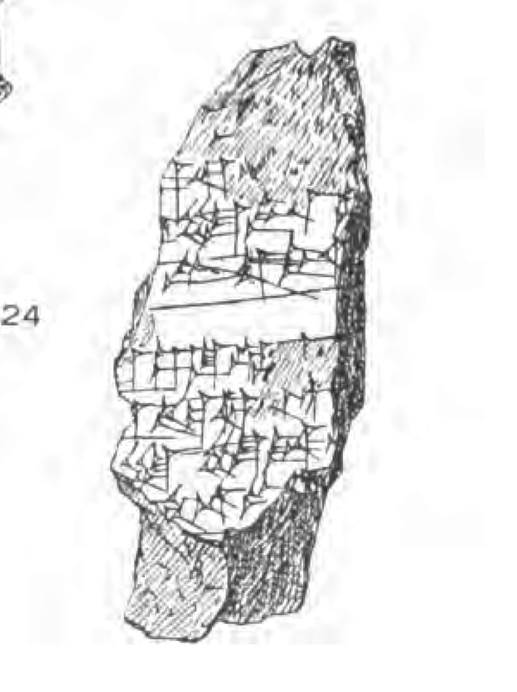

24/X

|

N

983

Lines: 258-265

(obverse), destroyed (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1975,

pg. 285, Figure V.

|

|

|

25/Y

|

YBC

4621 (now YPM BC 018686)

Lines: 273-325

(obverse), 327-375 (reverse)

|

JCS 4, Kramer,

1950, pg. 212-3.

ASJ 18, Alster,

1996.

|

|

|

26/Z

|

CBS

13902

Lines: 275-306

(obverse), 307-339 (reverse)

|

PBS 5, Poebel,

1914, pl. 022.

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pl. 9.

JCS 5, Kramer,

1951.

|

|

|

27/a

|

3N-T

400 (Museum No. IM 058460)

Lines: 300-333

(obverse), 340-370 (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 286-7, Figures VI-VII

|

|

|

28/b

|

Ni

9776

Lines: Destroyed

(obverse), 322-327, 339-340 (Column I, reverse), 376-384 (Column II, reverse)

|

ISET 1, Kramer

& Muazzez, pg. 183, pl. 025.

|

|

|

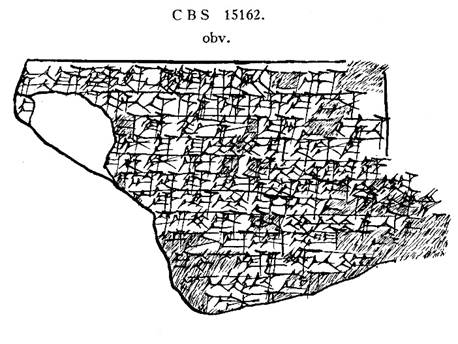

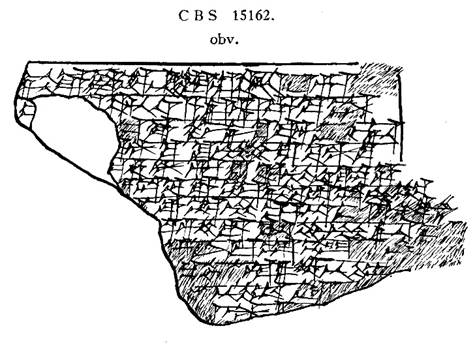

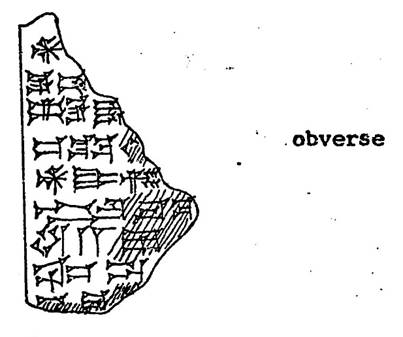

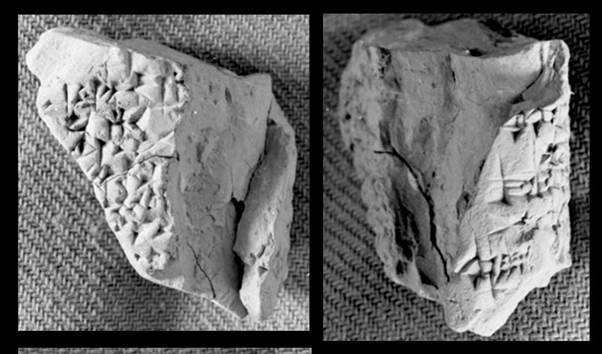

29/c

|

CBS

15162 + N 953 + N 3200

Lines: 338-354

(obverse), 358 (reverse), 345-351 (obverse)

|

PAPS 85, Kramer,

1942, pl. 10, CBS 15162.

Sladek, 1974,

pg. 288, Figure VIII.

BPOA 09 033,

Peterson, 2011.

|

|

|

30/d

|

N

2986

Lines: Different

composition (obverse), 375-380 (reverse)

|

Sladek, 1974,

Figure IX

JCS 29, Sjöberg,

1977, pg. 33.

|

|

|

31/e

|

CBS

6894

Lines: Destroyed

(obverse), 380-412 (reverse)

|

ASJ 18, Alster,

1996, pg. 10.

|

|

|

32/f

|

BM

67932

Lines: (?)

|

BMDR, 67932.

|

|

|

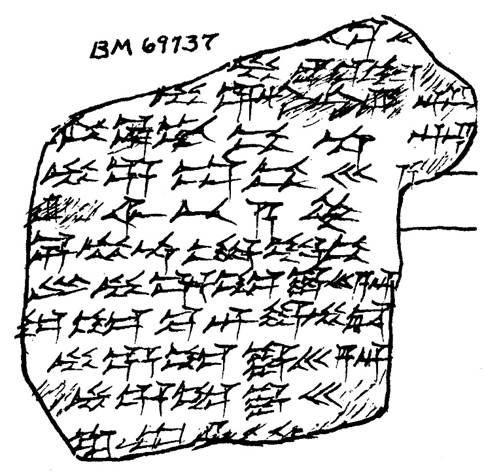

33/g

|

BM

69737

Lines: (?)

|

PAPS 124,

Kramer, pg. 297-8, 302.

CT 58, Alster

& Geller, 1990, pl. 50, pg. 62.

|

|

|

34/h

|

BM

96680

Lines: (?)

|

PAPS 124,

Kramer, 1980, pg. 297-8.

BA 46, Kramer,

1983, pg. 74.

BMDR, 96680.

AuOr

05, Kramer, 1987, 89-90.

|

|

|

35/i

|

UET

6 *269

|

CDLI

|

|

|

36/j

|

UET

6 *306

|

CDLI

|

|

|

37/k

|

UET

6 *320

|

CDLI

|

|

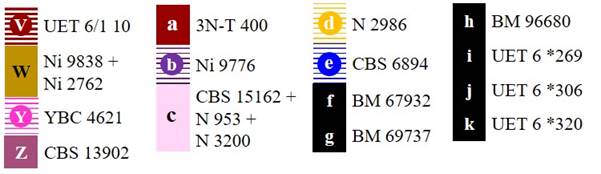

Table

2.2. Waterfall view of cuneiform sources for “Inanna’s Descent” (lines 1-145)

|

|

Cuneiform

sources by line count and first appearance

|

|

Artifact color

key

|

Border key

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table

2.2. Waterfall view of cuneiform sources for “Inanna’s Descent” (lines

145-290)

|

|

Cuneiform

sources by line count and first appearance

|

|

Artifact color

key

|

Border key

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table

2.2. Waterfall view of cuneiform sources for “Inanna’s Descent” (lines

290-412)

|

|

Cuneiform

sources by line count and first appearance

|

|

Artifact color

key *

|

Border key

|

|

|

|

Note:

Lines 380-412 rely solely on two sources, clouding

our precise understanding of the myth’s ending.

* Artifacts f – k are not included in the line count table because they

either belong to different compositions or may have been recataloged by the

museum. Please see the full artifact page in Appendix B for more precise

information.

|

Appendix B: All

Artifact Data

Less

experienced researchers in other disciplines or members of the general public

interested in ID may have trepidation over using currently available online

resources for the purpose of artifact research and discovery. For that reason,

the following appendix provides detail pages for all cuneiform artifacts

utilized in the 2001 ETCSL version of ID. Full citations and references are

provided as well as links to online indexes of similar contents.

Basic

information about each artifact is provided: museum number, line numbers,

current location, initial publication, secondary publication(s), CDLI number,

photograph, and the autograph (where available). Artifacts are listed in the

order they appear on the tables in Appendix B and are color coded similarly to

the waterfall table for easier side-by-side comparison. Redactions and other

useful notes are listed in the foot of each table as an additional resource.

The fully listed citations are purposefully redundant so that less familiar

researchers do not have to rely on navigating between the bibliography and

appendix.

While

this appendix does not provide all the information needed for future

researchers interested in ID, it may provide a useful introductory framework

that will assist in artifact location and identification. Please note that

catalog numbers and classification information may change, so the utility of

this (and any) static resource will diminish with respect to the time of its

publication. All data are current as of April 8, 2019. Unless otherwise

noted, the high-resolution color images are derived from the corresponding CDLI

record for the artifact in question.

All

contents from the CDLI and other sources are property of their respective

owners. The fair use of third-party images and artifacts within this

unpublished undergraduate seminar research paper is asserted through its purely

educational and noncommercial nature. All other non-third-party contents have

rights reserved by the author.

|

1/A

|

CBS 12638 +

12702 + 12572 + 12684

|

|

Locate

|

|

Lines: 1-31 (obverse), 32-48 (reverse)

Location:

Penn Museum (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

|

CDLI: P267276

OMNIKA: CBS

12XXX

|

|

Publications:

Shorthand Name & Full Citation

|

Includes

|

|

|

OIP

15 or SEM 50

Chiera, Edward. Sumerian

Epics and Myths: Cuneiform Series—Volume III. The Oriental

Institute, Vol. 15. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1934. [See

plate no. 50; Available on the Oriental Institute’s website:

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oip15.pdf]

|

Line art

(sketches)

|

|

|

PAPS

85

Kramer, Samuel

N. “Sumerian Literature; A Preliminary Survey of the Oldest Literature in the

World.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 85, no. 3

(February 1942): 293-323.

|

Translation

Transliteration

Collation

Commentary

|

|

|

JCS

05

Kramer, Samuel

N. “‘Inanna's Descent to the Nether World’ Continued and Revised. Second

Part: Revised Edition of ‘Inanna's Descent to the Nether World.’" Journal

of Cuneiform Studies 5, no. 1 (1951): 1-17.

|

Translation

Transliteration

Commentary

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1/A

|

CBS 12638 + 12702 + 12572 + 12684

*

|

|

Photo

|

Line art

(sketch)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* More 12XXX

series artifacts have been added to this source and later versions of the ID

composition.

|

2/B

|

CBS 13932

|

|

Locate

|

|

Lines: 1-25 (obverse), 26-69 (reverse)

Location:

Penn Museum (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

|

CDLI: P268937

OMNIKA: CBS

13932

|

|

Publications:

Shorthand Name & Full Citation

|

Includes

|

|

|

OIP

15 or SEM 49

Chiera, Edward. Sumerian

Epics and Myths: Cuneiform Series—Volume III. The Oriental Institute,

Vol. 15. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1934. [See plate no. 49;

Available on the Oriental Institute’s website:

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oip15.pdf]

|

Line art

(sketches)

|

|

|

PAPS

85

Kramer, Samuel

N. “Sumerian Literature; A Preliminary Survey of the Oldest Literature in the

World.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 85, no. 3

(February 1942): 293-323.

|

Translation

Collation

|

|

|

JCS

05

Kramer, Samuel

N. “‘Inanna's Descent to the Nether World’ Continued and Revised. Second

Part: Revised Edition of ‘Inanna's Descent to the Nether World.’" Journal

of Cuneiform Studies 5, no. 1 (1951): 1-17.

|

Translation

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2/B

|

CBS 13932

|

|

Photo

|

Line art

(sketch)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* More 12XXX